In this insight, we outline what quantum computing is – before examining its most promising applications, expected commercialisation timelines, key technical hurdles, and the competitive landscape of the leading quantum players.

Quantum computing has moved from the realm of theoretical physics into mainstream technology discourse. Over the past few years, the sector has been making steady progress including technological milestones, increased government funding, and growing engagement from major corporations and venture capital.

We may still be decades away from fully harnessing the transformative potential of quantum computing, but progress in hardware, algorithms, and error mitigation has accelerated sufficiently to warrant serious attention from investors.

What is quantum computing?

Conventional computers – and everyday objects – operate within the laws of classical physics. Quantum computing, on the other hand, is a way of processing information that uses the laws of quantum physics. Before we dive in, however, there are three key concepts to get acquainted with:

Qubit

Qubit: A qubit, or quantum bit, is the basic unit of information in a quantum computer. A classical bit stores information as either a 0 or a 1, but a qubit can also exist in a combination of both states at the same time through a property known as superposition.

Superposition

Superposition: In classical systems, bits exist in a single, well-defined state at any given time – either 0 or 1, comparable to a light switch being either on or off. By contrast, superposition describes a quantum property whereby a system, such as an electron, can exist in multiple states simultaneously, effectively occupying both states at once.

Entanglement

Entanglement: Quantum entanglement refers to a property of quantum systems in which the state of one particle is intrinsically linked to the state of another. As a result, measuring the state of one particle immediately reveals the state of its entangled partner, even if the two particles are separated by large distances. In practical terms, entanglement allows quantum computers to process and correlate information in ways that are not possible for classical computers. While classical computers treat bits independently, entangled quantum bits (qubits) can share information instantaneously as part of a single system, which enables quantum computers to represent and evaluate a vast number of possible outcomes simultaneously, dramatically increasing computational efficiency for certain problem classes.

The outcome of superposition and entanglement, among other key tenets of quantum computing, is that quantum computers can excel at performing specific calculations in a way that is orders of magnitude more powerful than classical computers. To simplify this with an analogy, classical computing would be like checking one path at a time, whereas quantum computing would enable checking multiple paths at once, like a wave spreading over all those paths.

Why are people talking about quantum computing?

Despite their potential power, quantum computers are not expected to replace classical computers at scale. Instead, they are likely to complement systems by addressing a narrow set of problem types where quantum approaches offer a meaningful advantage. Some of the most frequently cited applications include:

Optimisation: Some real-world business problems such as routing, scheduling and supply chain management can be framed as optimisation problems, where the objective is to identify the best solution among a very large number of possible alternatives. As these problems scale in size and complexity, classical computers often rely on approximations or heuristics rather than exact solutions. Quantum computing has the potential to improve optimisation outcomes by evaluating many competing scenarios in parallel rather than sequentially.

Chemistry & Materials: Many challenges in chemistry and materials science, such as modelling molecular interactions or predicting material properties, are computationally intensive and scale poorly on classical computers. This often leads to researchers relying on approximations that limit accuracy. Quantum computing could more efficiently simulate quantum-mechanical systems at the molecular level, which could accelerate the discovery of new materials and the development of novel drugs by reducing the time and cost associated with experimentation and trial-and-error.

Finance: Financial institutions routinely rely on simulations to understand risk, price complex instruments, and evaluate portfolio behaviour under different market conditions. These exercises often involve running millions of scenarios, which can quickly become computationally expensive as models increase in sophistication. Quantum computing may offer a more efficient way to tackle certain simulation-heavy and optimisation-driven tasks, particularly in areas such as risk management and scenario analysis, where even modest gains in speed or accuracy could deliver meaningful economic value.

Cryptography: Much of today’s public-key cryptography relies on algorithms such as the Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) algorithm and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), which are widely used in applications ranging from online banking to secure messaging. A sufficiently powerful, fault-tolerant quantum computer could run Shor’s algorithm to efficiently factor large numbers and solve discrete logarithm problems, rendering RSA and ECC insecure, thus making encryption more susceptible to breaking. It is worth noting that symmetric encryption schemes, such as AES, are more resilient to quantum attacks, and the cryptographic community is actively developing and deploying post-quantum cryptographic standards to mitigate these risks.

Beyond Moore’s Law: For decades, improvements in computing performance have been driven primarily by Moore’s Law, as advances in semiconductor manufacturing have allowed more transistors to be packed onto a single chip. However, this scaling is running up against fundamental physical limits. At current trajectories, transistor features are expected to reach near-atomic dimensions within the next 10-15 years, making further miniaturisation increasingly difficult, costly, and inefficient. In this context, quantum computing is often viewed not as a direct replacement for classical systems, but as a complementary architecture that could provide continued gains in computational capability after traditional scaling has reached its limits.

