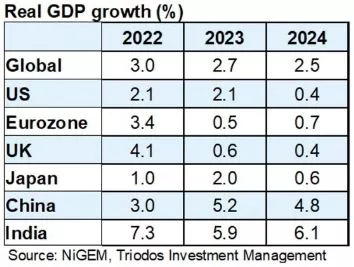

The major advanced economies are gradually slowing, but there is no broad consensus on the final destination. Quite some economists are convinced that this is a mere reversion to the pre-pandemic normal. We do not share that view, however, as we still expect a negative impact from the fierce monetary tightening further ahead, culminating in mild recessions in the US and the UK in 2024.

Risks have become more balanced, however, and recent data suggests the weakness might arrive later. For the remainder of the year, a continued gradual slowdown across advanced economies seems most likely. Combined with easing inflation and the end of the central bank rate hiking cycles, this should be beneficial for advanced economy risk assets.

The slowdown has only just set in

For almost the entire first half of the year, the global economy has performed better than expected. This certainly goes for the aggregate advanced economies, where economic growth in fact accelerated instead of slowing down. Clearly, the cumulative effects of the fierce monetary policy tightening by most major central banks were still not (completely) felt by consumers and businesses. Especially the US economy continued to defy expectations, with household consumption and business investment both recording healthy gains in the second quarter. The UK and the eurozone economies also left behind the period of (near) stagnation in the second quarter by growing modestly, although eurozone consumption remained weak. Japanese economic growth even accelerated sharply in the second quarter, as the weakened yen led to surging net exports.

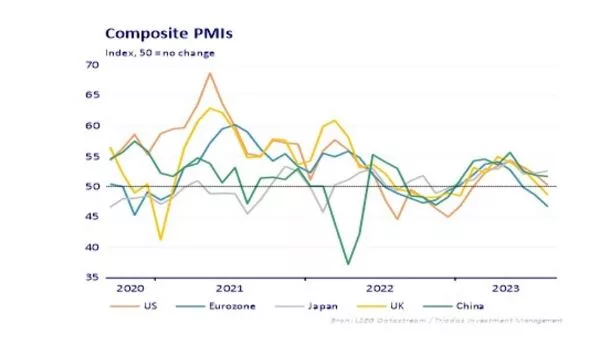

From June to August, however, global economic data started to come in slightly below consensus expectations for the first time in the year, because of unexpected weakness in the eurozone and China. Indeed, the closely followed surveys of supply chain managers (PMIs) suggest that eurozone and UK business activity is back in contractionary territory. China is experiencing a sharp slowdown, while US activity is approaching stagnation. Japan is the outlier, expanding solidly throughout the summer.

Mere normalisation, or towards contraction?

The main reason for the apparent recent slowdown across most major advanced economies seems to be the fading of one of the pockets of strength that has upheld growth so far this year: services spending. This could indicate that the COVID-related excess savings are starting to run out, especially in the US, where households have shown the most willingness to dip into these savings. It could also indicate that the burden of higher interest rates combined with still elevated inflation has spread from the consistently weak manufacturing sector to services consumption.

However, some caution in interpreting these survey signals is warranted. So far incoming hard data does not point to an imminent break in consumer spending, and even shows continued strong US spending. By some economists, this is interpreted as a sign that we are not at all late in the economic cycle, but merely in a normalisation process, moving back to the pre-pandemic situation. Granted, the tight labour markets should put a floor under near-term economic activity in all major advanced economies. But labour markets in advanced economies have started to cool gradually, with vacancies rates falling and the monthly number of jobs added to the economy declining.

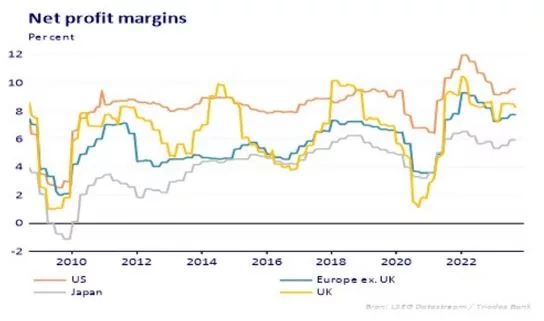

That said, ongoing robustness in corporate profitability make imminent lay-offs and significant cuts in capital expenditure unlikely. The most recent earnings reports for Q2 were again much better than consensus expectations, although admittedly the bar was set low. Net profit margins have also stopped falling for a few months now, stabilising at levels above the averages of the pre-pandemic decade.

The slowdown will gradually gather pace

Taken all together, the slowdown across advanced economies has not taken a flight yet. But slow-building tightening pressures do suggest increasing weakness further ahead. We therefore stick to our call for a mild US recession in the first half of 2024, although the chance that it will happen later in the year or not at all has increased. Eurozone growth will be sluggish going forward, but risks remain to be more to the downside, considering the latest data and the ongoing war in Ukraine. The UK is suffering from a wage-price spiral, likely forcing the Bank of England to hold on to its restrictive stance for longer than its advanced economy counterparts. This should result in a prolonged period of muted growth, including a recession later in 2024. The global slowdown will also slow Japanese activity growth, while Chinese activity will normalise with government and central bank support, which will be enough to prevent a global recession next year.

Continuing our slightly offensive allocation stance

Equities: staying overweight

Our call is based upon several developments: Firstly, Q2 corporate earnings were again (much) better than expected, and globally the upward revisions of forward-looking earnings per share estimates continue to outnumber the downward revisions. Secondly, we are approaching the end of the central bank rate hike cycle, with the Fed done and the ECB likely to pause after the summer. Thirdly, incoming global economic data keeps surprising to the upside, making near-term resilience likely. Fourth, investor sentiment is in neutral territory, meaning no contrarian signal from excessive optimism. And lastly, the banking turmoil in March has confirmed our belief that policymakers are determined to step in and ‘go big’ before any emerging financial stress escalates into an actual crisis.

Bonds: consequential underweight

For eurozone government bonds, the ECB’s financial stability considerations have always been the main reason for us to suspect that the sharp rise in yields since the beginning of 2022 was bound to be partly reversed in 2023. The ECB certainly wants to prevent any significant widening of spreads between Southern European countries and the German Bund. This was a reason for us to expect a lower terminal policy rate than markets were pricing in. Now that we have upped our policy rate forecast, and markets have started to price in a lower terminal rate, we are broadly in line with market pricing. Therefore, we are neutral duration. Nevertheless, the high interest rate environment could result in corporate financial difficulties further down the road, potentially triggering a rise in downgrades. We therefore continue to prefer high-quality names.