When seeking opportunities in China, equity investors must understand the importance of the alignment between corporate and central government priorities, Emerging Market Equity Portfolio Manager Daniel Graña explains.

Key Takeaways

- China’s central government has established a new set of national priorities with the aim of increasing economic self-reliance and sophistication while also furthering the objective of “common prosperity.”

- Corporate strategies are expected to be aligned with these priorities, and failure to do so increases the risk of regulatory scrutiny.

- When selecting securities in China’s equities market, investors should rely upon both fundamental company analysis and – increasingly – a “political governance” lens.

The phrase “the only constant is change” may not have been coined by investors, but it’s an idea they should take to heart given the dynamism of both the global economy and financial markets. It applies to individual asset classes as well, and one notable development is how much emerging market (EM) equities have evolved in the years since China became a major actor in the world economy and destination for investment capital. The obvious benefit of China’s ascendancy has been the steady stream of attractive investment returns. In the 20 years ended December 31, 2021, the country’s economy, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), grew at an annual rate of 8.7% and its equity market generated annual returns of 11.2% in U.S. dollar terms, based on the MSCI China Index. The downside is that Chinese stocks now account for roughly 32% of the MSCI Emerging Markets® Index, which not only gives it tremendous sway over the entire asset class, but also – given the country’s particular economic and political structure – poses a host of considerations that merit investors’ attention.

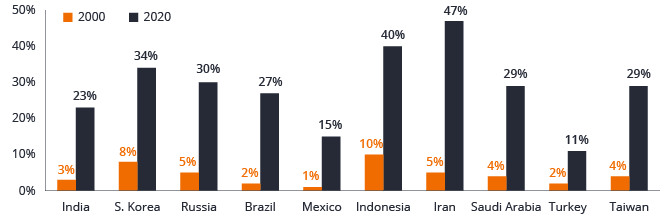

Exhibit 1: MSCI EM Index Composition by Country

China constitutes nearly a third of the emerging market equities benchmark, and its share would climb toward 50% should Mainland (A) shares be fully included.

These questions have grown in importance in recent years as the central government has taken a more assertive stance in managing the country’s economic affairs and its sometimes freewheeling private sector. While demographic shifts likely mean the period of China’s most rapid growth is in the past, the potential for attractive returns remains. Accessing them, however, has grown more complicated. Unlike in developed markets, equity investors cannot focus on company-specific drivers to the exclusion of system-wide factors. The “macro,” in our view, has always mattered in emerging markets, but with the ever-larger role played by political governance in influencing China’s economic and market outcomes, investors must be cognizant that the playbook that worked for emerging market equities over the past few decades no longer applies in the Asian giant.

A New Chapter for the Playbook

Since their progression into a formidable asset class, EM equities have generated returns for investors on the back of two durable secular themes:

- The outsourcing of the world’s manufacturing capacity to EM countries as multinational corporations attempted to harness the efficiencies of globalization. In this sense, EM equities acted as a “call option” on global GDP growth.

- The convergence of income and living standards between EMs and developed markets as the former’s workforces gained productivity-enhancing skills that enabled their home countries to move up the value chain and increase national wealth.

Implicit in each of these was EM countries largely emulating more advanced economies by privatizing industries, increasing cross-border trade and creating the regulatory and legal framework that allow a private sector to thrive. While these themes still have room to run in many instances, the rise of China’s economic might has enabled the country to define its own rules of the road on the path toward upper-income status. These rules – from how laws governing the private sector are created to how they are applied – are alien not only to developed market investors, but also to many who have ridden the sometimes volatile, but relatively templated, wave of EM growth over the past two-plus decades.

That China plays by its own set of rules was brought home by a series of developments over the past 18 months. The high-profile initial public offering of ANT Financial was canceled at the eleventh hour; ride-sharing company Didi had to delist from the New York Stock Exchange under the auspices of data security; and the education industry saw billions of dollars in market capitalization erased, also on grounds putatively related to security, and the increasingly publicized maxim of “common prosperity.”

Is China Still Investable?

The degree to which the playing field has changed – and the incremental level of risk it entails – bodes the question: Is China still investable? The answer is yes, but it comes with a notable caveat. Analyzing the competitive position and earnings potential of individual companies is not enough. Perhaps more than in any other country, understanding increasingly assertive political governance is equally necessary in assessing the risk profile of a particular company or industry.

