2024 marked the fourth consecutive year of rising US yields, for the first time since the early 80’s. We have been patient in recent years going overweight duration in our multi-asset portfolios as we have persistently viewed the risks to US nominal growth relative to consensus expectations as skewed to the upside.

But as we enter 2025, the market is pricing a Federal Reserve that is nearly at the end of its easing campaign at a time when the risks to consensus growth expectations are now more balanced than they have been this cycle. Moreover, we think the net effect of policies from the incoming administration is likely to be less inflationary than current discourse suggests. Overall, the risk-reward for duration has improved, and we look to add government bond and selective credit exposure on dips.

January macro and asset class views

Highlights

- After four straight years of higher US 10-year yields, we now enter 2025 viewing duration as attractive.

- The risks to consensus expectations on growth and inflation are no longer clearly skewed to the upside, right when the market has priced out a significant degree of easing from the Fed.

- The incoming administration’s policies are likely to be less inflationary and the Fed’s reaction function to tariffs less hawkish than the current discourse suggests.

- We like stocks and bonds going into 2025, while using selective long US dollar exposure to hedge against a further hawkish repricing of the Fed or significant rise in tariffs.

2024 marked the fourth consecutive year of rising US yields, for the first time since the early 80’s. We have been patient in recent years going overweight duration in our multi-asset portfolios as we have persistently viewed the risks to US nominal growth relative to consensus expectations as skewed to the upside.

But as we enter 2025, the market is pricing a Federal Reserve that is nearly at the end of its easing campaign at a time when the risks to consensus growth expectations are now more balanced than they have been this cycle. Moreover, we think the net effect of policies from the incoming administration is likely to be less inflationary than current discourse suggests. Overall, the risk-reward for duration has improved, and we look to add government bond and selective credit exposure on dips.

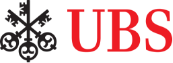

A different set up

Consensus economist growth expectations in 2023 and 2024 were much lower than what the economy ended up delivering (Exhibit 1). The combination of strong private sector balance sheets, robust income growth supporting consumption (including a boom in immigration) and extended support from fiscal policy all supported growth despite the sharp rise in interest rates in 2022-2023. But now consensus has caught up, expecting 2.2% real GDP growth this year. While we believe positive real incomes and resilient consumption may continue to support growth above this number, the room for upside vs. expectations has lessened considerably.

Exhibit 1: Economists have significantly underestimated growth, until now

Annual US Real GDP Growth

The chart shows large differences between expected and realized real GDP growth, with 2025 being nearly three percentages points higher in 2023 and 1.5 percentage points higher in 2024. The expected growth figure for 2025 is a shade over 2%.

And while we see a recession this year as quite unlikely, the economy doesn’t look as hot as it has in previous years. The labor market is still cooling as indicated by the household survey and a broad set of indicators (quits, openings, continuing claims, etc.), even though headline payroll data has been strong. Residential activity continues to struggle amid elevated mortgage rates, and business spending has also weakened. This data does not suggest an abrupt sharp slowing of the economy is likely, but it does suggest rates at current levels may still be restrictive.

In the meantime, we believe the underlying trend of inflation is lower, excluding potential one-off effects from tariffs. While upside surprises for core PCE in September and October show the path towards 2% will remain bumpy, the November print annualized under 2% and, in particular, added to evidence that shelter prices are on a decelerating path. The three-month moving average of core PCE stands at 2.5%, hardly booming, and ongoing cooling in shelter and wages suggest further progress towards the 2% target this year.

