The risk of stagflation makes life much more difficult for governments and central banks and the heightened risk of policy mistakes is likely to keep volatility high in bond markets. But investment opportunities are also opening up.

The UK has been in the firing line lately. But while some of its travails are self-inflicted, all developed market economies are essentially in the same boat when it comes to stagflation. And both central banks and governments are struggling to find a way forward.

Decades of countercyclical monetary policy have left central banks’ balance sheets bloated and government budgets stretched. This has resulted in situations where economies are ever less able at the margins to absorb big shocks. Unforeseen events were manageable during the previous era of low growth and low inflation – or outright deflation. In an environment where central banks didn’t have to worry about price stability, they could stimulate economies with fresh infusions of liquidity as and when needed. But now that’s changed.

Inflation hamstrings policymakers. With consumer prices rising at a rate four times and more above their target, central banks can no longer use their toolkits to stimulate economies even as they start to weaken. Their first responsibility is to return to price stability, which means shrinking their balance sheets and raising interest rates. Until they are certain that they can return inflation to 2 per cent – in most cases – their monetary instruments are bound to cause pain, as US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell made clear.

The big risk for investors is that the Fed and others now over-tighten in much the same way that they kept policy overly loose in years past. Given that much of central banks’ power to influence longer dated interest rates, and therefore the economy, is down to their credibility, they have been reluctant to admit to past policy errors. They’ve argued that it was impossible to anticipate the full effects of their decisions given the scale of economic shocks, such as Covid, and the uncertainty about their outcomes. Only in hindsight is it possible to tell that they were wrong in being over-stimulative, they argue. As a result, they are likely to err in the opposite direction now, so as not to give the impression that they will always take a dovish stance. Political pressure adds to the mix – politicians are worried about how voters will react at the next elections to the erosion in their living standards.

Governments, meanwhile, are struggling to devise policies that shore up growth and protect their most vulnerable citizens – those most at risk from inflation eroding their purchasing power – without stoking further price pressures. Here, the risk of policy error is also high, as British Prime Minister Liz Truss’ recently made very clear by launching an extreme tax cutting programme without regard for what that would do to public sector debt and thereby triggering a rout in the UK bond market.

All of this has prompted central bankers to alter their decision functions.

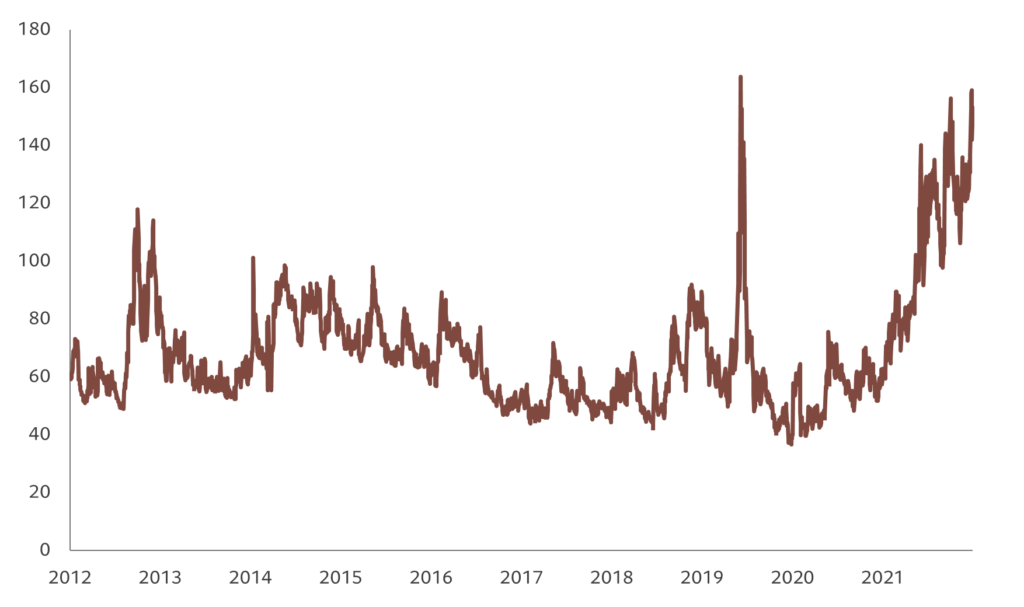

Fig 1 – MOVEing higher

Merrill Lynch MOVE index of bond market volatility

Given that interest rate rises act with a significant lag, we have yet to see the consequences of central banks’ tightening measures so far. The danger for economies now is that central banks go too far. But given their starting point – the current tightening cycle began with zero or even negative policy rates – policymakers are likely to believe that there’s more risk in not tightening enough than in doing too much.

The hard truth, however, is that economies need inflation to erode the value of the huge private- and public-sector debt loads that have built up over the past decade or two. Realpolitik means that central banks might well have to accept higher inflation than their target commits them to. This could mean changing their remit or, more likely, turning a blind eye to inflationary overshoots, so long as they’re not large.

Meanwhile, central banks are likely to make a natural progression to adopting digital currencies, which will help them target stimulus much more precisely and effectively and open the doors to other unconventional policy tools. For now, though, they’re stuck with the blunt tools they already have.

A result of this mix of policy constraints, shifts in central bankers’ reaction functions, and the fact that policymakers won’t be able to keep interest rates supressed at historic lows, markets are likely to face yet more volatility. Market fluctuations we’ve seen during recent months are likely to become the norm, not least in fixed income. (See Fig. 1 – MOVE index)

The weak spots for fixed income right now centre on higher inflation, lower growth and much lower market liquidity. On the other hand, there has been such severe repricing right across the fixed income universe that many bonds – sovereign and credit, developed and emerging market – are starting to look like good value. Crucially breakeven duration rates are increasingly compensating investors for volatility. Even at the riskier end of the credit market, classes of contingent convertible bonds now look attractive, with high single or even double digit yields and relatively low cash prices, which leave investors with less downside risk and greater prospects of above-average returns. Over time, these sorts of opportunities will likely leave investors with attractive annualised returns. Unlike 12 months ago where investors were were getting bond like returns for equity like risk now the opposite is true: they are getting equity like forward looking returns for bond like risks.

The world is certainly a more complicated place than it was on the eve of the Covid pandemic. And policymakers – both central banks and governments – are struggling to find the right course, between inflation, high levels of debt and events that bring with them great uncertainty – like the war in Ukraine. The bond market is bound to suffer significant volatility. But attractive opportunities are starting to arise for investors, not least in those areas where credit where spreads have widened significantly.