Even though the banking sector’s troubles are unlikely to give way to an intense credit crunch, the global economy won’t emerge unscathed.

Asset allocation: crunch won't trigger big rate cuts

Aggressive monetary tightening from the US Federal Reserve and other major central banks has triggered turmoil in parts of the banking industry, inviting comparisons with the global credit crunch that upended financial markets 15 years ago.

We believe fears of a 2008-like financial crisis are overblown. Nevertheless, the economic convulsions resulting from bank closures in the US and the state-aided takeover of Credit Suisse in Europe will soon become apparent: global GDP growth will be slower and below its long-term potential over the rest of this year.

For all this, investors seem to be getting ahead of themselves in expecting the Fed to begin cutting interest rates by as soon as July. Like other central banks, the Fed’s hands are tied – high inflation will prevent it from providing monetary stimulus in the coming months even if it sees fit to introduce other short-term measures to ease strains in the banking system.

The overly dovish scenario discounted by fixed income markets is one reason why we have downgraded bonds to benchmark weight. It’s a tactical move. Yields on shorter-dated government bonds have fallen too far, too fast. Cash moves up to overweight as a result.

Our expectations for a renewed bout of economic weakness, meanwhile, mean we remain underweight equities. Not only will stocks’ price-earnings multiples struggle to expand but corporate earnings also look set to stagnate as business conditions worsen.

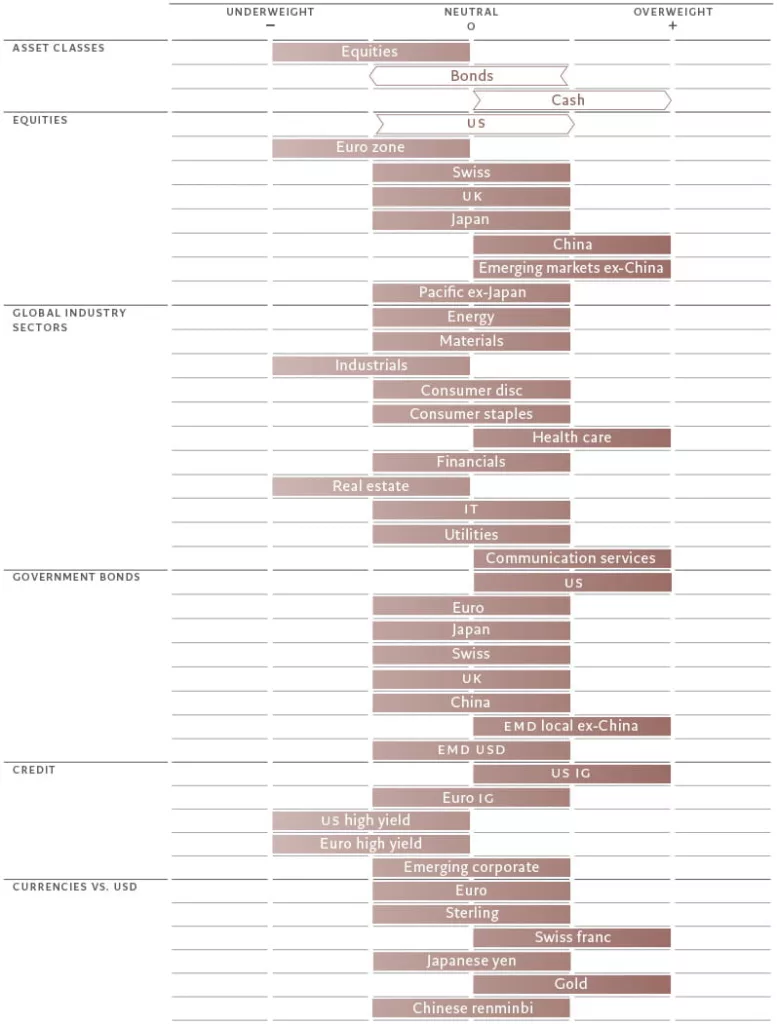

Fig. 1 – Monthly asset allocation grid

April 2023

Our business cycle readings show the banking crunch will weigh on economic growth over the medium term. GDP growth among advanced economies is on track to slow to 1 per cent this year from 2.7 per cent last year.

In the US, recent financial turmoil could prompt small to medium-sized banks – responsible for a third of total lending in the country – to tighten their credit standards, which in turn would weigh on consumption and business investment.

These lenders are likely to remain vulnerable as savers with an estimated USD8 billion of uninsured deposits could yet park this cash with larger, safer banks or seek other assets to secure higher yields, creating further losses on regional banks’ balance sheets.

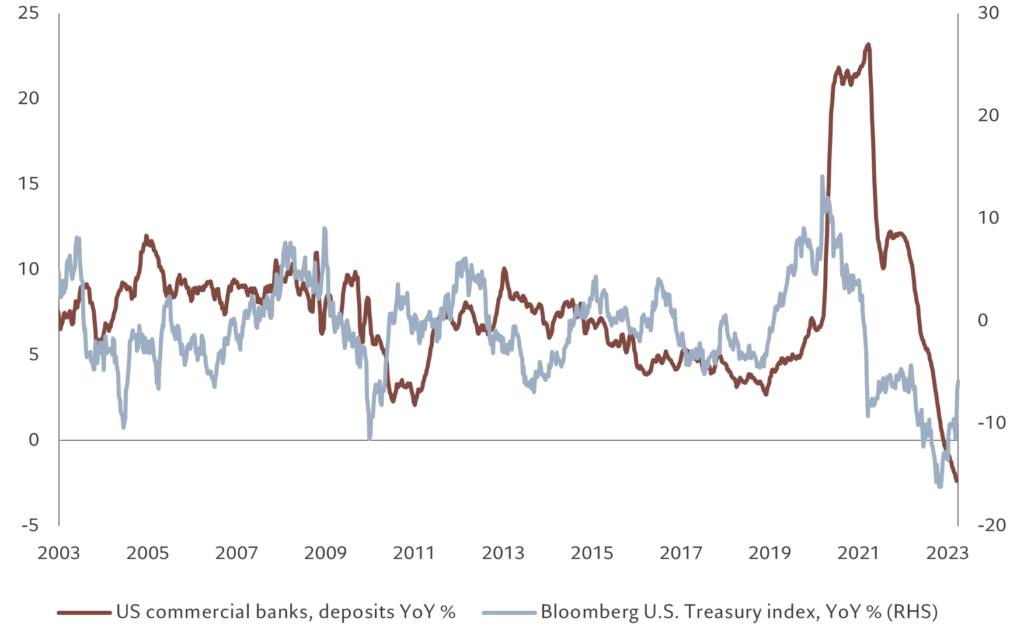

Fig. 2 Liquidity mismatch

US commercial banks deposits and US Treasuries index, year-on-year change in %

But there is a reasonable possibility the US economy could avoid a recession.

The country’s households still have USD1.5 trillion of excess savings, while the Fed has provided backstops to prevent more banks from collapsing. Much depends on how resilient consumer and business sentiment prove to be in the face of ongoing turmoil among reginal banks.

The outlook for Europe is not especially positive either, but the region’s financial sector is likely to hold up better than its US counterpart given European banks’ plumper capital and liquidity cushions.

That said, credit conditions are expected to become even tighter as the European Central Bank raises interest rates to tame stubbornly strong price pressures, which should weigh on risky assets.

A bright spot within the global economy is emerging markets, where growth is likely to accelerate to 3.2 per cent this year, led by China, which is enjoying a strong bounce from its post-Covid reopening.

We are also encouraged by signs that Beijing’s regulatory crackdown on corporations is easing, which could brighten prospects for the country’s stocks and bonds.

Declining inflation and recent dollar weakness also bode well for emerging market economies.

Our liquidity model presents a mixed picture. The Fed was quick to respond to the banking crisis, rolling out an emergency lending programme to banks through which it provided liquidity totalling some USD400 billion.

This has had a quantitative easing-like impact on markets, increasing what we consider to be the fair value of S&P 500 index, boosting liquidity-sensitive and growth-oriented equities and trimming yields on longer-maturity bonds.

Given persistent inflationary pressure and resilience of the economy, however, our models suggest that market expectations for Fed rate cuts of as much as 100 basis points this year and a further 100 basis points by 2024 look very unrealistic.

A key indication from our valuation framework shows bonds are less attractive after problems in the banking sector precipitated a sharp drop in yields.

All other assets are trading at fair valuations.

When it comes to profit forecasts, model implies near flat corporate earnings growth globally in 2023. Emerging markets remain the most dynamic region. Here, we expect company profits to grow over 11 per cent this year, significantly more optimistic than the consensus view, which is for a mild contraction.

Our technical indicators provide conflicting signals. With money market funds attracting inflows of some USD340 billion in the recent four-week period, the largest outside of the Covid crisis, it would be tempting to view this as a defensive shift.

The inflow, equivalent to 10 per cent of US money market fund assets, mirrored a flight from bank deposits. Counteracting that signal, however, outflows from equities were limited as redemptions from US stocks were offset by inflows into emerging markets equity funds.

Equities regions and sectors: America Inc looking up

Expectations that the Fed might soon halt interest rate hikes and a resulting sharp drop in US bond yields took pressure off growth-oriented equity markets and sectors in March, boosting technology and US stocks in particular. We believe this market dynamic could remain in place for some time. US equities’ sectoral composition – especially the dominance of tech firms – should offer investors protection from further weakness in economic growth. For this reason, we have upgraded US equities to neutral from underweight.

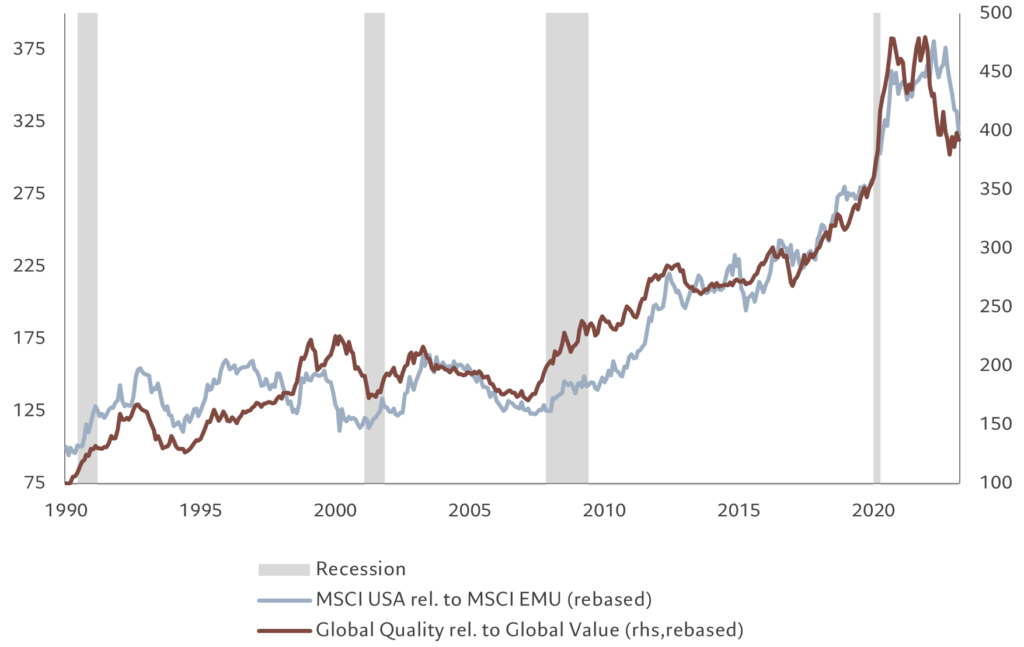

Tech and communications services make up a large proportion of the US equity market, which offers investors exposure to quality growth factors that should outperform at this point of the economic cycle (see Fig. 3).1 With official interest rates close to their peak, even if the market is wrong in looking for significant rate cuts later in the year, quality growth stocks should still fare well. Given that the US stocks make up 70 per cent of MSCI’s global quality index as against the US’s 60 per cent weight in the global equity index, that suggests US equities should prove resilient in the coming months.

Fig. 3 – Quality to beats value

MSCI USA performance relative to MSCI EMU; Global Quality performance relative to Global Value. Both indexes rebased.

At the same time, analysts have in recent months cut their expectations for US corporate earnings growth and profit margins in the face of monetary policy headwinds but have not done the same for European companies. To us, this is a sign that forecasts for US companies are overly pessimistic.

That’s not to say US small caps won’t struggle – regional banks – those institutions revealed as being most vulnerable to the effects of past interest hikes – are a major source of funding for small and medium-sized companies. But overall, we’re less pessimistic about the outlook for the US economy than consensus – we expect the US economy to weather the financial ructions better than in the past, especially with the Fed inclined to provide the system with emergency liquidity.

While the US market merits an upgrade, we have begun to question the Japanese equity market’s prospects given its heavy weighting towards cyclical sectors and in light of the fact that the Bank of Japan looks poised to abandon its ultra-easy monetary stance. Dropping its yield curve control policy – through which it targets a specific yield range for long-term bonds – is likely to push up short-dated Japanese bond yields, dampening the outlook for its export-oriented companies at a time when demand from other developed economies is already set to slow down. For now, we maintain our neutral weight on Japanese equities.

More broadly, we are forecasting global corporate earnings to remain largely flat during 2023, with emerging markets and especially China being the exception. In those markets, we see the potential for earnings to outstrip consensus forecasts. We expect emerging market earnings to rise a touch above 10 per cent this year, against a consensus view that they’ll be flat, and compared to just 2 per cent growth for developed market equities. Moreover, these economies are further ahead on controlling inflation and in some cases have become more stimulative. Portfolio flows into emerging market equities have in recent weeks offset outflows from the US market. We remain positive on emerging equities and China in particular, and are overweight both.

Fixed income and currencies: beware high yield

Heighted aversion to risk, the threat of recession, weaker corporate earnings prospects. Recent developments do not augur well for riskier bonds. They also strengthen our conviction in our underweight stance on high yield credit. Yield spreads on sub-investment grade debt may have widened a little in the face of banking sector turmoil but valuations still do not fully reflect the increased risk of defaults. The sharp tightening of lending conditions is not fully reflected in what investors currently receive in compensation for taking on credit risk – the Fed’s loan survey is consistent with US high yield spreads of double the current levels of 475 basis points.

