Portfolio Managers Jason England and Daniel Siluk explain how the interest rate risk embedded in market cap-weighted fixed income benchmarks left investors acutely exposed during this year’s bond selloff.

Key takeaways

- The expected benefits of portfolio diversification have eluded investors this year as policy tightening sent prices of both bonds and riskier assets lower.

- As fixed income indices reflected the considerable duration risk present in the aggregate bond market, strategies that closely track these benchmarks were acutely exposed to rising interest rates.

- With market inefficiencies – and risks – still present, bond investors should consider strategies that provide greater latitude in managing duration risk and adjusting exposure between government issuance and corporate credits.

This year has been a sea of red for traditional asset classes. Within equities, many benchmarks have fallen by as much as 20%. Government bonds have also sold off, with yields rising in some cases by more than 200 basis points (bps) above their 2020 lows, with most of the damage occurring in 2022. Corporate bonds have suffered as well, and property prices are starting to fall in some areas. Even less traditional asset classes such as cryptocurrencies have not been immune, with many experiencing dramatic selloffs. Only commodities seem to have weathered these currents, rising under a perfect storm of pandemic-related supply-side constraints and geopolitical events such as the invasion of Ukraine.

When tides shift, water usually flows from areas of low tide to areas of high tide, with the water level rising in one region at the same time it recedes elsewhere. Financial markets can display a similar phenomenon. At times of heightened fear, investors shift toward defensive asset classes such as bonds while shying away from riskier assets such as equities. The converse tends to occur when times are good: Higher earnings expectations boost the demand for equities, while bonds sell off as rates move upward. The result is often the price of risky and defensive assets moving in opposite directions.

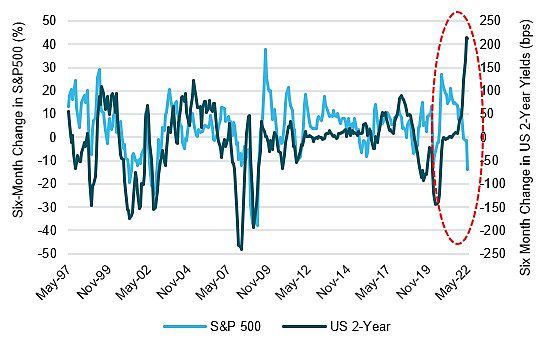

One way to show the usual historical correlation between bonds and equities is to look at the six-month change in both the S&P 500® Index and yields on the 2-year U.S. Treasury note. The chart below shows that the two normally move together. That said, periods where bond yields and equities diverge are not uncommon. For example, leading into the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), bond yields fell significantly as the Federal Reserve (Fed) started cutting rates but equities continued to rally. However, these periods don’t tend to last for long before the historical relationship reasserts itself.

Six-month change in S&P 500 and US 2-year yields

What is so unusual about this year’s price action is that returns of risky and defensive asset classes have moved significantly down together. Short-term U.S. Treasury rates have risen by more than 200 bps in the past six months – a pace unparalleled in the past 25 years. Equities’ slide has been significant but not quite as extreme in relative terms. The roughly 20% fall from the peak in the S&P 500 puts it in the second tier of risk-off episodes, still some distance from the 35-60% selloffs seen during the GFC or at the start of the pandemic. Nonetheless, it is the fact that these occurred at the same time that is relatively unusual. For example, April represented only the fourth month in almost 50 years that equities and bonds both fell substantially.1

So what caused the “tide that lifts all boats” to subside so suddenly? We see it as largely due to the unwinding of the emergency stimulus introduced at the start of the pandemic. Rates cuts and asset purchase programs have not just stopped but are now being unwound. The significant boost from fiscal policy is also fading. Both of these processes have been hastened as labor markets have recovered much more quickly than in previous recessions. This has resulted in higher and non-transitory inflation becoming a dominant concern. The expansion of money in the system due to cheap borrowing costs and central bank purchases is now starting to flow out of the system. The tide is receding, and just as it did when it rose, it’s impacting the price of many asset classes simultaneously.

