As a whole, major emerging markets (EMs) have become more resilient since the crises of the 1980s and 1990s.

Since the passing of COVID-19, headlines have not made for pleasant reading for investors. Rate hikes, invasions and banking stress have all made market participants sweat. Recession risk has replaced viral risk as the dominant market narrative.

Bad news has certainly impacted returns from EMs. Investors have borne considerable pain following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with Russian bonds effectively in default with zero recovery rate. The example of Russian sanctions, which barred payment on dollar-denominated debt, must also be playing on the minds of holders of debt among non-US allies.

However, the more traditional form of EM crisis, via external vulnerabilities, has been largely absent. Barring Turkey, most EMs have been well insulated from the global turbulence. Are we waiting for the other shoe to drop here too? We can answer this question by looking at our own country risk model, coupled with lists of crises across countries compiled by the IMF.

EM risks: a work in progress

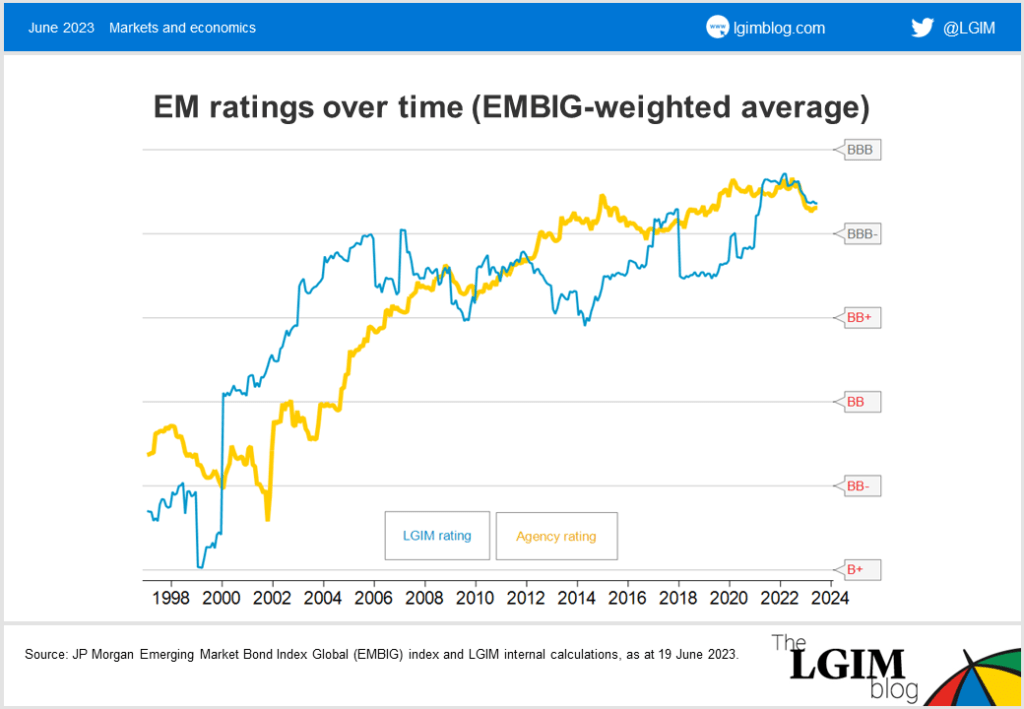

Though the broad EM universe is large and varied, we focus on the predominant markets[1]. Reviewing risk ratings, we see an ongoing improvement in the EM risk profile, reflected in both our country risk rating and agency ratings. Our index scores EMs against 44 indicators that predict financial crises. Each indicator has a threshold beyond which crises become more likely. EMs are rated based on how many thresholds they clear out of the 44.

