Unlisted businesses involved in synthetic biology, the electrification of transport and other early-stage tech offer the potential of huge growth and a glimpse of the future, as the Private Companies team’s Chris Evdaimon explains.

All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk. Past performance is not a guide to future returns. Some Baillie Gifford portfolios have a significant exposure to private companies. These assets may be more difficult to buy or sell, so changes in their prices may be greater.

Investing in private companies involves attempting to predict the future.

We learn about and analyse new technologies, products and business models, hypothesising how they will be put to use to shape Tomorrow’s World.

We are using our imagination to predict how these scientific and technological breakthroughs can become ubiquitous, and build great businesses in the process.

Lithium ion batteries, for example, were developed in the late 70s and early 80s and have by now transformed the entire consumer electronics industry, as well leading the electrification of transportation.

As Elon Musk has said, “the first step is to establish that something is possible, then probability will occur”.

We assess this probability, together with the ability of founders to execute, for the benefit of our clients and the world at large.

Problem Solving

This paper explores how some of our private companies holdings are building tomorrow’s world. But first let’s contemplate the problems they’re trying to solve.

They include some of the biggest issues facing humanity: climate change, income disparity, online addiction and nationalism.

We believe our industry’s defining role should be helping to address these challenges. If the companies we back succeed, returns should follow from their positive impacts.

Let’s consider them one-by-one.

Climate Change

Images from this summer of people drowning in New York and the middle of Germany, and of vast areas being on fire simultaneously on both sides of the equator, should still be fresh in our memories.

Companies, investors and regulators are all in a frenzy to quantify environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria, and apply them to organisations.

But, as others have said, without the E there’s no S or G to worry about.

We must decarbonise everything possible as quicky as possible: our energy sources, our means of transport, how we heat and cool properties, the production of food.

The potential solutions present investment opportunities. We are researching companies from across the world that address climate change in different ways. These include:

- the electrification of transport

- carbon capture

- energy solutions that augment use of renewables and modernise power grids

- regenerative agriculture for carbon sequestration

- reduction of food waste

- growing food in indoor vertical farms

- cultivating meat without raising and slaughtering animals

Agriculture uses half of the planet’s habitable land and 70 per cent of our freshwater, and it’s predicted we will have another 2 billion mouths to feed and hydrate by 2050.

Scarcity of water will become an issue. We may even need to extract it from the air in some places. Believe it or not, early-stage companies are developing solutions precisely to do that, powered by solar panels.

Income Disparity

The income of the US’s top 10 per cent of earners is more than nine times higher than the average of the remaining 90 per cent.

For years, many companies have built products and services that focused on more affluent consumers’ spending habits. Yet many people face different sets of daily challenges and have very different demands.

About 150 million Americans have no savings, living paycheck to paycheck. There are therefore investment opportunities in rapidly growing private companies focused on addressing the needs of these underserved segments of the population.

For instance in banking, we have invested in Chime. Unlike most of the incumbent lenders and other neo-banks, it genuinely takes care of the underbanked – citizens who might have a savings account but are still denied access to many of the associated services that others take for granted. Chime offers a zero-fee bank account that advances wage payments by two days.

We also have a stake in Faire. It helps neighbourhood entrepreneurs make a living running physical retail stores, offering an alternative to the Amazon-dominated world of ecommerce. To do this, it provides the kind of inventory and logistics solutions that would normally only be available to large retail chains and big ecommerce stores.

In the same vein, our antiquated education system is not in synch with the jobs market of the near future. The Chinese government, valuing social stability above all else, acted to strictly regulate the leading domestic education companies earlier this year. It shocked the investment world and wiped billions of dollars off the firms’ value. But the government’s goal is to address the diverging gap in opportunities between China’s ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’.

In North America, among other potential corrective measures, we need vocational training to steer some youngsters towards tomorrow’s well-paid blue-collar jobs.

WorkRise is an example of a company engaged in this and is part of our portfolio.

