You step out onto a white sandy beach. You set up your towel and an umbrella and prepare to lay out and enjoy the day. Then, a plastic bottle washes up on the shore. And then another. Followed by yet another. Emblazoned on the side of one is the name of your favorite drink. The next one bears your shampoo label. And the last, your laundry detergent. This can’t be the kind of target marketing a brand manager had in mind.

As a consumer, you are upset and may now think twice about buying those products the next time you go to a store. You share your story with friends who also start noticing branded waste, which leads them to boycott products. Eventually, this change in consumer behavior eats into company sales.

As a citizen, you write a letter to your government representative. The government responds with new regulations, higher taxes and fines to persuade the brand owners to be good corporate citizens and clean up after their consumers.

A corporate sustainability mindset might have avoided this predicament altogether. It’s not just about good works but doing business right for the sake of long-term economic health. Investing to protect against future problems allows a company to grow the long tail of its business, where most value resides. Sustainability initiatives reinforce brand equity and broaden a company’s economic moat. Investors, companies, industries, and countries worldwide have embraced sustainability efforts at varying speeds and commitment levels.

In our view, businesses and investors are far better off if they anticipate and plan for the eventual expenditure today because, even before the spend is required, it will likely cause a dramatic shift in valuation. For some companies, that future is now.

Addressing sustainability: A boost to brand equity, competitiveness and cost of capital

Investors put capital into businesses for various reasons. Some only want the best returns possible, while others want investment dollars to improve the world. Sometimes these desires overlap, but often they don’t. The need for sustainable practices can be glaringly obvious from avoiding agricultural commodities where child labor has been employed, to beauty products that are tested on animals. Companies that are heavy users of water in areas where it is a scarce resource will clearly have to think about reclamation and reuse. But sustainability as a business or investing strategy is usually not so black or white. Consider solar panel manufacturers, which seemingly present a sustainable solution to producing zero carbon electricity. Trouble is, they often are not the most profitable businesses and some are now tainted by connections to forced labor, while analysis of their end-to-end lifecycle reveals issues related to mineral extraction prior to manufacture, plus open questions related to recyclability at end of life. Solutions to these and other sustainability issues will likely increase costs today, but ultimately should generate more loyal customers and higher profits, i.e. create a more sustainable underlying business.

The best corporate boards and management teams budget for sustainability efforts before a problem arises. It is no different from keeping up with maintenance on a factory or investing consistently in R&D and long-term brand-building. Some ignore the need, others so-call greenwash and only keep up appearances. Others investigate the potential damage and opportunity to their businesses and start to tackle a problem that could take a generation to solve. It’s left to investors to figure out the difference.

