Key Takeaways

Strong demand for crude oil as economies rebound from COVID has pushed oil inventories to the lowest levels in a decade.

Chronic underinvestment in production capacity has constrained the global oil supply.

Because the supply/demand disconnect will not be resolved quickly, we expect high and volatile energy prices for many years.

There's More to Energy Price Volatility than the War in Ukraine

Global energy markets have experienced remarkable volatility over the past two years. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil famously printed a negative price in May 2020 during the depths of COVID lockdowns. But earlier this year, in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, crude jumped to around $130 per barrel, reflecting a ‘war premium’ and fears of Russian supply losses.

Since then, prices have moderated. Countries have taken steps to mitigate the production shortfall, and the war and sanctions have not disrupted the Russian supply as much as initially feared.

While the oil market has avoided the worst-case scenario in the near term, we believe secularly tight oil markets and high volatility are the most probable outcomes over the next decade. We think energy market participants may not yet appreciate these long-term, structural supply and demand imbalances.

Supply was Tight Entering 2022

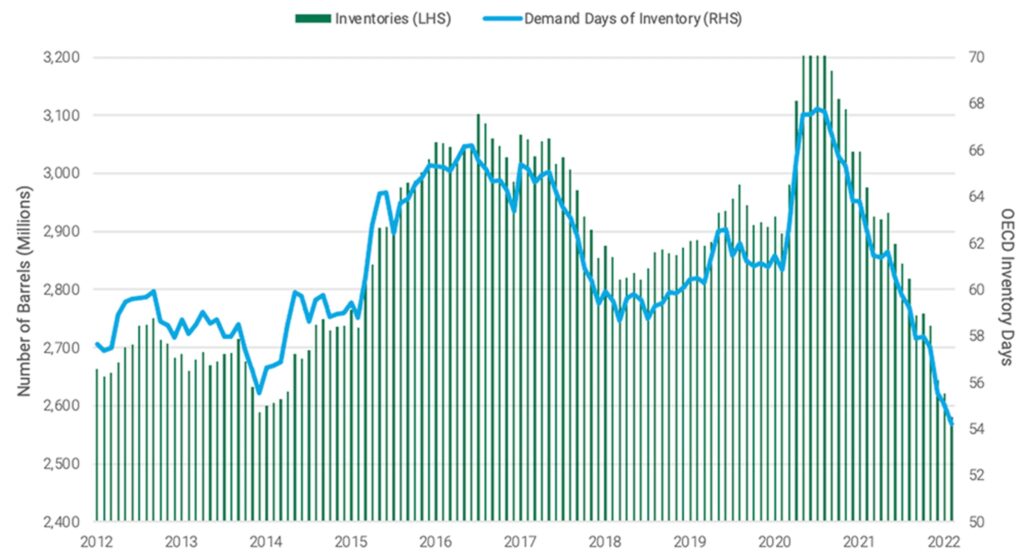

Oil markets were in a precarious position even before Russia invaded Ukraine. Commercial inventories—the best real-time metric of readily available oil—have been plumbing decade-long lows on both an absolute and days-of-demand basis. These conditions reflect an exceptionally tight market where demand outstrips supply and depletes excess inventory as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 | Inventories Touch the Lowest Level in a Decade

Global demand for transportation fuel—particularly for jets and commercial transportation—has experienced a strong rebound. Furthermore, demand for refined oil products was much-stronger-than-normal during the winter of 2021–22 due to Russia’s limitations on natural gas sales to Europe in advance of its Ukraine invasion. We would typically expect a seasonal respite in demand during the winter months.

On the supply side, we have experienced a significant shift from the pre-pandemic environment of rapid growth in U.S. shale output and plenty of spare capacity from members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Today, opportunities for supply growth are more limited.