It is training, certifying and placing workers in the energy industry, as well as easing transitions from oil and gas jobs to those involving renewables.

Online Addiction

The increased use of time to go online, and the way we consume internet-published content, is complex to address and difficult to reverse.

The average global time spent daily on social media is two hours twenty four minutes. For 16 to 24-year-olds it’s even longer.

Facebook alone accounts for 58 minutes of its daily active users’ time. For TikTok, the figure is a staggering 90 minutes.

When you add streamed content consumption and gameplay time, both of which exploded during Covid, you get to six to seven hours per day online. And the figure is rising.

There is a war going on for users’ time and attention, and it’s driving customer acquisition costs through the roof.

China’s state media has labelled this behaviour as ‘spiritual opium’, and you can’t help but notice the historical reference. For those of you who may have missed it, the Chinese government recently restricted online gaming for under-18s to just three hours per week.

We need to ask ourselves: are we truly happier with our online habits? With 1,000 notifications per day? Are we better entertained? Are we better informed?

Several of us long-term investors have backed private companies including Bytedance in China, Daily Hunt in India and Epic Games, the US firm behind Fortnite. The latter’s Unreal Engine’s 3D-environment creation tool provides the technology to make the metaverse that we see in science fiction films a reality.

But we are equally looking at services that foster better communication and community development, business models that are moving away from ad-based revenue streams, and platforms that make better use of our time rather than driving online addiction.

MasterClass is one such private company. The subscription service combines education with entertainment to offer captivating learning experiences featuring some of the world’s masters of their crafts and state-of-the-art produced video content.

Polarisation and Nationalism

After a couple of decades of building global supply chains, ‘walls’ are being erected again and national policy will likely dictate manufacturing and distribution priorities. We need to factor in this to our investment decisions.

Take, for instance, the recent struggles of the automotive industry. It has faced semiconductor shortages that were further aggravated by Covid and the occasional Suez Canal closing. The result has been lower production volumes, delivery delays and higher car prices.

Semiconductors, among other sectors, have become a matter of national security. In a US context, it is likely to drive reshoring of fabrication plants. But this is easier said than done when 80 per cent of all semiconductors are manufactured in Asia.

Similarly in a China context, the government is top-down aggressively pushing for the development of a domestic semiconductor industry that will make the country less dependent on foreign innovation and imports.

Along these lines, we have invested in UK-based Graphcore, which designs its ‘intelligence processing unit’ (IPU) chips to optimise performance around natural language processing and machine vision use cases.

We have also taken a stake in Beijing-based Horizon Robotics, which designs chips and software for autonomous driving vehicles. Both compete with NVIDIA’s graphics processing units (GPUs).

In China, consumer goods are another expression of increasing national pride driving an investment opportunity. Homegrown brands are building products bottom-up to cater to local consumer’s needs and tastes. This contrasts with the way multinational corporations have tried to localise their existing products for the China market.

The days of the KFC restaurant being the ‘coolest’ location in a Chinese Tier Two or Tier Three city are gone.

And remember that we are talking about a market of 1.4 billion people, many of whom enjoy increased spending power.

Last year, we invested in a Chinese beverages company called Jiangxiaobai, which has launched its own brands. It’s laser-focused on the country’s younger population. It’s a vertically-integrated company, owning and operating everything from the farms where the ingredients are cultivated, all the way to wholesale and direct-to-consumer distribution.

Exciting Sectors

Now that we have looked at some of the underlying issues, let’s talk about some of the technologies addressing them, and the investment opportunities that arise from private companies deploying them.

Electric Vehicles

The expected EV revolution will be highly dependent on the ‘upstream’ sourcing of supplies of raw materials and third-party electronic components, as well as advances in battery technology development.

How will North America and Europe compete when the largest manufacturers of battery cells in the world are all Chinese, South Korean and Japanese companies?

Or when key battery materials including lithium and cobalt come predominantly from places such as Bolivia and Congo respectively, before they are shipped to China for refining? These substances have travelled on average 50,000 miles by land and sea before they arrive in the form of battery packs in car factories.

Europe’s answer is currently being built in Sweden by Northvolt. It will manufacture battery cells that should satisfy much of Volkswagen and other European car makers’ demand over the coming years.

As to North America, we have recently backed Redwood Materials, a Nevada-based battery recycler. It’s a modern-day mining company, if you like, just with better margins and much less damage to the environment.

It takes less than 200 iPhones to recover the amount of cobalt needed for the battery of a Tesla Model Y. Redwood recovers more than 95 per cent of the lithium, copper, nickel, and cobalt contained in existing cells. The company was founded by Tesla’s former chief technology officer JB Straubel, so he knows a thing or two about batteries.

We have also seen promising developments in battery chemistry by other American private and recently public companies. They include:

- Sila Nano’s work on anode materials

- Quantumscape’s solid state battery technology

- Proterra’s work on battery packs and battery management systems for heavy-duty use cases

Batteries and electric powertrains are also likely to transform transportation by air, at least for shorter distances, for people and goods alike. We are shareholders in the electric aircraft firms Joby Aviation, Lilium and Zipline.

These companies have intensive research and development efforts underway and plan to spend substantial sums on fixed assets over their early years. They will need a considerable amount of time before they can launch their services at scale and start returning capital to shareholders. So they are not every investor’s ‘cup of tea’.

But they belong to a very sparsely populated peer group, have huge potential for growth, and could become nationally or regionally critical.

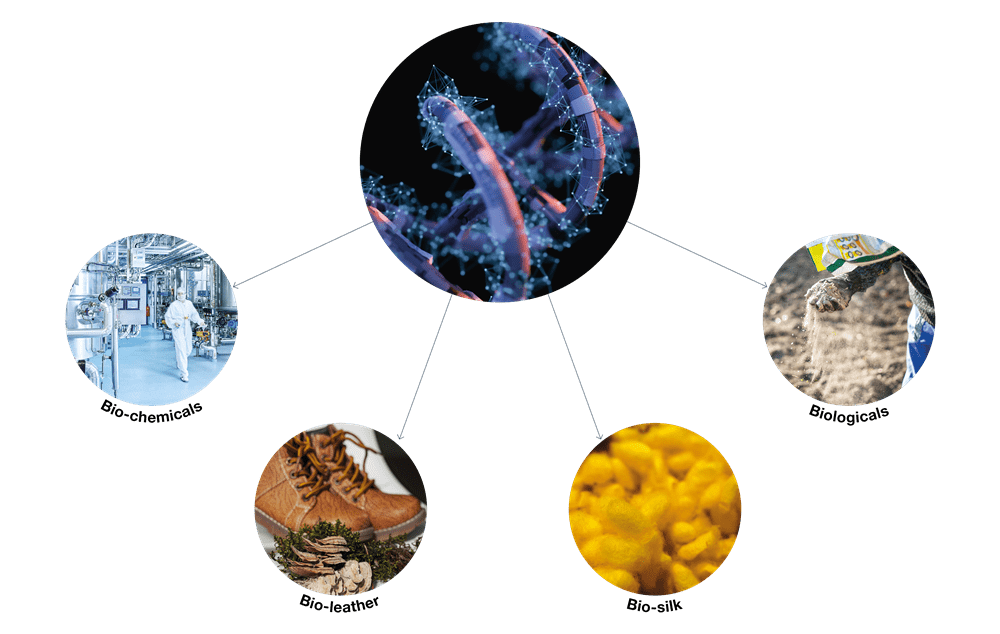

Synthetic Biology

Synthetic biology companies use genetically modified microorganisms to produce proteins that give rise to novel material properties and industrial processes.

Genentech pioneered the space when it found a way to make insulin using E coli bacteria. The method was commercialised in the 1980s, in partnership with Eli Lilly.

But the unlocking effect only came about in more recent years when the cost of gene sequencing began declining rapidly, in parallel with production operations becoming more efficient.

Ginkgo Bioworks is a prime example of a platform company involved in industrial synthetic biology. Rather than working on applications itself, Ginkgo seeks to drive down the time and cost of making the microorganisms that make the proteins.

We have also researched and invested in companies that bio-fabricate silk fibres and leather without killing animals. As an additional benefit, they can design the mechanical properties and aesthetics to meet their customers’ requirements.

Perhaps even more excitingly, synthetic biology can also be used to dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of traditional industries, such as chemicals.

To make chemicals you need a lot of heat to get the necessary reactions. This is normally achieved by burning fossil fuels. But nature makes amazing catalysts in the form of enzymes, which need much less heat. These are complex molecules that have been historically difficult to make and even harder to programme. But Texas-based Solugen, in which we have invested, has found ways to precisely do that.

Other companies are disrupting additional sectors with similar processes, including Pivot Bio in agriculture. It has transformed the way biological fertilisers are produced and applied, with zero waste and zero environmental footprint. Isn’t that something?

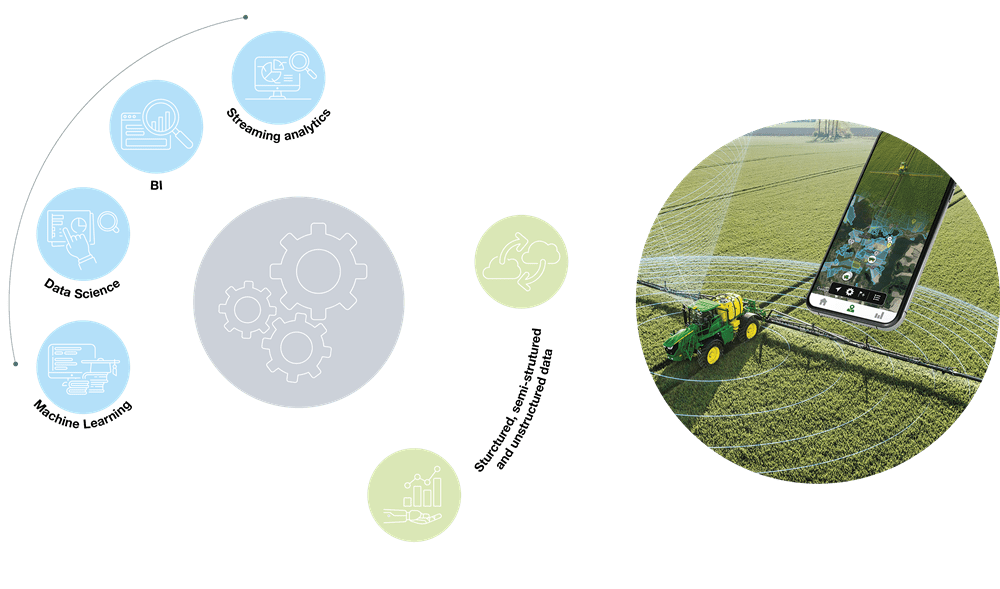

Data Science and Machine Learning

No, we aren’t going to call this section AI, because the moment we do, our minds will drift to humanoid robots and other aspects of artificial general intelligence that still belong to the realm of fiction, and require breakthroughs – such as quantum computing – before they can materialise.

Instead, we’re talking about technology that’s already behind daily experiences, such as our Google searches, our Amazon and Netflix recommendations, facial recognition scans that unlock our phones and authorise purchases, and so on.

To date, only a small number of large tech companies have had the privilege of being able to provide these product experiences and derive the associated economic benefits. They sit on proprietary data sets, having recruited the very best of the world’s top talent, and create their own ‘tech stacks’ – interconnected tools, software libraries, databases and frameworks used to power apps and websites.

In contrast, companies from other sectors have struggled in this field, despite having amassed their own data.