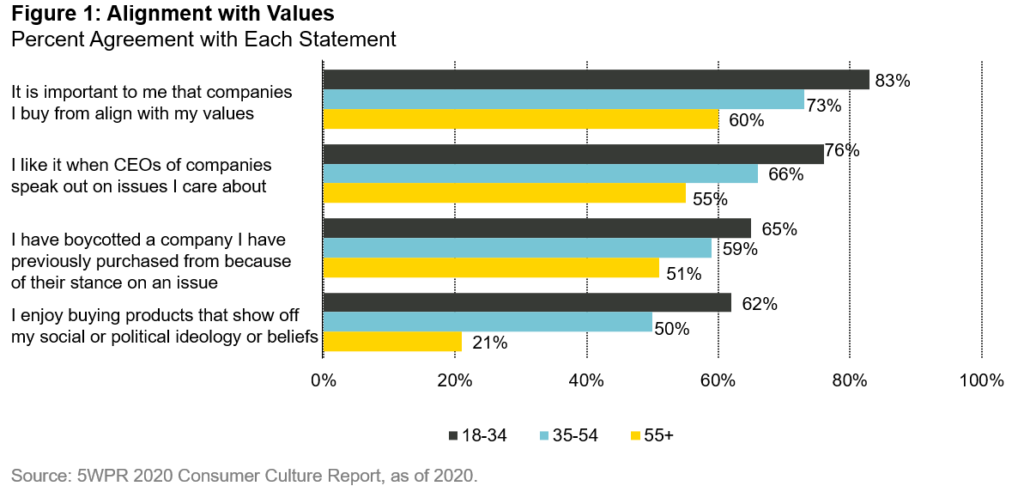

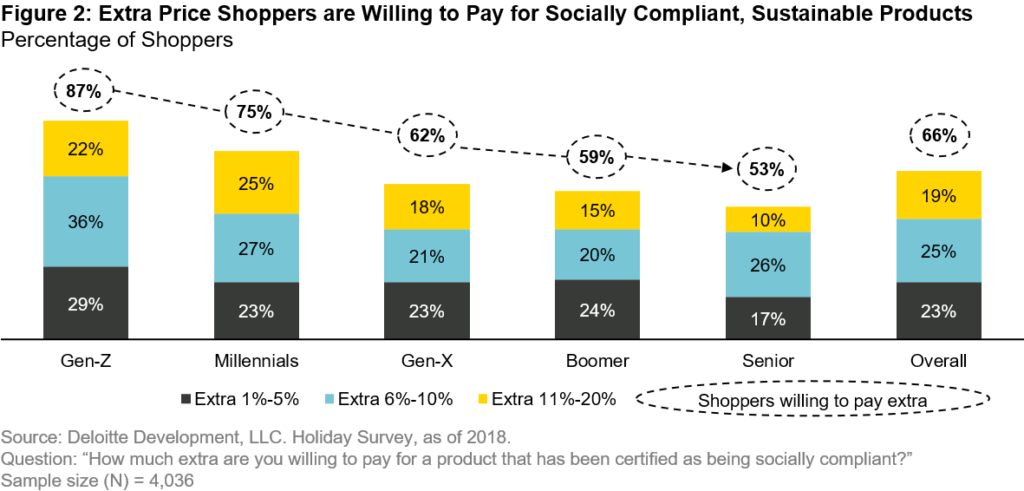

For their part, consumers are already differentiating. While estimates differ, the trend is clear – consumers care. Nestle estimates that 60% of purchasers today consider the sustainability of a brand at the point of sale, up from 50% only a year ago. These are not fringe consumers or exclusively Gen Z, but mainstream consumers across generations. These new consumer choices are not just about product or brand boycotts, they are an active decision to purchase a product that aligns with the consumers’ values (Figure 1). A Deloitte survey showed that 66% of consumers are willing to pay extra for a socially compliant sustainable product, with 19% willing to pay an extra 11-20% (Figure 2).

Environmental and social factors at the point of sale are not the only things that consumers care about. Price, taste, smell, efficacy, and packaging still come into play, too. But to be competitive, a product needs to offer much more today than it has in the past. Brands have historically had an emotional component, and companies controlled the messaging around the feelings that brands evoked through commercials and sponsorships. That emotional component is more ephemeral in an era where social media and other viral campaigns can wrest ownership of that messaging and turn a feel-good product into something toxic—or conversely boost sales when a brand is seen to represent doing the right thing.

Beyond a green premium on products, there are fundamental benefits from the transition to a more sustainable business model. Lower water and electricity usage, and less waste lead to lower operating costs. Once the capital investment on changing the business processes are spent, ongoing costs can be lowered, leading to a competitive advantage on the cost of production.

Employing sustainable practices also benefit business financing: green bonds and loans can be a competitive advantage as they lower the cost of capital. Both are used to support environmental projects and often come with tax incentives. Case in point: Anheuser-Busch Inbev (ABI) issued the largest ever ESG-related loan for over $10 billion earlier this year, with the costs linked to sustainability targets. On the opposite side of the spectrum, debt rating agencies downgraded ratings and lowered credit outlooks for oil companies as a direct result of climate risk and transformation costs—increasing the sector’s cost of capital. Moody’s recently downgraded ExxonMobil and stated, “volatility and uncertainty will rise over the medium to long term from growing efforts by many nations to mitigate the impacts of climate change through tax and regulatory policies that are intended to shift global demand towards other sources of energy or conservation.”

