2022 reminded investors of a few home truths. Here are some key lessons we took away from a turbulent year.

Lesson 1: Inflation hurts all financial assets.

Portfolios that had apparently been diversified suddenly weren’t, while bonds proved to be anything but risk free.

After decades of lying dormant, inflation came back with a vengeance. And the world was reminded that it is bad for consumers, savers, the poor…and investors. Portfolios that had seemed to be sensibly diversified suddenly weren’t while supposedly “safe” sovereign debt wasn’t.

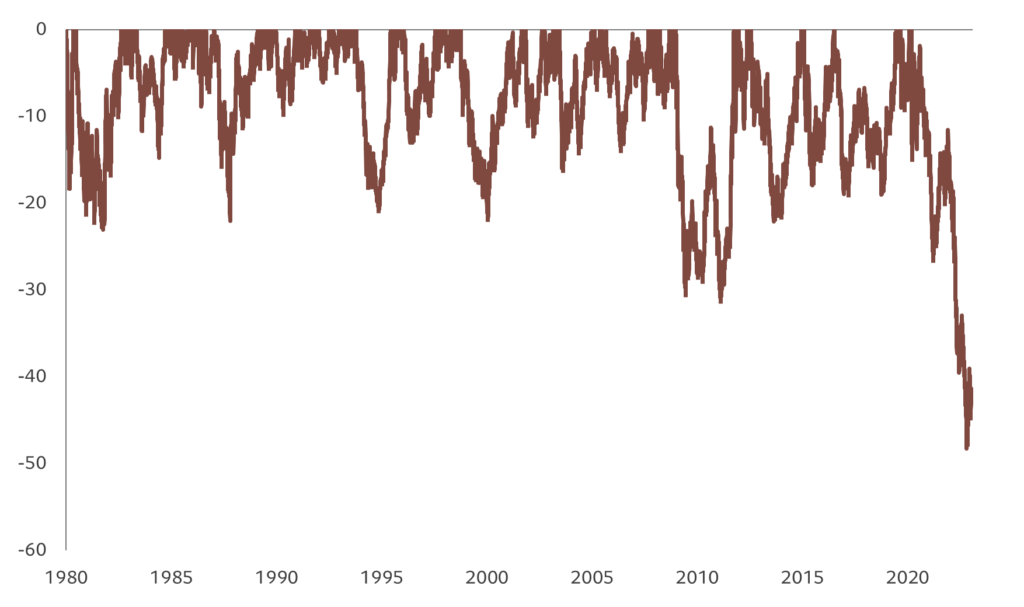

Figure 1 – Not so safe haven

US 30 year Treasury bond loss from all-time high, %

Source: Refinitiv, data covering period from 01.01.1980 to 09.01.2023.

Confronted with soaring inflation and a sharp tightening of monetary policy, both stock and fixed income markets sold off heavily. Correlations between equity and bond prices turned from very negative to record highs. Bonds fared as badly as equities normally do during an average recession – US 30 year Treasury bonds lost 44 per cent peak to trough while equivalent German bunds lost nearly 50 per cent, even more than they did during the high inflation era of the 1970s and 80s. That’s because yields were a paltry 2 per cent when the sell-off started now, compared with around 10 per cent in the early 1970s.

Cash proved to be the only true diversifier, though double digit inflation also guaranteed a loss of purchasing power for those holding it.

Only real assets managed to buck the trend and even then only for a time. Commodities ended 2022 up some 7 per cent on the year and US property gained 10 per cent. But those gains mask some violent price swings. Since June, commodity prices have collapsed 30 per cent while residential real estate is in a tailspin everywhere.

Lesson 2: Central banks are taking no risks in re-establishing their inflation-fighting credibility.