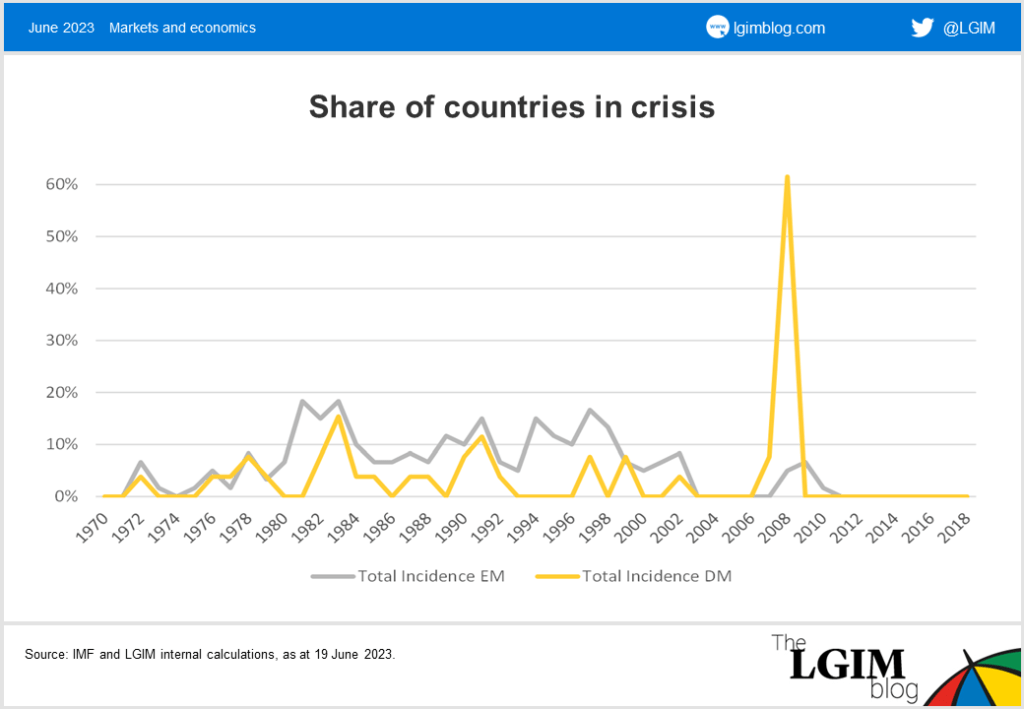

IMF data also show receding EM risks. By segmenting crises between EMs and developed markets (DMs) and examining crisis incidence across time, we can see that though EMs were more prone to crisis in the early 1980s and 1990s, the trend has been reversed since the mid-2000s, with banking crises in DMs becoming much more common.

Being smart and lucky

But if EMs are less risky than before, is this simply down to fortunate circumstances that will change in the coming years? We don’t think so.

To be sure, EMs have had their share of luck. The commodity boom of the 2000s insulated many from the external risks that had blighted EMs in the 1990s. The expansion of global trade was a collective effort largely outside of any one country’s control. But that’s not the full story.