The cost of action

Quality management teams are proactively spending on a multitude of projects to manage these dynamic sustainability forces. They have plans to go carbon neutral at least at Scope1 1 and Scope 2. The most forward-thinking are already working on the much broader Scope 3 emissions. Others are moving to fair trade standards that can be audited by third-party organizations. Many are embarking on projects to improve packaging to use less plastic, or they are inventing new types of packaging to be more reusable, recyclable, or biodegradable, so that less waste will be dropped by the highway, float down a river and eventually end up on the white sandy beach where we started the discussion.

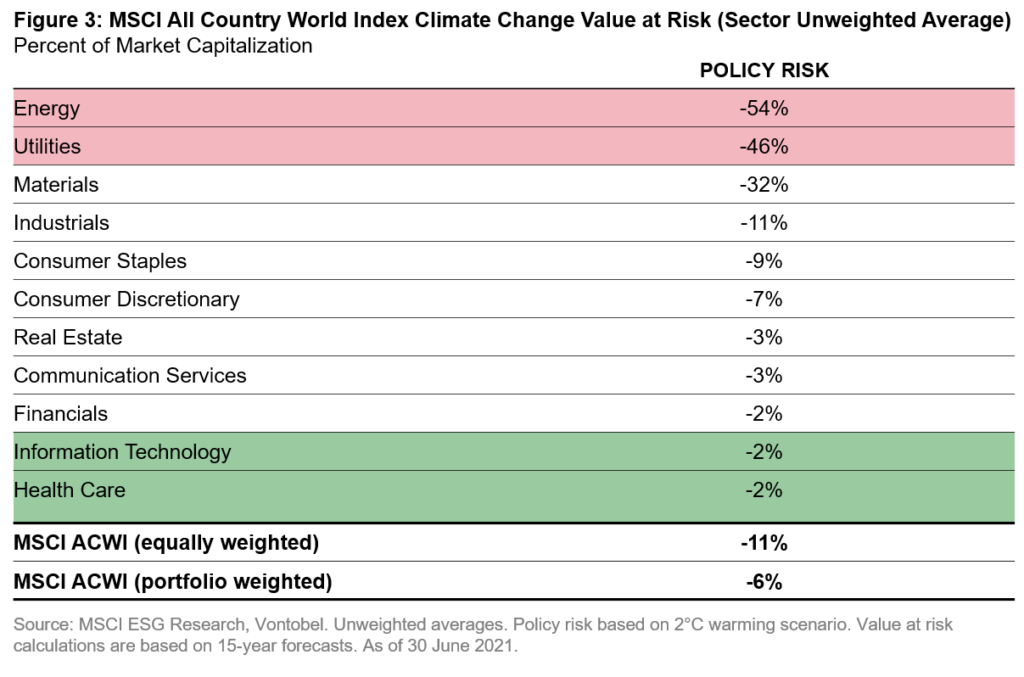

The price tag for sustainability by company varies widely – but it’s never cheap. Focusing on policy risk surrounding carbon emissions alone, MSCI estimates that to achieve the Paris Agreement targets, it will cost energy companies more than 50% of their market capitalization, on average, while those in the health care sector may only face costs of 2% (Figure 3). Analyst models and estimates don’t generally include these payments until the companies announce such spending or governments change regulations. To make it even more complicated, even within the same sector there can be major variations in necessary sustainability spending.

An investor needs to understand these differences across and within sectors to gauge the challenges ahead. For instance, within consumer goods, food manufacturers will have a tougher time than home and personal care companies reaching Scope 3 carbon targets. Both have packaging challenges, and even if a food company removes carbon from its manufacturing plants, it will increasingly be viewed as inadequate. Upstream suppliers to food producers may use carbon intensive fertilizers and depend on methane producing dairy cows. The overwhelming majority of greenhouse gas emissions lie in this expanded scope.

Most companies do not break out a specific cost of their sustainability projects. One exception is Nestle, which announced that it is spending $3.5 billion (USD) over the next five years on carbon initiatives, $1.6 billion on packaging, and $270 million on a packaging innovation venture fund. Combined, this outlay is roughly $1 billion a year. Stack that up against the size of Nestle, a $338 billion market cap company, and the expense is not all that great – it is less than 0.3% of the company’s value a year. But versus earnings, this investment toward greater sustainability is much more significant: up to 8% of the company’s profit. That money could be used for dividends, buybacks, reinvestment into organic growth, or acquisitions.