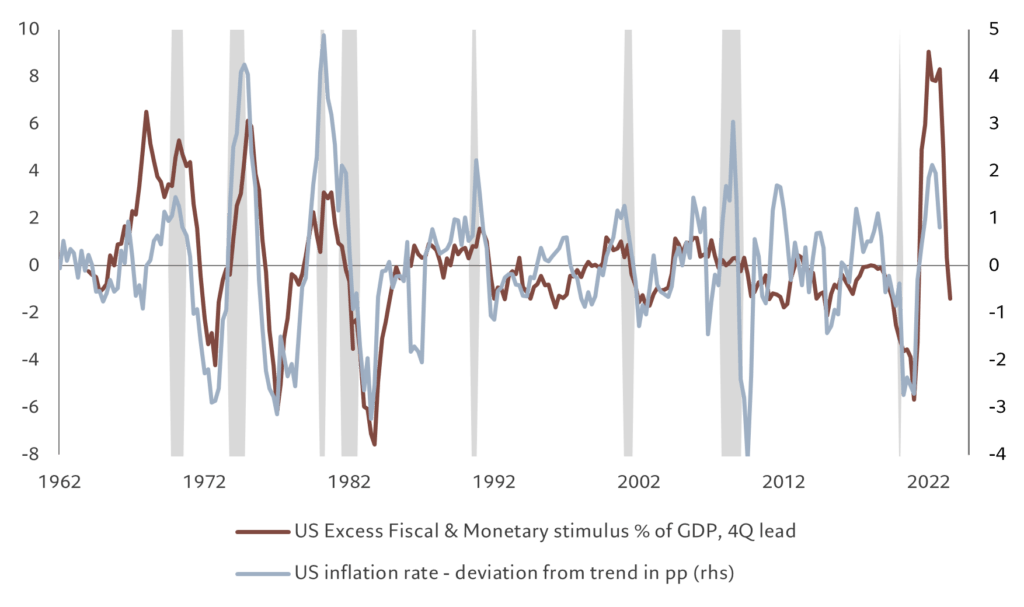

Despite central bankers’ firm assurances that inflation was a transitory phenomenon, it rose higher and lasted longer than anyone expected. The massive flows of fiscal and monetary stimulus in response to the pandemic were, in hindsight, clearly a policy blunder, similar to the mistakes that led to the Great Inflation of the 1970s. Policies intended to stabilise final demand instead triggered a massive demand overshoot at a time of significant capacity constraints. Inflation was an obvious and inevitable result – as orthodox economics predicted.

Persistent inflation, rising into double digits, threatened to de-anchor inflation expectations and to trigger a wage-price cycle. Central bankers realised their credibility was at stake.

Figure 2 – In excess

US excess monetary and fiscal stimulus (as % of GDP) and US consumer price inflation, year on year %, deviation from trend*

*Excess” fiscal stimulus is a measure of how much the government budget deficit exceeds the level consistent with the stage of the business cycle (i.e. the output gap – the difference between real GDP and real potential GDP); “excess” monetary stimulus is the deviation from trend of US M2 to potential nominal GDP; ** trend inflation rate is calculated using a H-P filter. Source: Revinitiv, Pictet Asset Management, data covering period from 01.01.1962 to 28.12.2022

A year ago, the market was pricing in only two rate hikes for 2022 in US and none in Europe. Fast-forward 12 months and the Fed has delivered 425 basis points of hikes, the ECB 250 bps. And they seem far from done. Monetary conditions have been tightened at the fastest pace since the 1980s, mortgage rates have surged and the risk of recession material. It’s been brutal. So far, central bankers are managing to convince the markets they’re taking inflation seriously. Economists expect US inflation to halve this year to some 4 per cent. More importantly, inflation expectations, as measured by the Fed’s favoured 5-year 5-year forward breakeven rate, have eased to 2.1 per cent from 2.3 per cent. But any sort of lapse, where inflation starts to rise again because of a premature easing, would be seriously damaging to their credibility. This, in turn, raises the risk that central banks will go too far with tightening and drag their economies into recession – which would cause a different sort of damage to their credibility.