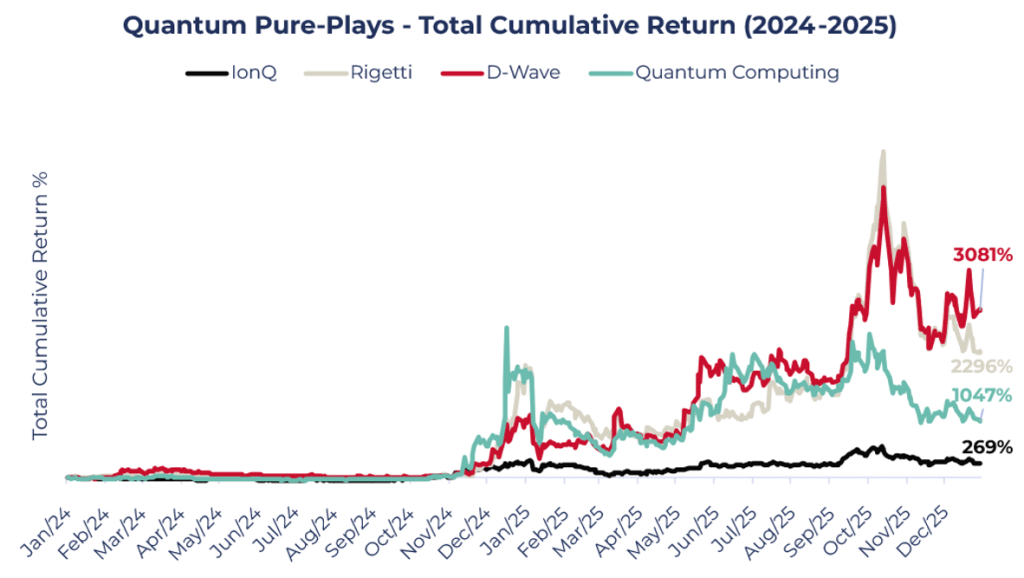

The potential of quantum computing to fundamentally reshape certain industries, alongside recent technological milestones, has fuelled investor enthusiasm for listed quantum pure-play companies.

Source: Bloomberg, Guinness Global Investors; data as of 20.01.2026

The share prices of quantum pure-plays (IonQ, Rigetti Computing, D-Wave Quantum, and Quantum Computing, shown above) skyrocketed during 2025 on technological breakthroughs and positive market commentary, taking their combined market capitalisation to $37bn (as of 20th Jan 2026) and their aggregate price to 2025E sales to 262 times despite limited revenue visibility, constant cash burn, and elevated R&D requirements. This has raised questions around market size, commercialisation timelines and technological challenges, among others.

Why should investors be interested in quantum computing?

According to Morningstar, the market size for 2024 can be estimated at $400m (including post-quantum crypto consulting). As experimentation continues and the technology evolves, experts predict solid growth until 2029, but after that, an inflection until the mid-2030s with market revenue potentially hitting $20bn a year. Timelines around market growth span a wide range of outcomes, as demonstrated by Rigetti’s estimate of $15-$30bn in annual revenue during the 2030 to 2040 timeframe. Looking over the longer term, Morningstar estimates a base-case market size of around $200bn at maturity, achieved over a roughly 30-year timeframe. Importantly, the distribution of outcomes is fat-tailed, as illustrated in the chart below, illustrating the uncertainty surrounding a technology that is still many years away.

Source: Morningstar, Guinness Global Investors, 2025

Given the current state of the quantum ecosystem, hardware, software and the technology itself, early commercialisation seems to be at least five to ten years away. Historically, the time gap between early advancements and commercial deployment has been large, with ASML serving as a prime example. The firm started its EUV (Extreme Ultraviolet) programme in 1997, but didn’t deliver its first production unit until 2017. This experience highlights both the technical complexity of bringing new computing technologies to market and the challenge of building a fully functional ecosystem around them.

What challenges does quantum computing face?

One of the main challenges slowing the development of quantum computing is decoherence, which causes qubits to lose their quantum state through interaction with their environment. This limits how long quantum information can be preserved and constrains the depth and reliability of quantum computations.

In addition to decoherence, quantum systems are affected by gate and readout errors, which arise when quantum operations are executed imperfectly. These errors accumulate rapidly as computations scale, limiting the depth of quantum circuits that can be reliably run. In fact, IBM recently revised down its quantum computing roadmap, significantly reducing the number of qubits expected to be achieved over the next few years, as they observed a larger number of errors when increasing the number of qubits. Addressing this requires quantum error correction, a process that significantly increases hardware complexity by requiring many physical bits to encode a single logical qubit, thereby raising both engineering challenges and system costs.

Quantum computing development requires large capital spending

Despite the challenges laid out above, the technology is evolving fast and both governments and private investors are allocating growing amounts of capital to get ahead in the quantum race.

According to Qureca, worldwide government investment (or announced investment) into quantum computing rose to $55.7bn during 2025. As the image below shows, China allocated the most, followed by Japan and the United States.