Is sustainability spending the type of investment that owners of the business should want? A cynic would say that 8% is too large a percentage of earnings to not allocate towards shareholders.

The cost of inaction

And what happens if companies opt to wait it out and avoid the upfront investment? At some point, more consumers are expected to move away from brands and companies that are not focusing on sustainability, and towards those brands that are. Furthermore, governments will demand that those companies purchase carbon credits or institute other initiatives. Fines could also be part of the equation. If a company is late to adapt, it will likely have to invest in sustainable practices anyway and, in the meanwhile, it will have lost brand equity and corporate goodwill. If a company does not lower the amount of carbon used in its supply chain today, it may be forced to make those same changes later and have to pay for carbon credits until it does.

Actually, any management team could continue to ignore sustainability mandates if they only have short-term investors. But both will be rolling the dice in favor of a major regulatory or social change not happening on their watch. But for longer-term investors, it’s our view that any valid company analysis today must include sustainability assessments, whether or not the current management team acknowledges the need. From a quality investing perspective, a planned expenditure is far superior to an unplanned one, and these days we expect management teams to outline their sustainability plans or explain why one doesn’t exist.

An (extreme) example of ignoring ESG risks is Vale, a massive state-controlled mining company based in Brazil, which violated E, S and G considerations, in a single catastrophic episode. In 2019, a Vale dam in Brumadinho, Brazil collapsed. Hundreds of people died, many of whom were employees, and almost 200 miles of river became polluted. Another Vale dam had collapsed only four years before and while the company had the opportunity to learn from the issue and make changes, it did not. After the second collapse, the company agreed to pay $7 billion in compensation and remediation costs. It also announced that it would decommission similar dams. A management team with a long-term mindset would have recognized the risk and spent the money ahead of a human and ecological disaster. Instead, it focused on the short-term math that may have indicated that it is more profitable to let tanks of noxious mud accumulate unsafely. The upshot? Former CEO Fabio Schvartsman, along with 15 other executives, was charged with homicide and environmental crimes. Vale’s stock declined over 20% in the two weeks after the collapse2.

More typically, a lack of ESG investment degrades brand equity slowly, over time. A company may lose customers to more sustainable brands for years before some management teams react. For others, the destruction to equity can come all at once – a dam collapse in Vale’s case, or an explosion deep offshore for BP. In 2010, as another poignant example, the Deepwater Horizon drill rig infamously killed eleven workers, hurt other employees, and destroyed the rig. It also caused one of the largest oil spills in history. The estimated overall costs were more than $65 billion, versus a budgeted drilling cost of $96 million. BP was subsequently barred from new contracts with the US government for several years.

Besides the fines, did this lack of urgency cause other destruction of monetary value for shareholders? While it is hard to quantify, we would assume this is the case. When a future mine or oil field is up for bid – would you want to be the politician who assigns it to a company with a clean history or one with a history of accidents? Would you want to work at a company that risked the lives of employees?

After the BP disaster, the US government set up the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling to investigate the causes of the failure and give guidance for future changes. While specific to the oil industry, and perhaps ironic to look here for guidance on sustainability, the foreword of the recommendations report3 includes a useful framework to think about these issues for all types of companies:

We recognize that the improvements we advocate all come with costs and all will take time to implement. But inaction, as we are deeply aware, runs the risk of real costs, too: in more lost lives, in broad damage to the regional economy and its long-term viability, and in further tens of billions of dollars of avoidable clean-up costs. Indeed, if the clear challenges are not addressed and another disaster happens, the entire offshore energy enterprise is threatened—and with it, the nation’s economy and security. We suggest a better option: build from this tragedy in a way that makes the Gulf more resilient, the country’s energy supplies more secure, our workers safer, and our cherished natural resources better protected.

Investors, managers, and boards can learn from this tragedy: sustainable business practices have costs and take time. Inaction has unseen future costs, too, which are usually much greater than the cost of preventative action taken today.

How to know if a company is taking its sustainability responsibility seriously

Public market investors are at a disadvantage when it comes to knowing if a management team is serious about its responsibilities. Unlike Nestle, most companies do not break out the specific cost of transforming towards sustainability. Investors often must rely on company targets without associated cost estimates. The best of these include specific targets, such as a 20% reduction in water or carbon emissions in five years, with annual updates on progress. In our experience, European companies lead the way here.