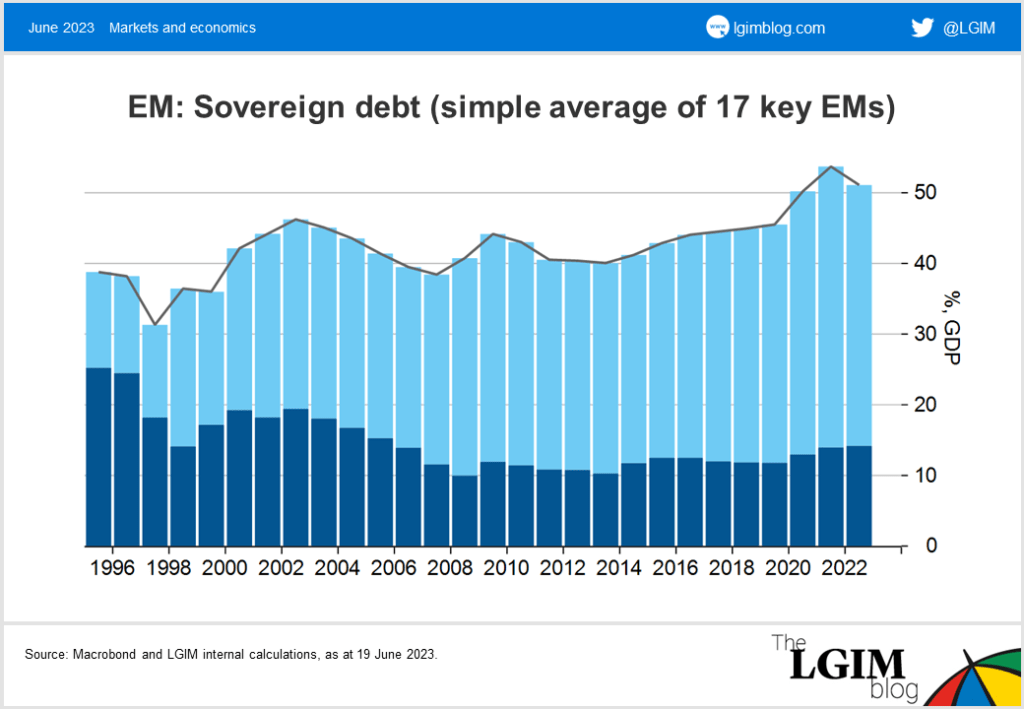

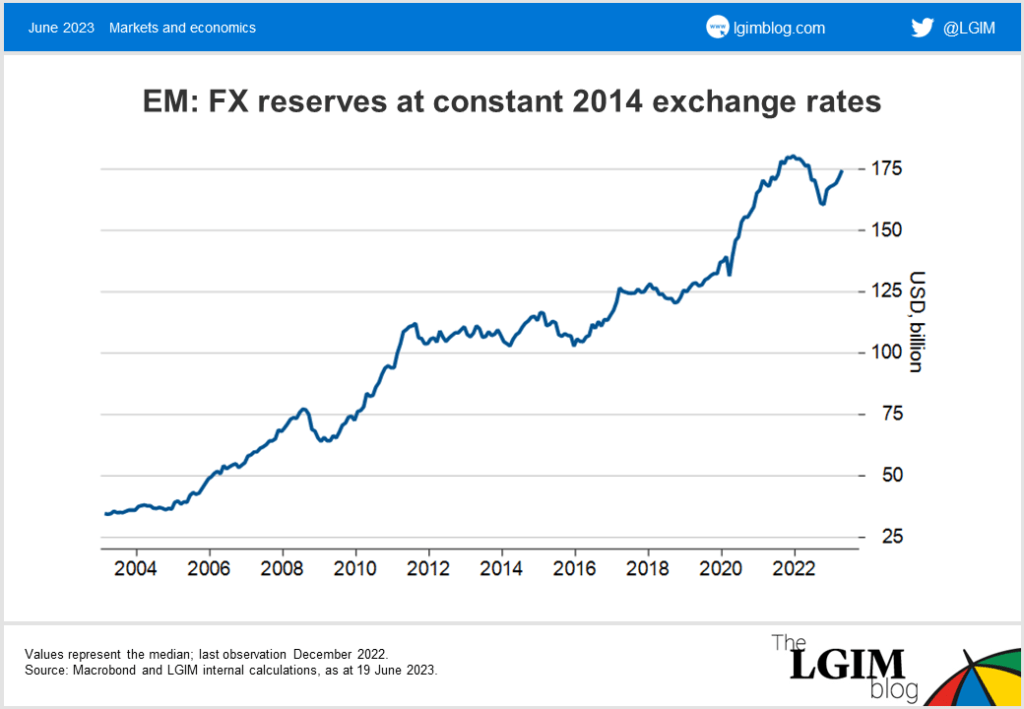

EM policymaking has also improved considerably. Dollar debt, a primary cause of previous EM crises, has fallen sharply as a share of GDP from the mid-1990s. Reserve volumes, essential for managing exchange rate risk and funding external imbalances, have also increased considerably.