This is about to change because Snowflake and Databricks, among other companies, have created infrastructure-as-a-service platforms that offer data science and machine learning tools via the cloud. They enable anyone to join the ride, essentially democratising these technologies.

Agricultural equipment maker John Deere, for example, has embedded sensors in its machines for years. It can now deploy algorithms that affect pretty much every line on its profit and loss statement. This is an immensely powerful force for change.

People’s Needs

We’re also looking at the flip side of the coin: companies that support jobs where either the human soul or the dexterity of our hands cannot be currently replicated by technology.

These predominantly involve people in blue-collar posts in services that haven’t yet been wiped out by the internet. These are also jobs of the future, to which we all need to pay more attention.

One example is WorkRise, which, as already mentioned, is active in the energy industry. Another is Honor, a company placing care professionals in the homes of senior citizens, offering a range of services to beloved elderly family members. This is a sector that will grow in the coming years, as most societies are aging.

The Right Approach

The brief tour of part of our crystal ball is complete. But we would be amiss not to describe how we see investing in private companies as an asset class, and what we think is the right approach.

The best investors have always sought to provide long-term capital to truly exceptional businesses, allowing their clients’ assets to compound over time. That has not changed. What has changed over the last 10 years is the way these companies capitalise themselves. They are staying private for longer. The average age of a private company at IPO has doubled over the last two decades and now stands at 11 years.

Today the combined capitalisation of all private companies valued over $1bn – so-called unicorns – is about $2tn. That’s pretty much at the level of the aggregate market cap of the S&P mid-cap index. It’s a big and growing asset class.

There’s a variety of reasons. The increasing availability of capital makes it easier to raise money privately. Regulation has also made it more burdensome to be public.

But, as we are discovering in our own interactions with founders, we believe the most important factor is a cultural shift in these entrepreneurs’ perception of what it means to be private versus public.

Founders realise that they can be more focused, and by extension gain competitive advantage, by having a tight-knit group of private shareholders and keeping their companies out of the public markets’ spotlight.

All else being equal, they can build better businesses by staying private longer.

This has two consequences for public market investors. The first is by the time they get to buy in, more growth has passed. To state the obvious, every doubling of the value of a business that happens while it is still private is a doubling that’s lost to public investors.

Second, and more significantly, the public markets are unable to learn about the future these companies are creating. As companies stay private longer, this blind spot is bigger than it has ever been. It has got to the stage where we would argue you cannot understand the public markets unless you understand the private markets. In our view the only way to rectify this is by being an active investor in private companies.

Having said that, you cannot simply turn up one day and start investing in the world’s best private companies.

Private markets are not democratic. Private companies get to choose which investors they speak to and then who gets to become a shareholder, a partner on the journey of building their business.

At Baillie Gifford we are fortunate to be such a partner. And by gaining access to these private businesses, we have a window into the future.

What is our approach, you may ask.

Patience is critical. A company striving to do something difficult that will take a long time obviously has a greater chance of success if it has a long-term patient shareholder base than if it has shareholders looking to maximise profit quarter-over-quarter with their time horizon limited to between four to five years.

We have a role to play in helping our private and public companies succeed by being that long-term patient voice, while encouraging other shareholders to think likewise.

What the founders of these late-stage private companies really need is investors who embrace risk, support innovation, invest over multiple funding rounds and encourage them to lay the foundations of future success, well beyond the IPO. This is the definition of being a stage-appropriate investor.

We also believe that the opportunity set is truly global and sector agnostic. We measure companies’ growth prospects relative to one another, across different fields and without geographical quotas in our portfolios.

We are global investors and generalists. We find it intriguing to see the future emerge in one country, before it is transplanted to another. We try to avoid sector-focused biases.

Let us then conclude by saying that investing in private companies is not a passive game. We nearly always put primary capital into a business, in contrast to public markets where shares are normally bought from other investors.

It is particularly meaningful when that capital we invest on behalf of our clients also helps to solve humanity’s most critical issues. Because then we are not only learning about tomorrow’s world but also playing an active role in shaping it.