ESG scoring systems can be helpful but are not enough. There are many ESG score providers, and new ones pop up frequently. Each one has a different vantage point and uses different inputs to reach different conclusions. Investors should use ESG scores like they use broker research – it is only one piece of the puzzle. Active managers who have long-term relationships with companies, have conversations with management and board members, and have a sense of whether the company is focused on the short or long term have an advantage in making this judgment. We believe engagement, along with independent voting, is the most important part of the ESG effort.

Employee targets is another area to examine. Incentives tied to specific long-term sustainability targets should lead to better results. And increasingly we see boards including sustainability targets in management incentive plans.

Company collaborations can also verify sustainability initiatives. Unilever, as an example, works with many NGOs, partners with innovative companies and is on the board of groups working on sustainability issues. Unilever works with Loop, which distributes mainstream branded goods like Dove and Hellmann’s in reusable containers. It is part of Pulpex, along with Diageo and others, working on pulp bottles to reduce the use of single-use plastic. Unilever has 26 brands that comply with PETA’s Global Beauty Without Bunnies Program, received an award from the Humane Society and is working with the US EPA on developing ways to test chemicals used in consumer products without animal tests. These sorts of activities give investors confidence that management is taking its ESG responsibilities seriously.

Conclusion

We believe investing for sustainability is key to protecting a business’s corporate image and enhancing brand strength and is therefore an important driver of maximizing shareholders’ long-term returns. Complying with ever-changing customer and government demands will not be cheap or easy. A delay will manifest as a hit to sales and the companies will have to pay anyway – but with higher costs and at an unplanned time. Acting today also has benefits as it engages customers and helps to retain and recruit new employees, and can lead to lower costs in the long run. Higher quality boards and executives are ahead of such issues, which strengthen relationships with all stakeholders. This isn’t just about what’s good for the planet – this is about good business.

To many, investing in sustainability is common sense. To some, it is more of a bureaucratic waste of time with onerous new regulations. We believe it is clear that ESG is an integral part of evaluating business quality because, simply put, sustainability has a material impact on long-term value.

For a different angle on the many facets of sustainability please see Vontobel Quality Growth’s blog, Turning Stones , where we regularly highlight sustainability issues that informed long-term investors and management teams should be considering. From CEO pay, to water use, to modern slavery – Turning Stones uncovers and examines aspects of modern-day investing you did not learn in business school.

References

1. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol sets the global standards to measure and manage greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and breaks them out into Scope 1, 2, and 3. Scope 1 includes GHG emitted directly by a company such as generators and company cars. Scope 2 are emissions from purchased electricity that power a company’s operations. Scope 3 are emissions that stem from a company’s value chain from its suppliers (dairy farming for a food company) through to the end use (charging a product), through to product disposal.

Disclosure

The discussion of any investments in this paper is for illustrative purposes only and there is no assurance that the adviser will make any investments with the same or similar characteristics as any investments presented. The investments identified and described do not represent all of the investments purchased or sold for client accounts. The representative investments discussed were selected based on topics related to our ESG research. The reader should not assume that an investment identified was or will be profitable. There is no assurance that any investments identified will remain in client accounts at the time you receive this document.

Certain information ©2021 MSCI ESG Research LLC. This report contains “Information” sourced from MSCI ESG Research LLC, or its affiliates or information providers (the “ESG Parties”). The Information may only be used for your internal use, may not be reproduced or redisseminated in any form and may not be used as a basis for or a component of any financial instruments or products or indices. Although they obtain information from sources they consider reliable, none of the ESG Parties warrants or guarantees the originality, accuracy and/or completeness, of any data herein and expressly disclaim all express or implied warranties, including those of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. None of the MSCI information is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such, nor should it be taken as an indication or guarantee of any future performance, analysis, forecast or prediction. None of the ESG Parties shall have any liability for any errors or omissions in connection with any data herein, or any liability for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential or any other damages (including lost profits) even if notified of the possibility of such damages. © 2021 Vontobel Asset Management, Inc. All Rights Reserved.