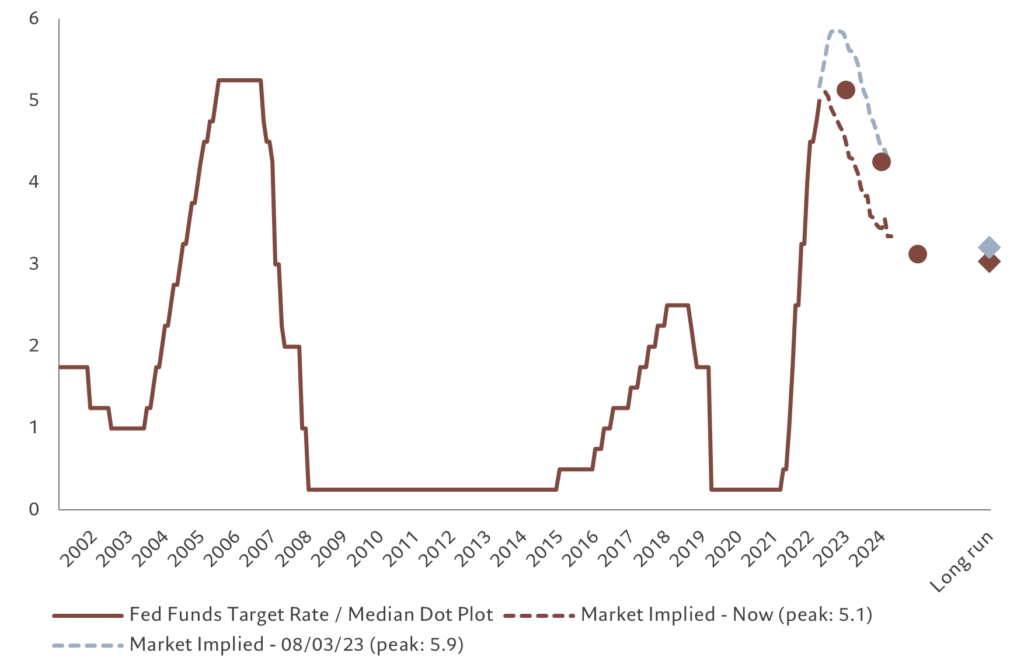

Elsewhere in the fixed income market the situation is more nuanced. Take US Treasuries. Yields here have fallen sharply as markets have rushed to price in the prospect of aggressive interest rate cuts from the Fed to shore up the financial sector (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 – Expectations vs reality

Fed funds rate and market expectations

We would argue they have been too hasty. Inflationary pressures have yet to fade and we think that markets are now too optimistic about how rapidly interest rates will be cut. The cut currently being priced in by July is highly unlikely to materialise.

If we are right, yields will have to go back up. Crucially, however, that should only really affect the shorter end of the Treasury yield curve. Yields on longer-dated bonds end are an entirely different matter. They will either hold firm or fall as economic conditions worsen.

We thus remain overweight Treasuries. Particularly because European government bonds look unappealing by comparison.

The ECB is more hawkish than the Fed. And we agree it needs to be because inflation dynamics in the euro zone are much more worrying with core inflation not yet having peaked. What is also true is that the ECB can afford to take a more aggressive stance because the problems plaguing the US banking system are less of a concern for Europe given its more stringent regulatory framework.

In Japan, too, there are some tentative signs of a more hawkish tone emerging from monetary policymakers. There is growing pressure on the Bank of Japan to pivot away from ultra-easy monetary policy, not least in dropping its yield curve control measures, which would allow rates to rise. However, we believe this shift is some months away and thus remain neutral on JGBs for now.

Emerging market local currency bonds continue to offer attractive investment opportunities, thanks to strong economic growth outlook (particularly in Asia) and easing inflationary pressures. The economic growth gap between emerging and developed economies is set to widen, which usually augurs well for emerging market assets. And any weakness in the US dollar could provide an additional source of returns, primarily by way of currency appreciation for a host of developing world currencies.

We hedge our risk exposure with long positions in the Swiss franc and in gold.

Global markets overview: banks suffer

March was a turbulent month. The demise of Silicon Valley Bank – which specialised in lending money to tech start-ups – sent tremors through financial markets in the US and beyond. Several other regional US lenders felt the aftershocks. On the other side of the Atlantic, Credit Suisse also wobbled, prompting a state-orchestrated takeover.

The KWB Bank Index, which tracks the performance of leading US regional banks, lost nearly 30 per cent of its value before recovery slightly (see Fig. 5). More broadly, financials were the worst performing equity sector, finishing the month down some 6.5 per cent in local currency terms. Real estate stocks also suffered intense pressure, as did small-cap companies.

Fig. 5 – Bank pain

KWB* regional bank price index, reindexed

Conversely, communication services and technology stocks ended sharply higher, each gaining around 9 per cent supported by a sharp decline in bond yields and by their exposure to “quality” characteristics.

Global bond yields moved sharply lower as investors bet that central banks would soon turn to looser monetary policy in order to counter rising recession risks and support financial stability.

Yields on 10-year Treasury bonds broke below 3.45 per cent while those on shorter-dated notes fell even more steeply. The yield spread between 10-year and 2-year Treasuries recorded its sharpest narrowing (dis-inversion) since October 2008, moving from -114 basis points to -47bps.

Elsewhere, emerging market debt held up well, supported by the re-opening of the Chinese economy and improved confidence in China’s housing sector.

The weaker dollar provided an additional boost for emerging market assets. The greenback weakened by 2 per cent against a trade-weighted basket of currencies.

Oil lost 5 per cent on concerns that the banking crisis could hit economic growth more broadly, leading to reduced demand. Gold, meanwhile, benefitted from increased risk aversion, with prices rising to USD2,000 per ounce. Our models suggest current pricing of gold points to a further 10 per cent fall in the dollar.

In brief