Meanwhile, policy mistakes aren’t limited to central bankers. The UK government’s surprise September announcement of a GBP45 billion unfunded tax cut plan – one of the largest in history – triggered market panic and an epic crash of UK government bonds. The 30-year gilt dropped an unprecedented 8 per cent in one day. The Bank of England was forced into an emergency intervention to bail out the UK pension system, the government resigned and the incoming administration took note by replacing munificence with austerity. Which reminded central bankers that bond vigilantes are as powerful as ever.

Lesson 3: Economies adapt surprisingly well.

They adjusted to the effects of the Ukraine war faster than people expected, while Covid seems to be having smaller long-term effects than feared.

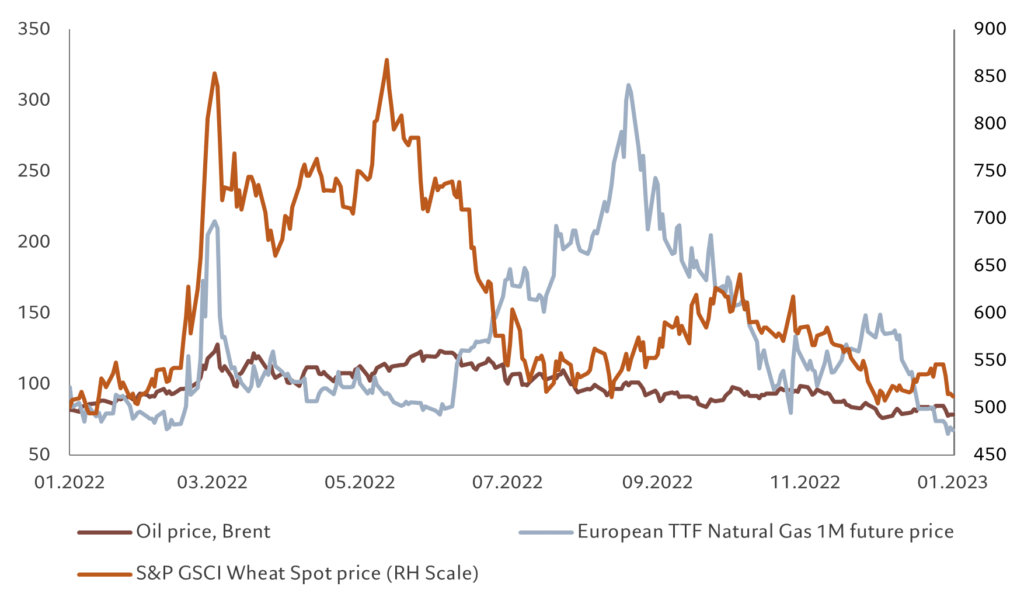

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February has been a generation-defining geopolitical shock. Markets and especially commodity markets reacted with panic and disbelief. But less than a year on, oil prices, European natural gas and wheat prices – commodities most directly impacted by the war – are all back to pre-war levels. And even though the situation on the ground hasn’t improved and escalation remains a real risk, investors’ attention has shifted elsewhere.

Economies, not least those in Europe, have shown a remarkable ability to cope with the shock. Demand for expensive fossil fuels dropped without undermining output – though a mild winter so far has helped. For instance, German industrial production and real GDP both managed to rise marginally over the year even as the country’s gas imports dropped 30 per cent.

Figure 3 – What went up also came down

Oil, natural gas and wheat prices, USD

Refinitiv, Pictet Asset Management. Data covering period from 06.01.2022 to 06.01.2023.

There’s a similar story for the Covid pandemic, which is likely to have smaller long-term effects than seemed certain in the depths of lockdown. The expected surge in automation, digitalisation, the acceleration towards green transition and never-ending policy stimulus have proved to be somewhat wide of the mark. The online share of total retail sales, for instance, is back at its pre-Covid trend.