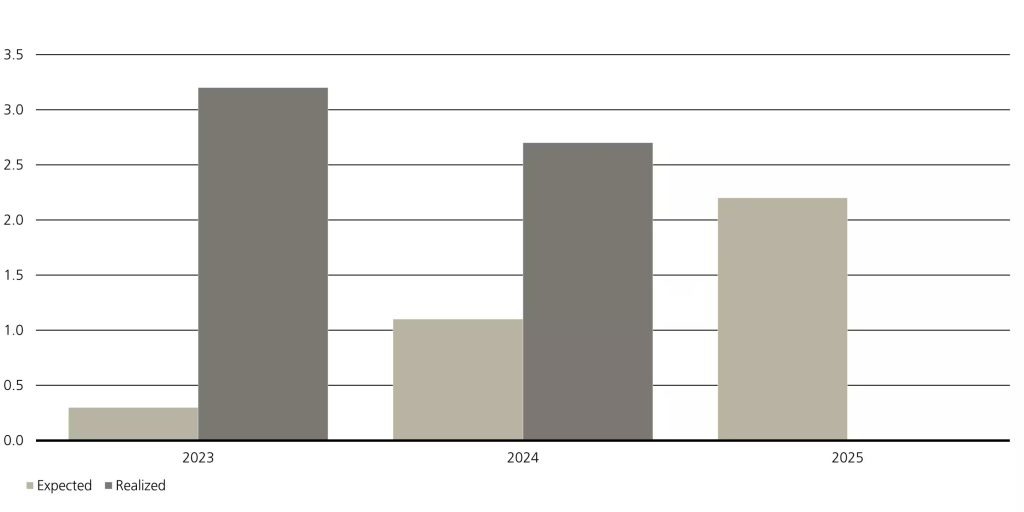

Exhibit 2: Yields have continued to rise despite disappointing economic data of late

US Treasury 10-year vs. Citigroup US Economic Surprise Index

The line chart shows the US Treasury 10-year benchmark mapped against the Citi Surprise index from September to the end of December 2024. After tracking together closely through September, October and November, the positive relationship breaks down and they become negatively correlated.

The Fed, tariffs and immigration

This more balanced outlook for growth and inflation comes at a time when the rates market has moved in a more hawkish direction. US 10-year yields rose 100 basis points since the Fed started its easing cycle with a 50 basis point cut in September. Immediately following that meeting, there were still 10 (25 bps) cuts priced through 2025. Two cuts were delivered in November and December respectively, but the market is now pricing in just 1-2 more in 2025 before an extended pause.

To be sure, the Fed has moved in a hawkish direction as well, with the December Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) Summary of Economic Projections shifting from four to two cuts in 2025, broadly matching the market for this year. But the Fed still projects a couple of more cuts in 2026, and Chair Powell emphasized that he still views policy as ‘meaningfully restrictive.’

Importantly, the Fed upwardly revised its core PCE forecast to 2.5% from 2.2% this year. This shift in expectations was partially due to the bump in inflation in September and October, but some members have also started to include the effects of policies from the new administration into their framework and projections.

Ex-tariffs, a 2.5% core PCE forecast is conservative given the disinflationary pressures mentioned above. And while there is a great deal of uncertainty on President-elect Donald Trump’s trade policies this year, we are not convinced that a significant tariff increase would be met with a meaningfully hawkish shift from the Fed, for three reasons.

First, while tariffs raise inflation, they should be looked at more as a one-off shift in the price level as opposed to a repeatable inflationary force. As long as inflation expectations remain contained, which we expect they would, then the Fed should look through the supply shock, all else being equal. Second, tariffs don’t just raise prices, they weaken growth. As the Fed has a dual mandate, they should be sensitive to the potential impacts on employment. Finally, and related to the prior two points, the 2018 tariff episode contributed to a sharp drop in risk assets and tightening in financial conditions, leading the Fed to ultimately move in a dovish, not hawkish direction.

A separate potential negative supply shock is the new administration’s focus on curbing immigration, which has been commonly cited as a potential source of inflation. To be sure, net immigration flows are already falling quickly and the uncertainty is more around the scale of deportations under President Trump, including the logistics around such actions.

Mass deportations could tighten the labor market through slowing labor force growth and result in higher wages. However, the slower population growth would also depress demand. As the surge in immigration was a boost to growth in recent years, it is reasonable to assume that a reversal would be negative. The Fed would likely be patient in reviewing labor market data before jumping to conclusions. But as of now we do not see tighter immigration policy leading to tighter monetary policy.

