Markets can reprice JGBs overnight, but the real fault line between volatility and vulnerability is when the effective interest rate surpasses growth

Japan’s ultra-long-bond sell-off has been dramatic enough to revive an old question: could Japan’s debt eventually become unsustainable? Since Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi took office in October 2025, investors have had to price in a more expansionary fiscal stance. The repricing accelerated when she called a snap election for February 8, 2026, alongside talks about further tax-relief measures, resulting in the latest yield shock. The 40-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yield ascended above 4% and the 30-year rose by roughly a quarter point in a single session,[1] a pace that would have been almost unthinkable during the era of yield-curve control. Japan’s government debt is still around 230% of gross domestic product (GDP),[2] so it is understandable, in our view, that markets react nervously when the term premium moves into focus – at least temporarily.

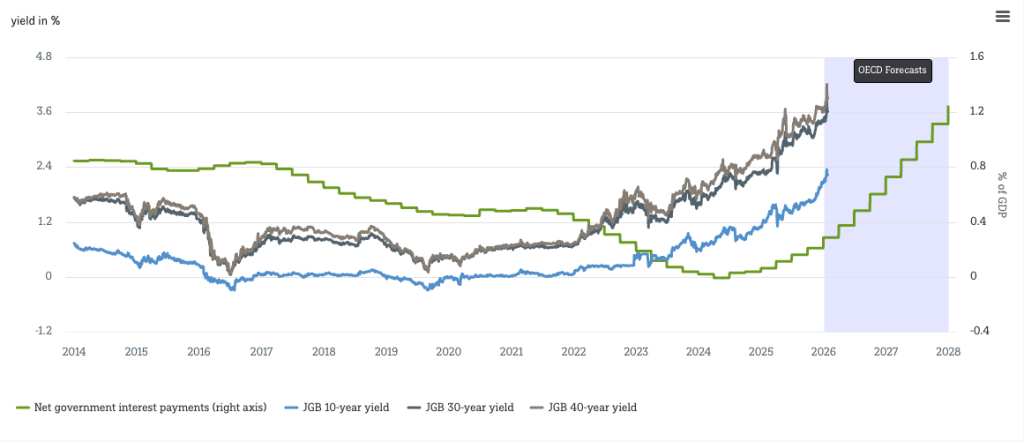

Our Chart of the Week helps translate that market drama into debt arithmetic. The left axis tracks 10-year, 30-year and 40-year JGB yields, capturing how the long end has repriced sharply and has become more volatile. But the crucial bridge to debt sustainability is shown on the right-hand axis: net government interest payments as a share of GDP, where the blue shaded area marks the forecast period through end‑2027 by the organization for economic co-operation and development (OECD). Even with yields having moved materially higher, the chart implies that the interest burden rises only gradually and with a lag. In other words, Japan’s sovereign financing cost is a stock story, not a spot story: the average interest bill adjusts with long lags as the existing low‑coupon debt stock rolls over – which is why the interest expense still shows inertia.

This is where the debt sustainability debate should lose its drama: A country’s debt pile is considered sustainable, as long as nominal growth stays above the effective interest rate on the outstanding debt stock (assuming that the primary budget remains balanced). That logic is consistent with external assessments, too: The rating agency Fitch notes that reflation can support near‑term debt dynamics because the effective interest rate rises only gradually and has remained below inflation, even as yields normalize.[3]“Japan’s debt dynamics were quite well in recent years. Due to the return of inflation and thus higher nominal growth, the debt-to-GDP ratio has already entered a declining path. Given our positive outlook for both real growth and inflation, Japan’s fiscal position also seems stable,” points out Lucas Brauner, Japan Economist at DWS.

Brauner further adds that the risk case is the mirror image: “If inflation were to slip decisively while interest rates remained elevated, nominal growth might no longer exceed effective interest rates, ultimately leading to a higher and potentially unsustainable debt-to-GDP ratio.” Uncertainty around the extent of the fiscal expansion is another risk factor. Japan’s bond market may stay volatile for a while, but the sustainability arithmetic still hinges on growth and inflation, not solely on the yields of long / ultra-long Japanese government bonds.

This information is subject to change at any time, based upon economic, market and other considerations and should not be construed as a recommendation. DWS does not intend to promote a particular outcome to the Japanese election due to take place in February 2026. Readers should, of course, vote in the election as they personally see fit. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. Forecasts are based on assumptions, estimates, opinions and hypothetical models that may prove to be incorrect. Alternative investments may be speculative and involve significant risks including illiquidity, heightened potential for loss and lack of transparency. Alternatives are not suitable for all clients.