Corporate Japan’s governance overhaul is about to enter a new phase, boosting the long-term appeal of Japanese stocks.

Some 18 months after Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida pledged to deliver a “new form of capitalism”, the contours of his revitalisation programme are finally becoming clear.

His flagship initiative, aimed at boosting economic growth and addressing social challenges, appears to be based on a simple strategy: persuading Japanese citizens to buy domestic stocks.

Kishida is urging the country’s traditionally risk-averse, cash-rich investors to manage and invest their assets proactively.

His administration is introducing a new tax exemption scheme for investment that, combined with other private-sector measures, is designed to accelerate a switch from savings to investment, enhance the long-term value of Japan Inc, and redistribute wealth.

“The Japanese are increasingly taking action to safeguard their financial future, which could prove transformative for Japanese stocks: domestic savers have some JPY2,000 trillion (USD15 trillion) in their coffers. “

These incentives have struck a chord with Japanese citizens. The return of inflation, which is running at a 41-year high, and mounting concerns over the cost of retirement have prompted a growing portion of Japan’s population to take action to safeguard their financial future.

Should this gather momentum, it could prove transformative for Japanese stocks: domestic savers have some JPY2,000 trillion (USD15 trillion) in their coffers.

But, just as importantly, such efforts could also boost Japan’s appeal among foreign equity investors, turning previously conservatively-managed businesses into the dynamic, lean, shareholder-friendly companies that are investment staples for global portfolios worldwide.

New NISA

Japanese retail investors have traditionally placed nearly half of their wealth in cash and bank deposits.

Only 15 per cent of their assets are held in stocks and investment trust funds, compared with around 30 per cent in the US and Europe.1

After many failed attempts by previous administrations, Kishida is working to unlock this huge cash pile.

In order to lift the share of equities, he is overhauling the tax-exemption scheme for investment, also known as the Nippon Individual Savings Account, or NISA.

Originally introduced in 2014 and modelled on the UK’s Individual Savings Account (ISA), NISA gives investors an exemption of the 20 per cent tax normally levied on capital gains and dividends for annual investments of JPY1.2 million a year and up to five years.

From January 2024, the tax-free annual investment limit will effectively double and, more crucially, become permanent.

For the first time, investors can sell an investment but retain their tax shelter, removing a major disincentive of the old structure.

Domestic investors have the potential to become a significant new source of demand for the country’s equity market, which is the second biggest in the world. Japanese investors have in recent years sought higher returns abroad, but the allure of foreign assets is fading.

One of the risks that always concerns the Japanese investor — whether institutional or retail — is currency volatility.

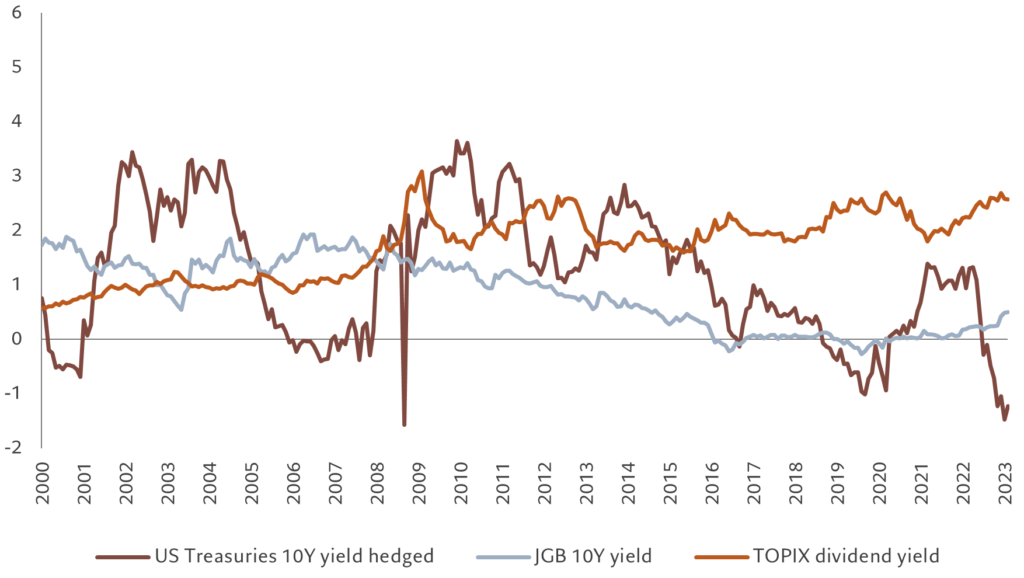

Typically, Japanese investors have been happy to take higher foreign yields but have always hedged away the currency risk. However, now the cost of hedging has shot up to a level which outweighs the positive yield differential.

The three-month hedging cost from the dollar to the yen, for example, stands at 5.2 per cent, compared with the yield differential of 3.4 per cent between 10-year US Treasuries and 10 year Japanese Government Bonds. This means the 3.5 per cent on US Treasuries becomes a negative 1.8 per cent after hedging, comparing unfavourably to Japanese stocks which offer a 2.6 per cent dividend yield.2

Fading appeal

Overseas assets are not longer appealing after FX hedge cost

Stakeholder to shareholder focus

If Japan is to become a nation of shareholders, this also augurs well for foreign investors. Not least because the emergence of a large domestic shareholder base should accelerate efforts to raise Japanese corporate governance standards.

Traditionally, Japanese companies have had to cater to the needs of a very broad group of stakeholders, including employees, customers and business groups.

The lack of focus has led to an inefficient use of capital. It is not for nothing that half of the companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange have persistently commanded a price-to-book ratio of below 1 and return on equity below 8 per cent. This compares poorly against a return on equity of 19.4 per cent for the S&P 500 — albeit at a price-to-book ratio of 3.9.

But the expectation now is that Kishida’s renewed drive to establish a culture of share ownership across Japan will add greater momentum to the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s own efforts to improve corporate governance and shareholder returns.

Frustrated that these flagship companies “have no concerns about violating the continued listing criteria to make efforts to enhance medium- to long-term corporate value”, the TSE has demanded that repeat offenders disclose management policies and plans to improve their capital efficiency of their balance sheet and their profitability or face delisting.

With Kishida’s reforms, the aspiration to improve governance and shareholder returns among listed companies in Japan is burning more strongly than ever.

That should in and of itself be a reason for international investors to consider rebuilding their exposure to Japanese stocks.

Yet the fundamental case for doing so is also compelling.

By our calculations, the country’s economy is expected to register the fastest rate of growth in the developed world this year of 1.5 per cent, fuelled by a rise in investment and spending by cash-rich companies and households.3

Looking further ahead, we expect Japanese equities to deliver an annual return of over 10 per cent in the next five years, outperforming US equities and almost matching returns from emerging equities in dollar terms yet with far lower volatility. The returns could be even higher if reforms have their desired effect.

This means Japanese equity should be a more prominent feature of international portfolios.

Overseas investors have in aggregate underweighted Japan for much of the past two decades. Currently, foreign equity portfolios’ allocation to Japan is at its lowest level since 2012.

Yet as corporate Japan’s priorities change, and domestic investors are starting to favour their own market again, the incentives to lift those allocations are building.

Japan’s stocks should be a bigger component of every investor’s portfolio.

[2] See Secular Outlook

[3] Bloomberg as of 24.03.2023