Unlike Western systems of government where rule of law is the guiding principle, China is guided by rule of party. There is no open deliberative process, no independent institutions applying checks and balances nor elections providing feedback from citizens. And while the private sector has been given relatively free rein during the years of economic liberalization, the party has now let it be known that the economy is just a tool in meeting certain state objectives rather than a system in and of itself.

Resetting National Priorities

The no-holds-barred industrialization and urbanization that China rode toward becoming a middle-income country are behind it. The central government has defined a new set of national priorities that it expects to propel the next stage of economic development while also addressing acute social, economic and even geopolitical exigencies. In recent years, these objectives have become prominently featured in officials’ speeches, party directives and regulatory rulings. While the central government still maintains other priorities, the three that we expect to have the greatest influence on policy over the mid-term are:

- Innovation: China has long sought to move up the value-added chain. The growth of more advanced processes and products would not only boost productivity and incomes, but also provide a domestic alternative to many technologies and goods that presently can only be sourced abroad. The U.S.-China trade war exposed these vulnerabilities, and by prioritizing domestic innovation, the country would move toward its “dual circulation” objective where it still participates in the global economy in some areas but also becomes self-sustaining in other key industries.

- Decarbonization: While China likely shares the concerns of other countries about the environmental impact of continued reliance on hydrocarbons for energy needs, it has the added incentive to secure its energy resources. A yawning gap exists between China’s demand for oil and domestic supplies. In the eyes of Beijing, this represents a strategic vulnerability that must be remedied. Furthermore, the country already enjoys a commanding position in the renewable energy supply chain. Continued emphasis on renewables not only achieves the objective of energy independence, but also can further cement China’s global leadership in a high-value, growth area of the global economy.

- Common Prosperity: In harkening back to its roots, the Communist Party of China has recently taken steps to rein in what it sees as the excesses of capitalism at the expense of the greater good. Specifically, the party wants to mitigate highly bifurcated economic outcomes for its citizens before inequality becomes entrenched. While the government continues to recognize the valuable role played by the private sector, it doubts that market outcomes alone can achieve common prosperity. Fueling profit margins by exploiting gig workers no longer cuts it. And by gaining regulatory control over emerging strategic industries, such as fintech, it can ensure that the ethos of common prosperity is embedded in these business models.

None of these priorities are anathema to a healthy private sector or Chinese equities continuing to be an attractive destination for global investors. They do, however, lay out the rules of the road to which investors should adhere. Due diligence of Chinese companies can no longer stop at analyzing end markets, management teams and profitability; it must also include whether business models adhere to state priorities. Companies that are aligned with government objectives can likely continue to deliver value to shareholders as long as they stay within these defined parameters. In contrast, those that haven’t gotten the message are putting themselves at risk of being on the receiving end of the sometimes harsh regulatory scrutiny that authorities have wielded over the past several quarters.

“The” Driver in Emerging Markets

With investors now having to navigate factors such as political governance that are typically beyond the purview of equities analysis, some may ask whether the risk of China exposure is worth it? Despite the shifting landscape, we believe the real risk is avoiding Chinese stocks. As illustrated in Exhibit 1, Chinese companies already comprise roughly one third of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, and that is with Mainland listings only partially included. Should these “A Shares” be fully included, China’s representation in this benchmark would climb to approximately 50%.

This sizing is not arbitrary. China is the dominant emerging market and the second-largest economy in the world. Furthermore, many of the key themes that attract investors to the asset class are most pronounced in the country. A zero weight to the Asian giant would remove not just a significant portion of the investable universe from consideration, but also limit access to powerful themes such as rising consumption, the digitization of the economy and innovation across a host of value-added industries.

Increasingly, the fate of other emerging countries is tied to China. As illustrated in Exhibit 2, the country is a major buyer of commodities from EM natural resource producers and of components destined for its immense manufacturing base.

Exhibit 2: Emerging Market Exports to China as a Percentage of All Exports

As China’s economy continues to transition toward consumption, a larger amount of these imports will remain in the country rather than continue onto developed markets in the form of finished products. Goods and services flow the other way as well, exemplified by Chinese gaming, social and fintech platforms expanding their footprint in other emerging markets.

The pace at which EM companies are trading – and competing – with each other is rising. In order to properly assess the competitive landscape and identify the most promising investment opportunities, we believe one should take a holistic view of EM equities. With their fortunes so intertwined, we believe the notion that China equities should be viewed as a separate asset class from other EM equities sells short the magnitude of this relationship and, thus, would introduce inefficiencies into the investment process.