Reaping rewards

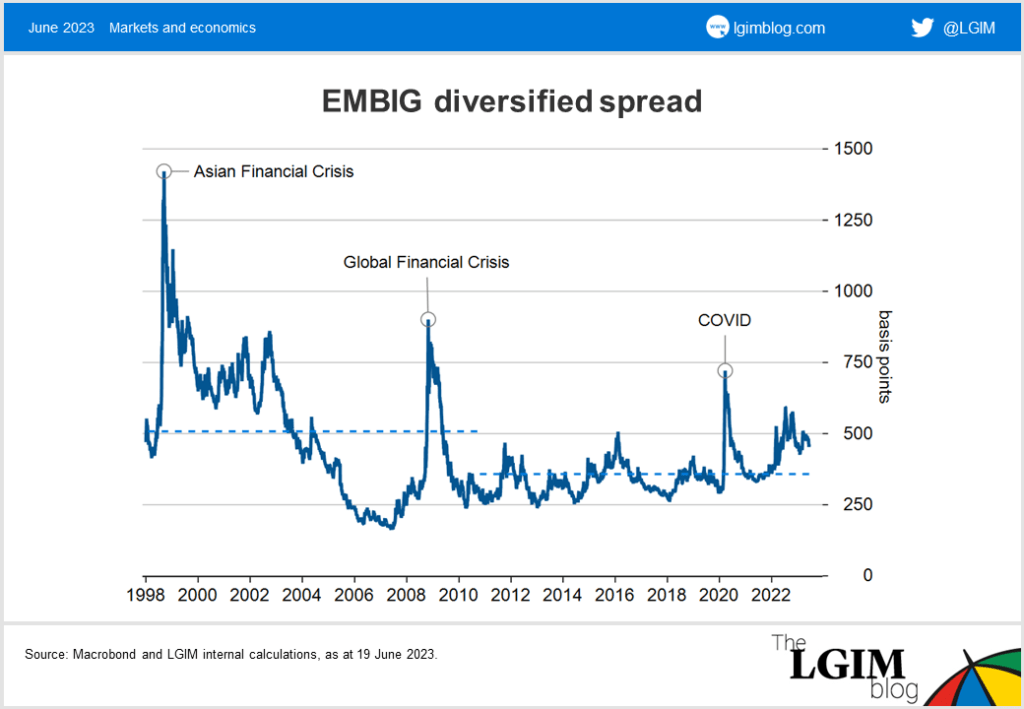

The benefits of de-risking have been apparent since the late 1990s. Since then, sell-offs in EM assets have become less violent over time, and JP Morgan’s Emerging Market Bond Index Global (EMBIG) spread remains relatively tight despite a strong dollar and tight US monetary policy.

We are strong believers in diversification, and we believe that EM assets in both equities and bonds can provide an important contribution to fully diversified multi-asset portfolios.

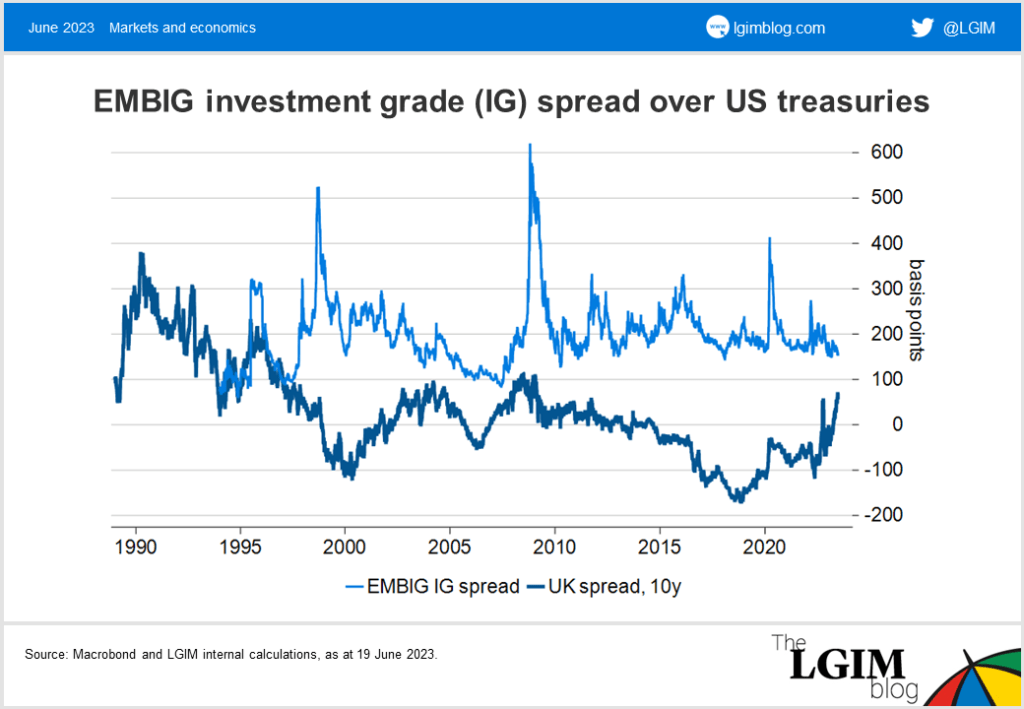

It is encouraging that the fundamentals of EM economies are improving and that could help to provide a counterweight to current risks in advanced economies. In recent periods of financial stress, such as the UK gilt crisis, sell-offs in the EMBIG have been more moderate than among DM markets.

Though the costs of past crises have been substantial, we believe that EMs are now enjoying the benefits of learning from their mistakes.

[1] Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czechia, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Poland, Philippines, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey