In this episode of Behind the Markets, we had the pleasure of speaking with Professor Dr. Wim Schoutens from the University of Leuven in Belgium. Professor Schoutens has a wide range of expertise, including such areas as Financial Mathematics, Cryptocurrencies and Blockchain, Machine Learning, and more. He is also an independent expert advisor to the European Commission.

The focus of our discussion with Professor Schoutens was on the recent happenings in the Contingent Convertible (CoCo) bond market, especially considering the takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS at the behest of Swiss regulators, as well as the write down of roughly $17 billion of CoCo bond issuance. Many global investors are seeking to understand whether this was truly a ‘one-off’ situation, or if they need to incorporate into their forecasts the possibility that governments or regulators may have a more flexible interpretation of certain rules in future crises.

Professor Schoutens indicated that, after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09, he was involved in discussions on ways to possibly reform certain parts of the financial system. It was clear to him that regulators were thinking about a new kind of instrument. Their motivation was to better protect taxpayers in case of another, future financial crisis. Interestingly, the Swiss were at the forefront of this thinking and they came up with a regulation that basically introduced CoCos to the market.

At that point, coming out of the Global Financial Crisis, if Switzerland was taking an action, then others would look to follow suit. Professor Schoutens was investigating the possibility of a security that ultimately looked like the CoCo bond and he was among the first to write papers and books on the topic.

Now, a CoCo is in the category of security that we think of as a ‘hybrid’, meaning that it is not exactly equity, and it is not exactly a bond—it has characteristics of each. For instance, typical bonds will have a date of maturity, i.e., a 10-Year bond matures in 10-Years and the principal is paid back to the bond holder. A CoCo, like an equity security, has no such maturity date and is often referenced as ‘perpetual.’ But there are coupon payments and Professor Schoutens, along with his PhD students, were seeking to develop some pricing models to better think about managing the risk of these types of securities.

Now, the current situation relating to Credit Suisse received a lot of attention because banks and real companies in general have a capital structure. Usually, equity holders are at the bottom, meaning that they have a lot of opportunities for upside in good times but, on the other hand, they must be ready to take the biggest share of the losses on the downside. Many investors think about this hierarchy of different securities when making investments, especially in certain styles of fixed income investments like distressed debt.

There is no dispute that, in a depiction of the capital structure of Credit Suisse, the CoCo bonds were higher than the equity. However, what surprised many, is that the CoCo bonds were written down to a value of $0, while the equity securities maintained at least some value. Many would have expected that, before the CoCo bonds would be written down to $0 the value of Credit Suisse equity would have also been written down to $0.

Professor Schoutens indicated that certain provisions that would have allowed for this would have been in the small print of the contract and, in his view, should not be possible in the other parts of the European market beyond Switzerland.

It was clear that European regulators outside of Switzerland were not happy with this because it turns around the logical balance sheet structure, where equity holders take the first losses and have the highest risk. Professor Schoutens also noted that even in Belgian newspapers—and he noted that Belgium is far from a major global financial hub—opinions were indicating that Switzerland can no longer be trusted because their government and regulators have upended the essential rules of finance and ordering of risk within the capital structure.

It looks like there could be court cases coming on this matter, brought by global bond investors and other large asset managers, so we will have to see what types of settlements are or are not achieved or if other important precedents are set from a legal standpoint.

Professor Schoutens did indicate that in his view although European banks are well capitalised, there could be contagion as a result of the Credit Suisse debaucle. In his opinion, it cannot be ignored that the perception of Credit Suisse from a profitability and risk management perspective was not great, and, there may be added pressure on Deutsche Bank, another case where the reputation for risk management has not been pristine.

Professor Schoutens noted that part of the discussion around Credit Suisse included some large shareholders becoming more reticent to increase their equity positions. In his view, with some of these banks that have had questionable reputations in recent years, it is difficult to attract new equity investment.

Another discussion important for banks in 2023 regards the fact that we have—in most jurisdictions—exited the ‘zero interest rate’ world. Savings accounts and checking deposits, at least in theory, should no longer be associated with zero interest rates. Deposit holders may see the interest rate available on other types of very low risk accounts, and they may tend to hold lower and lower balances at banks if they seek to maximize some of these interest rates that they can get with relatively low risk.

Professor Schoutens, at least so far, recognises that this is a behavioural force present in the markets today, but he does not currently see evidence or indications that Europeans will tend to move away from banks and toward other types of low-risk accounts in droves, but this could change in the future. What’s more important is how easy it has become to electronically move money from one account to another. The look and feel of a ‘bank run’ or a ‘loss of confidence’ is totally different. The speed with which a bank could go from ‘ok’ status to ‘defunct’ status is probably faster than at any point in history.

Finally, since Professor Schoutens was involved in some of the early modelling and valuation studies of CoCo bonds, we discussed what he sees today. It is clear that yields are high, but risk is also high. If, week by week, we are seeing different ‘runs’ on European banks, then there could be greater and greater concerns around CoCo bonds. However, if the tone of the market changes and we are able to get beyond the more immediate concerns and the fact that banks look well capitalised is better recognised, then the forward-looking returns from these levels of yield could be attractive—we note that these securities certainly have unique risks as well as sensitivities to European regulators that other securities may not have.

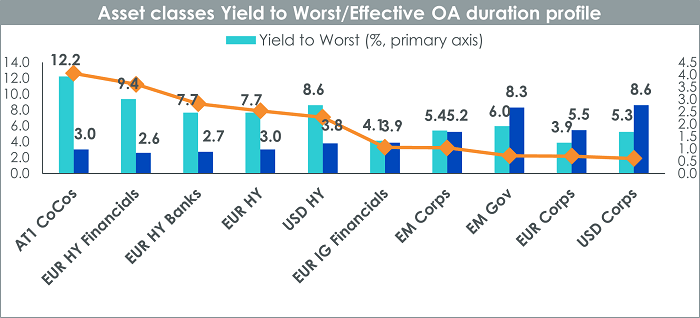

In Figure 1, we see a measure of risk/return in different parts of the financial ecosystem—shown here through duration and yield-to-worst figures. We note that duration is not the sole risk that CoCo face—if there is a European banking crisis, we’d expect to see some issues in these securities. However, if we can get past some of the immediate concerns, current yield levels tell us that the securities are also pricing in significant risks.

Figure 1: Current Snapshot of Different Yield and Duration Statistics

Source: WisdomTree, Markit. Data as of 23 Mar 2023. Yield is yield to worst (YTW) and is based on the duration-adjusted market value weighting. Effective OA duration is effective option-adjusted duration. AT1 CoCos is the iBoxx Contingent Convertible Liquid Developed Europe AT1 Index, USD HY is the iBoxx USD Liquid High Yield Index, EUR HY is the iBoxx EUR Liquid High Yield Index, USD Corps is the iBoxx USD Liquid Investment Grade Index, EUR Corps is the iBoxx Euro Liquid Corporates Index, EUR IG Financials is the iBoxx EUR Liquid Financials Index, EUR HY Financials is the iBoxx EUR Liquid High Yield Financials Index, EUR HY Banks is the iBoxx EUR High Yield Banks Index, EM Corps is the iBoxx USD Liquid Asia ex-Japan Corporates Large Cap Investment Grade Index, EM Gov is the iBoxx USD Liquid Emerging Markets Sovereigns Index.

You cannot invest directly in an index.

Historical performance is not an indication of future performance and any investments may go down in value.

To listen to the discussion, please click here or search for ‘Behind the Markets’ on any podcast player.