Inflation in China accelerated at its fastest pace in nearly three years in December, primarily driven by higher food prices. However, this upward move masks deeper deflationary pressures across the broader economy, especially in the industrial sector.

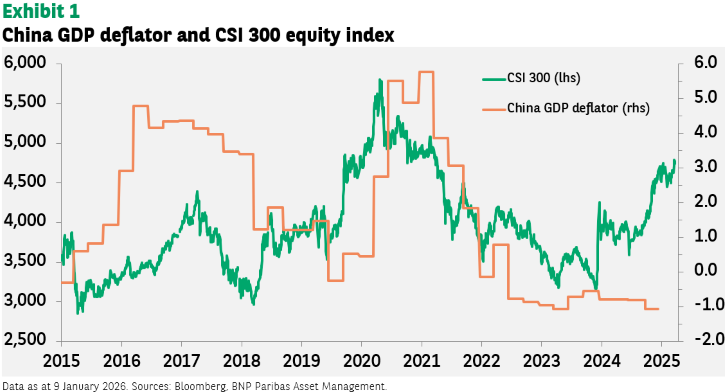

The country’s GDP deflator1 remains deep in negative territory, declining for the third consecutive year and marking the longest streak of economy-wide price declines since the late 1970s. For equity investors, the GDP deflator serves as a critical reality check on corporate performance, earnings growth potential, and overall market conditions.

Despite inflationary signs, China continues to grapple with deflationary forces. Plagued by a housing slump and sluggish consumer spending, the economy has struggled to overcome persistent deflation since the end of the pandemic. Overproduction in certain industries has resulted in an oversupply of goods, forcing companies to cut prices to stay afloat.

Equities diverge from broader macro trends

At the recent Central Economic Work Conference, top officials reaffirmed their commitment to the so-called anti-involution campaign, aimed at stamping out destructive price wars that have eroded profit margins across sectors such as electric vehicles and food delivery. However, progress has been limited as government concerns over potential job losses and slower economic growth have restrained aggressive policy actions.

Despite these macroeconomic headwinds, China’s equity markets achieved double-digit returns in 2025. This divergence from broader macroeconomic trends can be attributed to strong performance in sectors such as information technology, driven by breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI), biotechnology, and industries benefiting from anti-involution initiatives.

Additionally, improved liquidity has supported the re-rating of stocks as savings have flowed back into equities, with investors attracted by dividend yields that are more appealing relative to deposit rates. Meanwhile, fixed income returns have declined, market volatility has increased, and with the property market remaining weak, investors are seeking alternative investment avenues.

Going into 2026, weak private sector confidence, subdued consumer sentiment, and supply/demand imbalances are increasingly challenging factors for reflation, and ultimately for corporate earnings.

Reviving domestic demand is essential for sustained long-term growth, but redirecting the economy toward higher levels of consumption will take time. For now, policy remains focused on investment-led and trade-driven growth, emphasising the development of a modern industrial system and technological self-sufficiency. As such, investors should continue to focus on areas supported by this policy and technological innovation.

It’s all about AI infrastructure, for now

Global stock markets started on a positive note in 2026, continuing 2025’s upward trend, fuelled mainly by growing momentum in AI development. Market expectations suggest AI-related spending will surpass the 2025 levels as more companies adopt AI technologies. Some estimates project that hyperscalers, the large-scale cloud and data centre providers, will spend about $600bn in 2026, up from around $470bn in 2025.

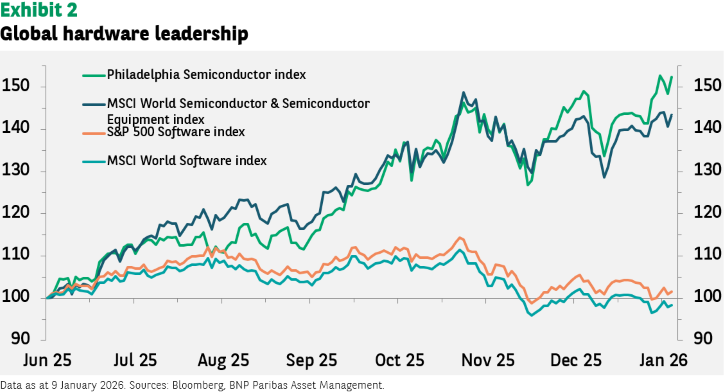

Notably, the recent rally has been driven less by companies developing core AI technologies themselves and more by ‘picks and shovels’ — the suppliers of the essential infrastructure and tools supporting AI growth. These include semiconductor manufacturers and hardware providers as well as providers of cloud computing platforms. All are expected to benefit from the increasing capital expenditure on AI development.

Investors currently focus on companies that supply the computational infrastructure needed to build AI ecosystems. Conversely, stocks in companies involved in AI software and ‘accelerators’ have seen more subdued re-ratings as their applications are still in early commercialisation stages and face greater uncertainty over growth.

The ongoing buildout of this complex infrastructure is likely to encounter bottlenecks including limitations in computing power capacity, the availability of datacentres, and the need for low-cost, reliable energy sources.

At this stage of development, computing power capacity is benefiting from a severe supply/demand imbalance, driving prices upward. For example, research provider TrendForce estimates that average dynamic random access memory prices rose by 50-55% in the fourth quarter of 2025, with orders for 2026 already exceeding available capacity. DRAM is a crucial component: it is the high-speed ‘working memory’ of a computer, providing rapid access to the data needed for active processing.

In addition, AI datacentres consume enormous amounts of power. New DRAM models that are being developed reduce energy consumption during data movement by 40-70%. That is vital for scaling AI ‘super-factories’ within existing power grids.

The hardware shortage is expected to continue until at least 2027, according to some estimates, as it takes two to three years to construct new computer manufacturing plants. This prolonged supply constraint is likely to benefit semiconductor companies more than others in the technology sector, not just in the US, but globally, and notably, in Asia where many of the supply chains reside.

[1] The GDP deflator measures the general level of price changes (inflation or deflation) for all domestically produced final goods and services in an economy. It is calculated by dividing nominal gross domestic product (at current prices) by real GDP (inflation-adjusted/constant prices) and multiplying by 100.