The cycle and the spreads: 23 August 2022

- The UK – the land where a soft landing is not even considered

- Unease in China looks deeper than most thought

- European HY – the duration, the spread, and the recession

The UK’s textbook stagflation

UK inflation climbed in July: headline inflation increased from 9.4% in June to 10.1% in July, while core inflation expanded from 5.8% to 6.2%. The headline figure was driven by sharp rises in food price inflation combined with soaring energy prices, deepening the cost-of-living crisis in the UK. This worsening trend for consumer purchasing power is also clearly reflected in deteriorating consumer confidence numbers, as they reached a historic low of -44 in August.

On a positive note, UK retail sales excluding auto and fuel rose more than expected by 0.4% in July from the previous month. The market had expected a 0.3% decrease.

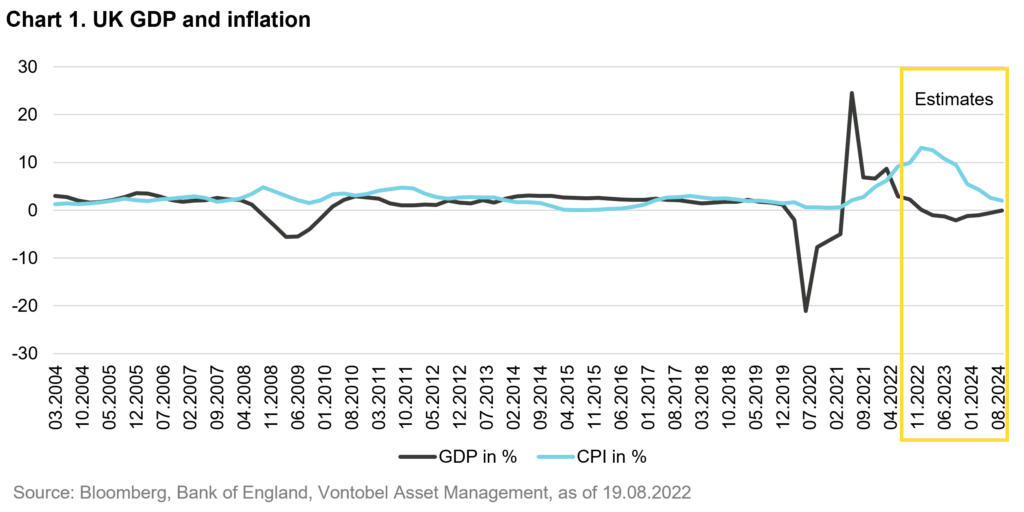

On a much more negative side, Bank of England economists “estimate that Ofgem (the UK energy market regulator) will raise its retail energy price cap by around 75% in October, … That would increase the typical household fuel bill from just under GBP 2,000 to around GBP 3,500, three times higher than a year earlier”. This will certainly cause a sharp drag on UK household real incomes and spending, as well as a GDP decline of nearly 1% in 4Q22 (see chart projections).

Because of “gasflation”, the BoE will have to raise its target rate by 50 basis points in September, November, and December. Ultimately, the rate will peak at around 4% (according to the implied overnight rate on BBG as of 19.08.2022), which might leapfrog the tightening path of the US Federal Reserve going forward.

At the same time, the current frontrunner to be the next UK Prime Minister, Liz Truss, is pledging fresh fiscal support if she takes office. This will increase borrowing needs further at a time when the BoE will start reversing its quantitative easing. Increasing short-term rates and more upcoming supply at the long-end will hamper capex while the cost-of-living crisis will dent consumption. Paired with double-digit inflation, this sets the stage for textbook stagflation in the UK for months to come.

Unease is stronger than expected in China – and consumption too low

The Chinese economic data for July came as a negative surprise, raising further doubts about the scale of the country’s growth rebound. Bank loans and total financing came in almost 50% below expectations in value terms, industrial production rose “only” 3.8% (year-on-year, compared with 4.5% expected) and, above all, retail sales rose by 2.7% instead of the 4.9% expected. The plunge in house sales is less surprising. Some weeks ago, the Politburo dropped its 5.5% growth target for 2022.

In reaction, the Chinese central bank (PBoC) has lowered two of its key rates (one-year lending facility and seven-day reverse repo) by 10 bps each. The authorities are still supporting the economy, but in small steps. Their focus is on long-term objectives. In the real estate sector, for example, in addition to reducing certain excesses, it is a question of adjusting the weight of the sector – still around 25% of GDP, including all ancillary activities – in regard to demographics and other sectoral priorities. At the same time, the authorities want to avoid a deflagration of the sector in the short term and have announced various initiatives to guarantee loans from some (but not all) real estate developers. Again, bond picking will matter here. In the end, the Chinese currency will have depreciated by nearly 2% since August 10.