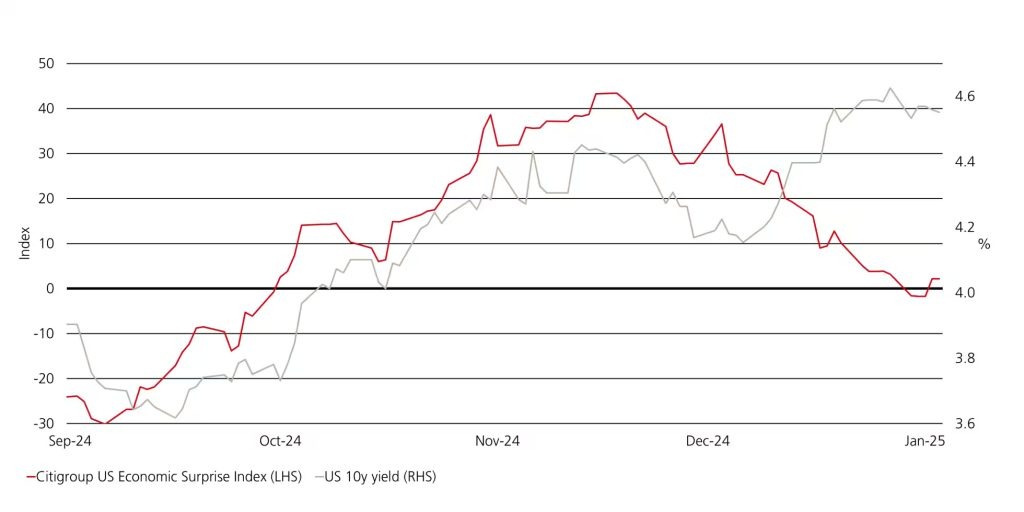

Current pricing of the terminal rate is at 3.9% (two-year forward overnight index swap (OIS) rate) against the Fed’s upwardly revised long run ‘dot plot’ (the Fed’s Summary of Economic Expectations) of 3%. While there is still likely further upside to the Fed’s estimate of ‘neutral,’ we think the risks to the near 4% market-implied terminal rate is skewed to the downside.

Exhibit 3: The market’s implied estimate of the Fed’s terminal rate is well above the Fed’s own projection

Market Pricing vs. Central Tendency of Long Run Dot Plot

The line chart plots two variables – the FOMC long Run Dot Plot and market pricing of the 2-year Forward policy Expectations as measured by 2-year one-month OIS. It runs from January 2023 to December 2024 and shows three brief periods of alignment – January 2023, April 2023 and October 2024. An approximate 1% difference has opened up, with current pricing being higher (as with all other periods of discrepancy).

Fiscal risks are more nuanced

Beyond tariff and immigration risks, Trump’s fiscal agenda has also raised concerns on inflation and directly increasing risk premia on bonds. We are less concerned.

First, we think Trump’s team will operate with some sensitivity to inflation and the impact of their policies on lending and mortgage rates. Indeed, inflation and the high cost of living consistently appeared in polls as a top concern for US households, which was likely a key factor in Trump winning the election. Essentially, Trump’s current ‘mandate’ is for less, not more inflation, unlike in 2016 when it was ‘growth at all costs’. Incoming Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent has commented on such factors, and argued his focus on tax reform, deregulation and increasing energy production can result in noninflationary growth.

Second, with respect to the risk of fiscal expansion leading to inflation, we think there will be more resistance to an expanding fiscal deficit. Bessent has already outlined a plan to lower the budget deficit to 3% of GDP by 2028 by focusing on discretionary spending cuts. The formation of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is aimed at reducing the size of the federal government apparatus via a combination of staff reductions, reducing fraud and waste and cutting unneeded programs.

While the willingness and ability to enact significant cuts in non-defense discretionary spending is debatable, the focus on the issue is a good start. If all else fails, a Red Sweep does not give the Trump administration free reign on fiscal spending, as demonstrated by House Republicans recently rejecting Trump’s request to raise the debt ceiling ahead of his inauguration.