Investor enthusiasm has also been growing on the venture capital side. 2025 saw the largest amount of private capital ever invested into quantum computing, totalling $3bn. At the same time, it is likely that generative AI has been crowding out investment in quantum computing and other advanced technologies over the last three years. We analyse the huge AI spending and its implications here.

What benefits do quantum computers bring for users?

Today, quantum computers remain inferior to classical computers across most practical dimensions, including performance, reliability, scalability, and cost. Classical computing benefits from decades of engineering optimisation, built-in error correction, mature software ecosystems, and cloud-scale deployment, making it the dominant solution for virtually all general-purpose workloads.

By contrast, current quantum computers are slow, error-prone, expensive, and largely experimental, limiting their usefulness to narrowly defined research and proof-of-concept applications.

Over the longer term, however, this balance could shift for specific classes of problems. In a fault-tolerant era, where quantum error correction is successfully implemented and systems can scale to large numbers of high-quality logical qubits, quantum computers are expected to outperform classical machines on tasks characterised by high complexity, combinatorial explosion or inherently quantum behaviour.

Importantly, this advantage is likely to be domain-specific rather than universal: classical computers are expected to remain superior for general-purpose computing, while quantum systems could become the preferred tool for a subset of computationally intensive workloads.

As a result, the long-term opportunity for quantum computing should be viewed as complementary rather than substitutive. Rather than replacing classical infrastructure, quantum computers are more likely to augment existing computing stacks, accessed primarily through the cloud and integrated into hybrid quantum-classical workflows once technical and economic hurdles are overcome.

Who is investing in quantum computing and is it available for public use?

When assessing the quantum landscape in the stock market, we can divide in two groups: Public Cloud Providers & IBM, and the pure-plays. The first group encompasses Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, and IBM, all of which have strong balance sheets, long-standing R&D programmes, early-stage quantum platforms and near-zero quantum revenue built into consensus estimates on which they are valued in the market.

The pure-plays (IonQ, D-Wave, Quantum Computing, Rigetti), on the contrary, are burning through cash, have limited R&D resources and are likely to need capital infusions. Their valuations reflect highly optimistic quantum computing revenues in the not-so-distant future.

Source: Guinness Global Investors, January 2026

IBM

In the case of IBM particularly, this has been more noticeable as the number of SDK downloads have more than doubled from October to November 2025, as seen in the chart below.

Interest in Quantum SDKs is Growing

This early lead largely reflects IBM’s early progress in productising its quantum computing capabilities. Even more importantly perhaps is the growing ecosystem that the major cloud providers are developing well in advance of the quantum computers even getting to the early-adopter phase.

Public Cloud Providers

Microsoft and Amazon (both held in our Guinness Global Innovators Fund) offer cloud services (Azure Quantum and Amazon Braket) that enable customers to access quantum hardware from selected pure-play providers.

We would expect these companies, alongside Alphabet (also held in the Guinness Global Innovators Fund), to continue expanding and integrating their quantum computing capabilities within their broader cloud platforms.

Nvidia

We also highlight Nvidia (another holding in the Guinness Global Innovators Fund), whose CUDA-Q platform enables developers to build and run hybrid quantum-classical applications on accelerated computing systems, positioning the company as a key enabler of quantum workflows rather than a direct quantum hardware provider.

Source: Morningstar, Guinness Global Investors, January 2026

How can investors get exposure to quantum computing?

There is no clear, uniform path toward quantum computing. Instead, the industry is characterised by multiple competing technological approaches, reflecting both the early stage of development and the lack of consensus around an optimal architecture.

In this environment, strong balance sheets and the ability to build and sustain a broader quantum ecosystem, including hardware, software, and research capabilities, are emerging as key prerequisites for companies seeking to lead in the quantum race.

The major public cloud providers: Microsoft, Alphabet and Amazon are therefore well positioned in the quantum race, and given their valuation levels, they offer an attractive long-term play on quantum computing.

The Guinness Global Innovators Fund currently holds many of the central players in the early quantum computing space. With a rigorous approach to quality and long-term returns, the Fund is geared to benefit from rising investor interest as new innovations and technologies advance quantum computing from theoretical proof-of-concept to real-world applications. Learn more about the fund and its holdings here.

Risk: The Guinness Global Innovators Fund and WS Guinness Global Innovators Fund are equity funds. Investors should be willing and able to assume the risks of equity investing. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency movement; you may not get back the amount originally invested. The Funds are actively managed with the MSCI World Index used as a comparator benchmark only.

Disclaimer: This Insight may provide information about Fund portfolios, including recent activity and performance and may contains facts relating to equity markets and our own interpretation. Any investment decision should take account of the subjectivity of the comments contained in the report. This Insight is provided for information only and all the information contained in it is believed to be reliable but may be inaccurate or incomplete; any opinions stated are honestly held at the time of writing but are not guaranteed. The contents of this Insight should not therefore be relied upon. It should not be taken as a recommendation to make an investment in the Funds or to buy or sell individual securities, nor does it constitute an offer for sale.