Investors have flocked to sovereign debt markets, attracted by high yields. But in appraising the riskiness of these bonds, they need to think about who else holds them.

As government debt loads swell to proportions not seen since the Second World War and inflation forces central banks to hike interest rates, investors are having to balance the attractions of some of the highest yields on sovereign debt in more than a decade against the risks of owning those bonds.

And one of the significant risks here is that some countries will face a strike by fixed income investors.

These so-called bond vigilantes have, in the past, forced governments into severe austerity measures by driving up the interest rates at which they were willing to hold freshly issued debt. And now that central banks are no longer able to buy government bonds as freely as they have been for more than a decade, non-state agents once again have the whip-hand in the sovereign debt market.

Weighing the risks

Which governments’ bonds are most at risk to investor flight is subject to complex factors. Investors need to consider, among other things, volume of debt outstanding, what the outlook for future deficits is, what economic growth is likely to be, what inflationary backdrop central banks face, where future investor demand is likely to come from, how soon existing debt matures and needs to be refinanced.

But one of the most important determinants is who holds the debt.

Such information is crucial because each group of bondholders – domestic central banks, domestic financial institutions, domestic retail investors and foreign investors – will treat the bonds differently, with foreigners much more likely to offload them when times get tough.

Domestic central banks are the most secure holders of their own country’s debt. For much of the past decade, central banks have absorbed significant amounts of sovereign debt onto their balance sheets. That was as part of quantitative easing programmes designed to stave off deflation and bring inflation to statutory target by reducing borrowing costs and stimulating domestic demand, particularly in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC) – 2 per cent in most cases.

Leading central banks’ balance sheets swelled to seven, eight or nine times their pre-GFC norms. But as long as inflation remained low, holding these assets wasn’t especially risky. Real interest rates were negative, and often nominal ones too. There was nothing to stop central bankers from taking a buy-and-hold approach to their bond portfolios; they would draw comfort from the fact that balance sheets would shrink as the bonds matured. They could absorb any market shocks by buying yet more bonds.

Central banks have fewer options now. If recession hits, they could feasibly stop selling the bonds they hold. But it’s unlikely they could begin buying them once more.

Domestic institutions such as banks and pension funds are also often buy-and-hold investors. They are often required to hold safe domestic assets – typically sovereign debt – as regulatory capital. Although here, sudden jumps in bond yields can threaten solvency crises, as occurred in the UK in September last year.

Less reliable are domestic retail investors. Although retail money tends to be sticky, retail investors will abandon an asset if they see running losses, though usually their flight will mark the asset’s capitulation.

Foreign institutional and retail investors are the most flighty. So the bigger proportion of the debt held by them the more sensitive the market is to the risk of sudden investor flight.

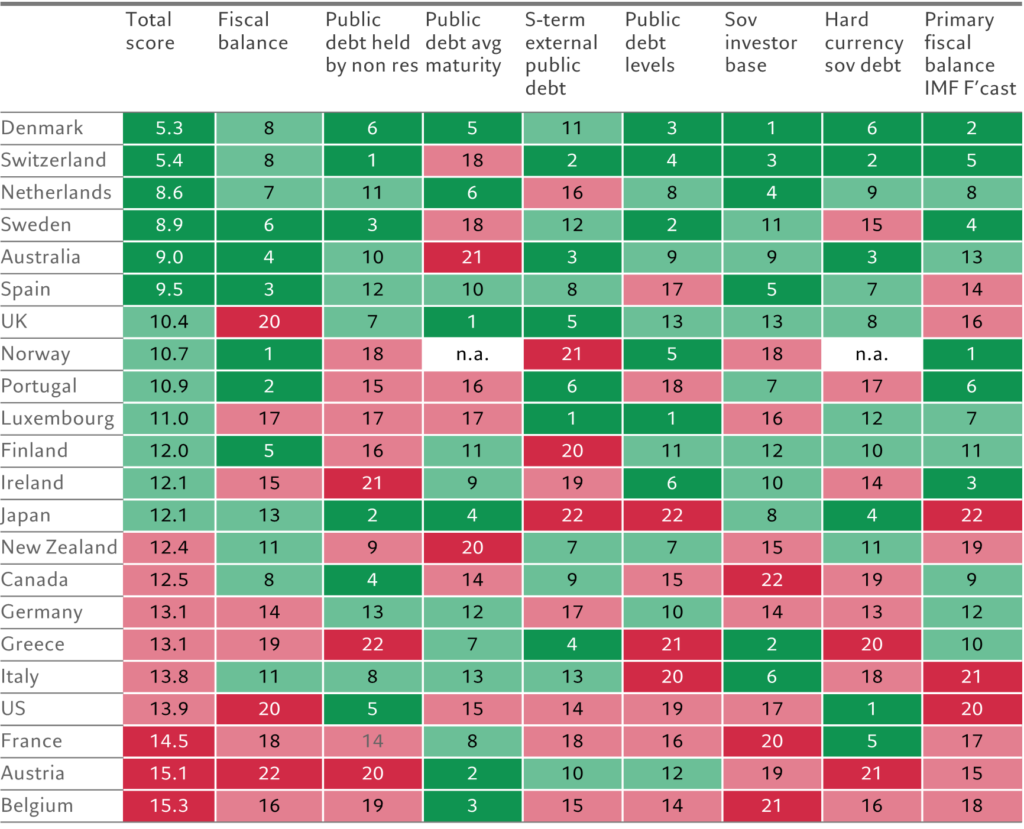

Figure 1 – Rating the risks

Sovereign risk score card, from lowest to highest

Follow the money

Our research shows that the riskiest bond markets are broadly the ones that rely on foreigners. How vulnerable a country’s sovereign bonds are to investor flight is a good proxy for the market’s overall riskiness for investors – as expressed in our sovereign risk model (see Fig. 1).

For instance, Denmark, Switzerland and the Netherlands are the top three ranking countries, ie those with the lowest fiscal vulnerability and are also least at risk of investor flight.

That makes sense. At the end of 2022, Danish financial institutions held the biggest percentage of domestic sovereign debt of any EU country.

On the other end of the scale, substantially bigger proportion of Canadian, Belgian and French public debt is held by foreigners. Factor in the fact that all three have debt loads in excess of 100 per cent of GDP and they all start to look vulnerable to capital flight.

“US, French, Austrian and Belgian bonds face the highest level of sovereign debt risk “

Of course, being vulnerable to investor flight is only part of the risk equation, if a rather relevant one. The other factors come to play too.

Combining them all leaves investors in US, French, Austrian and Belgian bonds facing the highest level of sovereign debt risk.

The US is in a unique position. Treasury bonds are held globally as a safe asset – investors tend to fly to US sovereign debt during times of crisis. But with such hefty foreign holdings of US debt, an overvalued dollar, high levels of domestic debt and big budget deficits could yet shake confidence in the market. The recent downgrade of US debt by Fitch ratings agency underscores the risks. Fitch cited “erosion of governance”, “expected fiscal deterioration” and “high and growing general government debt burden”.

Solvency concerns for developed country bonds seem far-fetched. After all, central banks have shown themselves to be ready and willing to buy domestic debt in times of market stress, while in most cases the issuance is in the domestic currency – though there are political ramifications in the euro zone. But as the UK showed in the autumn of 2022, market moves can be sudden and dramatic. And a high degree of foreign holding can make them extreme.