One obvious legacy of Covid-19 seems to have been a shift in the relative power of labour versus capital as the workforce has shrunk while firms re-shored their production. There’s also been a re-rating in the value of living space, as working from home and hybrid working models have become the new normal.

Lesson 4: Where you are affects how asset markets look.

Regional effects are strong and currencies matter.

The year reminded investors that where they call home matters for their investment portfolios. For instance, UK and Japanese investors saw limited portfolio losses thanks to the significant outperformance of their local equity markets. At the same time, the depreciation of sterling and yen inflated the value of UK and Japan-based investors’ foreign holdings. Meanwhile, in Europe, contrary to the US and China, equities have significantly outperformed government bonds.

Lesson 5: China stands apart

Chinese assets need to be considered separately from emerging markets and developed markets alike.

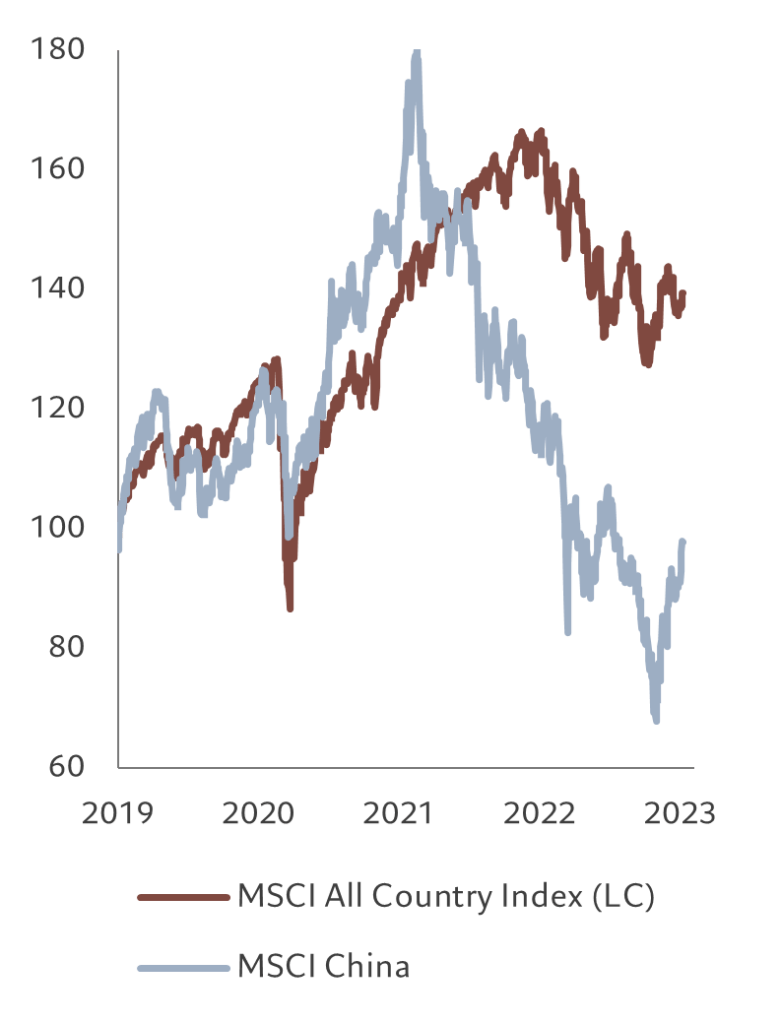

Chinese equities were hit by a triple whammy since they peaked in 2021. The government launched regulatory overkill on businesses, rigid zero Covid policy crushed demand, and the housing sector crashed. As a result, China’s economic growth flagged and the country even saw deflation at a time when the rest of the world was struggling against rising prices.

Source: Refinitiv, MSCI, Pictet Asset Management, data covering period from 01.01.2019 to 09.01.2023.

Then there was the flight of foreign investors. Clearly, given China’s growing weight and importance in global markets and its frequently divergent macroeconomic policies, the country’s stocks and bonds are both too big to ignore but also carry unique risks.