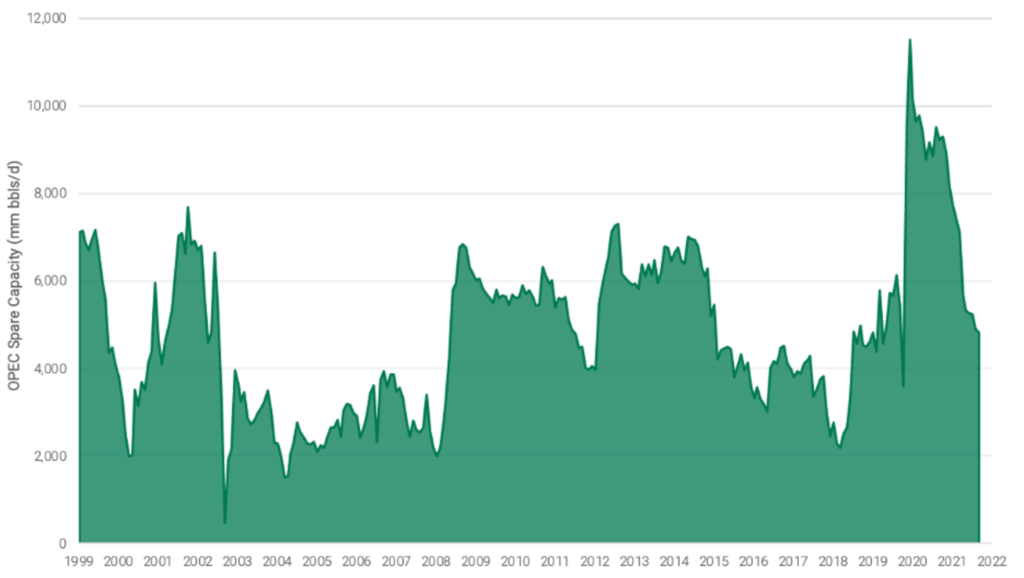

OPEC has been bringing back its capacity over the past two years to meet demand and is getting closer to its fundamental supply limits. The cartel reports that its spare capacity is approximately five million barrels per day. But in our view, the actual level they could quickly bring online is closer to three million barrels per day. For perspective, that’s roughly the same level of spare capacity that persisted from 2003 to 2007, a period of strong oil prices (see Figure 2).

Meanwhile, the large, publicly listed North American upstream energy companies (those involved in oil extraction and production) are under shareholder pressure to limit their future supply growth. Investors are demanding management teams generate free cash flow and higher returns on capital. They’re also reluctant to invest new capital in hydrocarbon projects when the long-term trend is toward decarbonization.

Shareholders and corporate management also have been reluctant to make significant capital investments because of the risk that these longer-dated projects could become ‘stranded assets’ in the future, given evolving environmental regulations and concerns.

Figure 2 | OPEC Spare Production Capacity Tumbling

The upshot is that the global oil market finds itself in a difficult position after years of U.S. shale output fueling abundant supply growth. U.S. supply growth is slowing, OPEC’s spare capacity is limited and demand remains strong, even if that absolute demand level may be quite different in 20 years.

Sanctions on Russia Further Threaten Supply

The sanctions resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine create the possibility of additional supply shortfalls. Some countries have directly sanctioned Russian oil imports. Meanwhile, other financial sanctions and self-sanctioning by Western companies may limit Russia’s ability to deliver its five million barrels per day of seaborne crude. Hurdles include difficulty gaining tanker access/insurance and firms abandoning projects because of reputational risks.

Even though we have seen increased uptake from Indian and Chinese buyers, a pending European Union ban on Russian oil will lead to a significant decline in demand from European buyers. That’s significant because continental Europe historically has been the dominant purchaser of Russian energy resources.

While the conflict is now several months old, we are only just beginning to see the physical market impacts, given the time involved in global physical oil tanker transit and the gradual evolution of the sanctions regime. There is a potential risk of losing Russian export barrels that cannot be made up by further releases from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Longer term, the heavy sanctions, particularly those related to the innovation that western oil companies brought into Russia, are likely to lead to a persistent production decline from the world’s second-largest oil producer. We think the effects would be similar to the impacts we’ve seen in Venezuela and Iran, which have experienced comparable sanctions. Another potential model could be the effects we saw in Russia in the early 1990s after the economic chaos that resulted from the end of the Soviet Union and the transition to a capitalist economy.

Demand Dynamics are Shifting

Meanwhile, global secular demand for oil and refined products continues to grow, albeit slower than in years past. We believe rising demand from emerging markets economies and for ocean freight and air transportation will likely ensure oil demand growth for an additional 15-20 years.

In contrast, developed market economies have begun to reduce consumption because of a slow but steady transition from gas to passenger electric vehicles. In the very short term, the slowing global economy and continuing lockdowns in China are additional risks to demand.

Expect Higher, More Volatile Prices as We Reach the End of Hydrocarbons

We find ourselves in a paradoxical situation. From one perspective, we have a line of sight to an eventual end of the oil age—the switch over of the passenger vehicle fleet to electric vehicles and the eventual development of lower-carbon options for other sources of oil demand.

However, the very fact that we can see this end somewhere over the horizon leads us to believe we are set for a period of secularly tight markets, resulting in high and volatile oil prices. With demand likely to peak within the next two decades—and continuing shareholder demands for capital returns—companies are increasingly unwilling to invest in new oil production.

At the same time, the traditional release valve of OPEC is beginning to be tapped out. The developed nations’ strategic petroleum reserves have been utilized multiple times and will be approximately 50% depleted this year. And still, demand is growing. Though the growth rate is modest, it’s exerting upward pressure on prices. Therefore, without a willingness to invest in long-lived supply, the potential upside for oil prices becomes significantly unbounded.

Add it all up, and relatively high and highly volatile oil prices are likely for the remainder of the 2020s.