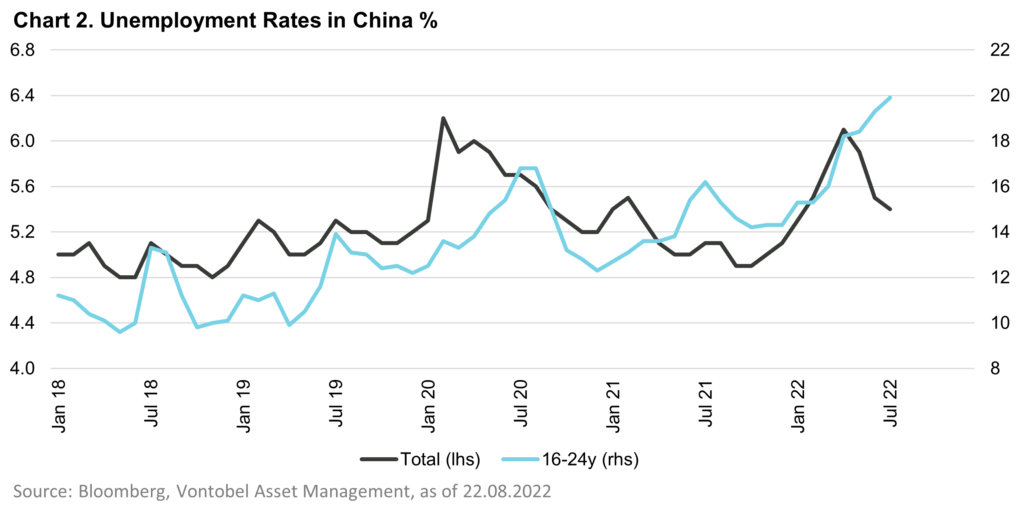

More concerning is that the various measures to rebalance the economy, including the sanctions against big tech companies, which have caused youth unemployment to soar to unknown levels ¬– nearly 20%. In this context, it is not surprising that households prefer saving to consumption.

European high-yield spreads: already bleak, but is it bleak enough?

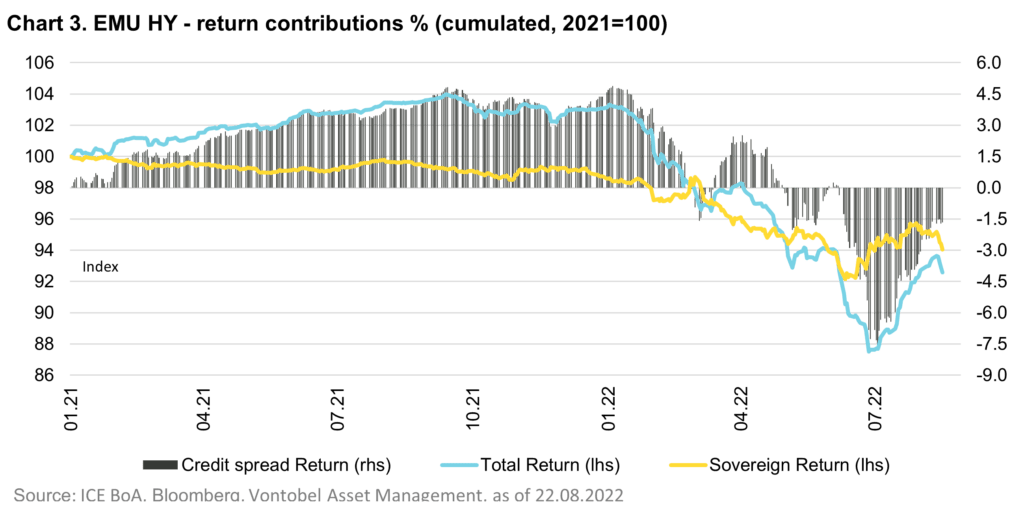

The credit universe suffered a slight correction last week – a little over 1% in European HY for example (blue line above), and 1.4% for the same segment in the US. This negative performance has been due to the sovereign yield component (pink line) rather than the credit risk (yellow bars).

The difference with the US is particularly noticeable since the beginning of the year, with respective performances of -10.1% and -7.8% (ICE-BoA indices). The difference is explained by the higher credit risk deterioration in Europe, which echoes the recession scenario considered as almost certain for Europe. Indeed, the credit component shows a loss of 6% since the beginning of the year (against -3.3% in the US).

The current European spreads, both HY and IG, implicitly reflect default rates at their highest level in five years. No one can rule out the worst-case scenario. Hence our preference for European low IG and our retreat from US HY, the most “optimistic” segment of all. If demand starts to contract globally, the latter may be the most exposed.