But Chinese exceptionalism doesn’t make the country un-investable. The Peoples Bank of China is now cutting rates. Beijing has taken steps to stabilise the housing sector with a combination of subsidies, cheap financing and lighter regulation. President Xi has de-facto made a U-turn on zero Covid by opening the country’s borders and scrapping mass testing and quarantine rules. Investors are taking notes – China’s equities are surging. Valuations are back in neutral territory, with its stocks trading at a 30 per cent discount to global equities – the discount was less than 10 per cent in early 2021. But to sustain these gains, Chinese corporations need to deliver on profit growth – which we expect to happen in 2023.

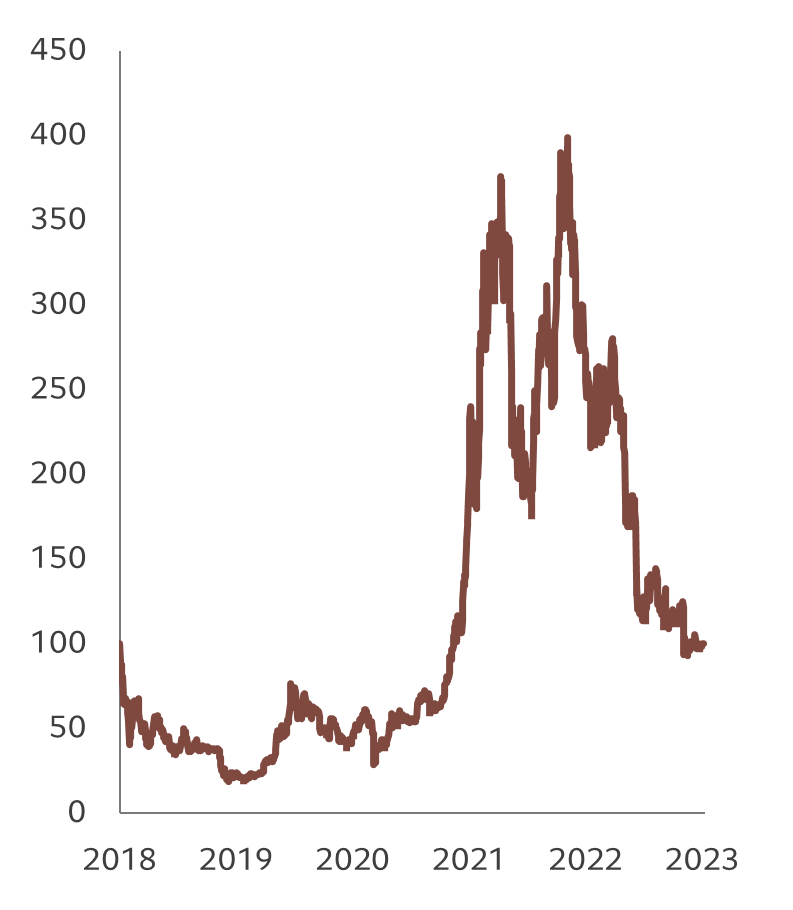

Lesson 6: Every bear market exposes new ways of losing money.

As Warren Buffett noted, it’s only when the tide goes out that you discover who’s been swimming naked. Now, as the flood of liquidity that was pumped into markets by central banks worldwide over the past decade starts to drain away, investors are starting to discover the difference between quality assets and specious ones. In some cases, these assets have been legitimate but priced at extreme valuations supported by little more than cheap money – particularly among some tech stocks. In others, it’s hard to identify the underlying value, such as Bitcoin, which soared 10-fold during the pandemic, only to collapse later; or Non-Fungible Tokens, which seemed to be fuelled by fumes. And finally, there are the outright frauds, many of which are now being uncovered in the world of cryptocurrencies. All of these are being exposed as liquidity evaporates – the discipline of monetary tightening can be brutal.

Source: Refinitiv, Pictet Asset Management, data covering period from 05.01.2018 to 09.01.2023.