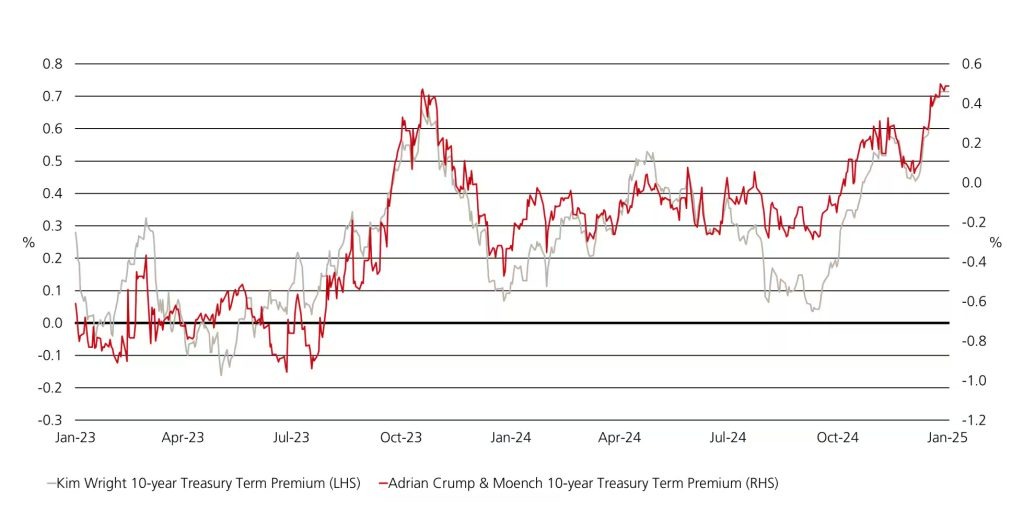

Meanwhile, longer-dated Treasury yields have moved to a level that we see as providing some compensation for these fiscal and inflation risks. The yield curve has steepened thanks in part to increases in measures of term premia – the additional compensation investors required to bear the inflation and fiscal risks, amongst others, in holding duration. These measures have increased recently and are at levels not seen since 2011 at the 10-year point of the curve.

The last time they were around these levels was in October of 2023, after the Treasury announced an increase of USD 770 billion (~2.5% of GDP) in Treasury bond issuance for 2024 in August, catalyzing a rapid bond sell off. In contrast, the additional issuance that would be incurred by the tax cuts would pale in comparison, particularly if the tax cuts are being at least partially funded. Moreover, inflation was significantly higher, and the unemployment rate was still below 4% in October of 2023 – it made more sense for term premia to be higher back then.

Exhibit 4: Term premia has risen to the October ’23 highs

Measures of 10-year Treasury Term Premia

The line chart shows two variables – the Kim Wright 10-year Treasury Term Premium and the Adrian Crump & Moerich 10-year Treasury Term Premium – plotted together from January 2023 to December 2024. They closely track each other.

Asset Allocation

We like stocks and bonds to kick off 2025. While equities are not cheap, we still think decent growth, healthy earnings, disinflation and ongoing global monetary easing are powerful tailwinds that should underpin risk asset performance. US Treasuries remain our primary hedge for risk assets against downside surprises in growth, and at current yields are now attractive in their own right. With US corporate bond spreads historically narrow, credit is more for carry than price appreciation; all-in yields remain attractive.

The key risk to our asset allocation is a potential shift higher in the stock-bond correlation, driven by concerns of accelerating inflation and/or a more hawkish Fed. We are carefully managing these risks in our portfolio construction, including via foreign exchange where selective long USD positions against EUR and CNH should perform on a hawkish repricing of the Fed (as well as tariff escalation). Widening concerns on US deficits would conceivably lead to a weaker USD, but we have yet to see any evidence of a breakdown in correlation between US yield differentials with peers and the greenback. We are monitoring this risk closely and have the means to flexibly respond should these dynamics shift.

Asset class views

The chart below shows the views of our Asset Allocation team on overall asset class attractiveness as of 3 January 2025. The colored circles provide our overall signal for global equities, rates, and credit. The rest of the ratings pertain to the relative attractiveness of certain regions within the asset classes of equities, bonds, credit and currencies. Because the Asset Class Views table does not include all asset classes, the net overall signal may be somewhat negative or positive.