Implications for investors

Asset allocation based on the historical correlations between risky and defensive assets has unsurprisingly performed poorly. Risk parity-style approaches to portfolio construction such as the 60/40 split between equities and bonds have registered steep losses. It’s perhaps not surprising that when positive correlations between risky and defensive assets resulted in higher returns, investors did not pay as close attention as when asset prices turned south.

Fixed income is no exception, with traditional benchmark-aware funds not faring well. Benchmark bond indices recorded declines that investors typically only see within allocations – a development all the more painful as it occurred at a time when equities themselves were falling.

One factor in fixed income indices’ recent declines is their composition being based solely on the amount of bonds available. There is no efficiency or capital preservation underpinnings in the construction of these benchmarks. In our view, this is important given the degree to which aggregate bond market duration has lengthened over the past several years. By definition, longer duration significantly increases the interest-rate sensitivity of bonds. This matters – a lot – given the inevitable rate-tightening cycle that is now underway. We believe it is extremely difficult for active decision making within benchmark-linked bond strategies to offset the large, rate-driven declines the market has experienced recently.

Rather than accept elevated duration risks embedded in fixed income benchmarks as constructed, we believe investors should expand their universe by considering securities that still present the characteristics they’ve come to expect from their bond allocation. Increasingly, this means favoring corporate bonds over government issuance. And while investment-grade corporates offer incrementally higher yields than government bonds, they still have considerable sensitivity to interest rates. This is evidenced by early-year losses in the investment-grade segment of the market. With this in mind, however, investment managers can take steps to hedge corporates’ interest-rate risk, thereby maximizing exposure to these securities’ credit risk premium, which has risen over the course of 2022.

In this context, this year’s tumultuous investment environment highlights the importance of focusing on absolute – not relative – return. By identifying the acute risks present in fixed-income benchmarks and taking steps to actively limit exposure to them, investors can maximize the characteristics they expect from their bond allocation while dampening the ill effects of worryingly high duration risk.

Concluding thoughts

Warren Buffet’s famous quote, “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked,” has never been more apt. The turbulence of 2022 has revealed which investment philosophies have unduly relied on historical correlations as well as those based solely on maximizing exposure to the highest-returning – and riskiest – securities. While some losses have proven unavoidable for most bond strategies, in 2022 we are reminded that the best offense is often a good defense – and that defense in this instance means making great efforts to get out of the way of the interest rate tidal wave inundating aggregate benchmarks.

To finish on a positive note, the challenges faced this year also present an opportunity looking forward. Rising rates are not necessarily a bad development. For over a decade, we’ve all moaned about astonishingly low bond yields. Important at this juncture is the pace of yield rises, which will dictate the trajectory of bond returns. Barring any short-term surprise, investors have the opportunity to reinvest maturing securities at yields higher than what had been available only weeks or months prior. This strategy is all the more relevant for approaches biased to shorter-dated assets that can exit highly liquid positions and reallocate toward longer-dated, higher-yielding securities of similar quality. If inflation proves more persistent than expected but policy rates remain on hold, shorter-dated strategies and/or those with active mitigation of duration sensitivity are also likely to be less impacted by rising rates than those with extended duration profiles.

The higher yields now present in the market provide a higher level of coupon income than what existed only a few months ago and can act as a buffer to additional market weakness. The potential return of the usual negative correlation between rates and riskier segments of the market has the potential to make fixed income allocations more relevant than they have been in the past several years. We expect that this negative correlation will return once peak inflation and peak hawkishness from central banks subsides. Indeed, one could argue that we are already at that point. Regardless, it will remain vital for investors to learn how to survive in shallower water and, more importantly, to be prepared for unexpected changes in tide.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Equity securities are subject to risks including market risk. Returns will fluctuate in response to issuer, political and economic developments.

Diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing investment losses.

Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Correlation measures the degree to which two variables move in relation to each other. A value of 1.0 implies movement in parallel, -1.0 implies movement in opposite directions, and 0.0 implies no relationship.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

S&P 500® Index reflects U.S. large-cap equity performance and represents broad U.S. equity market performance.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. Any securities, funds, sectors and indices mentioned within this article do not constitute or form part of any offer or solicitation to buy or sell them.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.