Another development that should further raise China’s relevance to EM investors in the establishment of a dual-circulation economy. This initiative seeks to increase China’s level of economic self-sufficiency in strategic industries while also keeping the country enmeshed in the global trading system. The government’s objective is to reduce its dependence on imports of key inputs, ranging from semiconductors to energy. The “internal” segment of the economy will help further strategic priorities and cater to rising domestic consumption. It will also likely be the domain of more complex, value-added processes that both the government and investors would favor. In contrast, while there are exceptions and additional efficiencies to be reaped, the “external” sector would likely rely upon lower-margin manufacturing processes.

An Innovative Future

Complementary to economic self-reliance and value-added industries is innovation. Historically investors have sought exposure to novel technologies and processes via developed markets. In recent years, EMs have become a source of innovation in their own right. Importantly, new technologies and business models are aimed at addressing unique business frictions within EMs. In finance, fintech companies are enabling large, unbanked populations to access the financial system, and blockchain applications have the potential to provide credit solutions for small businesses. Similar developments are occurring within health care and – in the case of e-commerce and food delivery – the consumer sector.

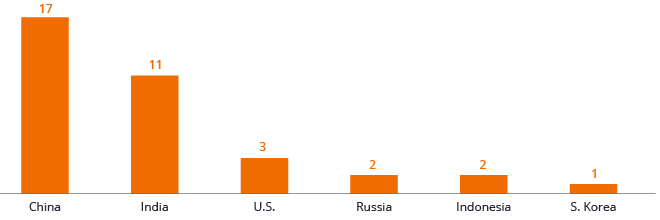

As shown in Exhibit 3, with its large population of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) students and Internet users, China is well positioned to enhance productivity within industries and compete globally across a range of sectors in coming years. Innovation has become a dominant secular theme across all geographies, and research-driven Chinese companies will likely need to be a central component of EM allocations seeking exposure to these disruptive forces.

Exhibit 3: University Enrollment in STEM Curricula (Ms)

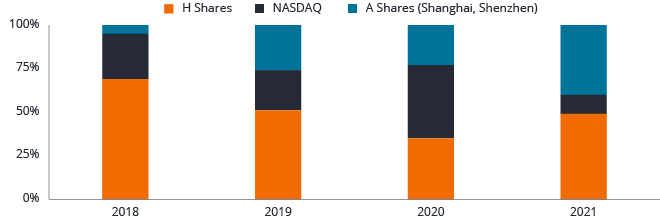

How investors access innovation in China is changing too. Many new offerings are likely to be steered toward Hong Kong’s exchange for Mainland companies (H Shares) while established ones may feel the need to make Hong Kong their primary exchange. This process is already underway (as seen in Exhibit 4) as the share of Chinese companies listed in Hong Kong has risen at the expense of the NASDAQ.

Exhibit 4: China Exposure within the MSCI Emerging Market Index

While these developments may provide a boost to Hong Kong’s equities exchange, companies listed on the Mainland (A Shares) should also benefit from the government’s emphasis on common prosperity and innovation. Implicit in a domestic listing is more robust government oversight and lower concerns about the reach of foreign securities regulators. Mainland exchanges are also home to many innovative technology and biotech companies. This stands in contrast to Hong Kong, which hosts many state-owned enterprises in banking, communications and energy that were popular with an earlier era of China equities investing.

Balancing Promising Opportunities and Unique Risks

In summary, China cannot be ignored by investors. The size of the economy and progress of its innovative businesses are proof of that. But the rules have changed, and the central government – by delineating its strategic objectives – has laid out how companies are expected to function in this unique economic system. As new and disruptive businesses grow and become more sophisticated, the traditional skills of fundamental company analysis and security selection will be important tools in identifying the most promising opportunities. Yet, investors cannot rely exclusively on a company-centric lens. Governance and country-level, macro drivers will also play a role in effectively navigating this distinctive landscape. Political risks have undoubtedly risen, but we expect that both the private economy and international investor capital are welcomed as long as these entities’ objectives are aligned with those of the party. Not only does experience matter in determining the nexus between state and investor priorities, so does the recognition that China’s multi-decade – and likely continuing – rise has created a more complex environment for EM investors to navigate.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. Any securities, funds, sectors and indices mentioned within this article do not constitute or form part of any offer or solicitation to buy or sell them.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.