Inflation has dominated the conversation in 2022. What can we conclude from the final raft of meetings this year – and from the year as a whole?

In their final meetings of 2022, the US Federal Reserve (Fed), European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of England all maintained their programmes of hikes to base rates.

Although all three have slowed the pace of hikes, increasing by 50 basis points (bps) rather than 75bps, the messaging was consistent. More hikes are likely ahead, and very possibly more than market participants have been pricing in – especially from the Fed and ECB.

Why the hawkish tone?

The ECB was bold in its communication, stating “interest rates will still have to rise significantly at a steady pace to reach levels that are sufficiently restrictive”. And given it was just a few months ago that the ECB divorced itself from forward guidance, ECB President Christine Lagarde was surprisingly forthright in implying 50bps hikes “for a period of time” and that markets were not sufficiently pricing in further hikes.

The ECB also dropped any reference to the cumulative tightening delivered so far – which was taken to be a dovish statement at the last meeting – and has dramatically revised up its inflation projections. This is despite most of the indicators moving in the other direction: the euro is stronger, gas and electricity prices are lower, yields are higher, and financial conditions are generally tighter. It would appear strong wage growth is the main driver for this change.

At the same time, in parsing the Bank of England’s communication, we can conclude that inflation, wages and activity have all been higher than policymakers expected. The bank’s communications reiterated its commitment to acting “forcefully” if necessary.

Comparing global central banks

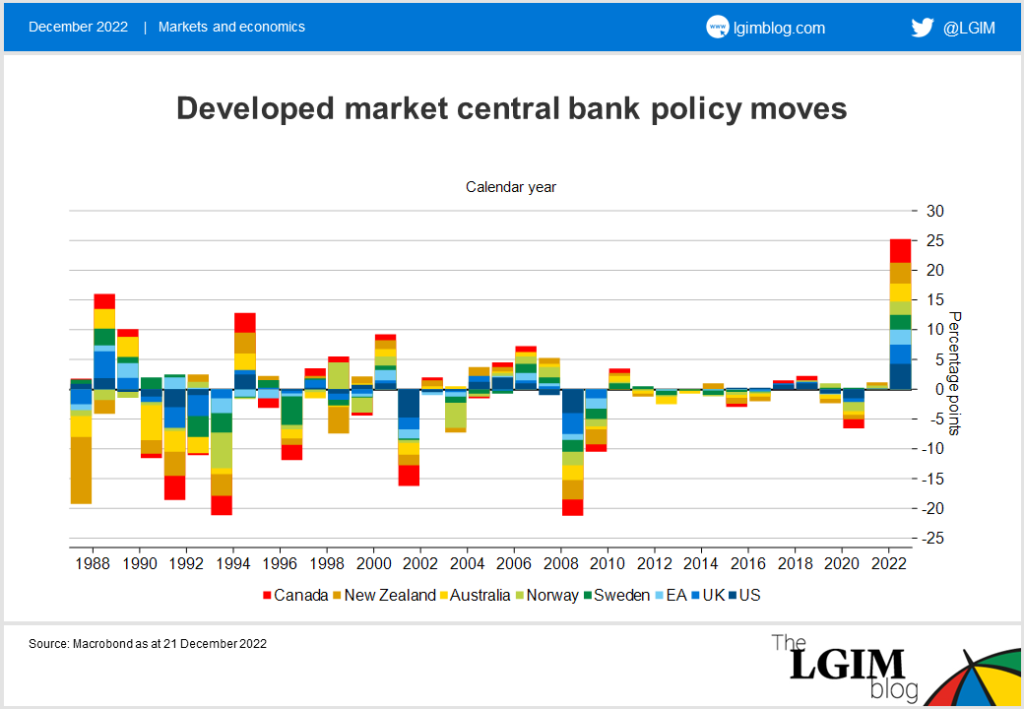

Meanwhile, 2022 has seen the most synchronised interest rate tightening for at least 35 years.

The word ‘unprecedented’ has been overused in recent years, but it’s clear that 2022 has been an outlier in terms of monetary policy action.

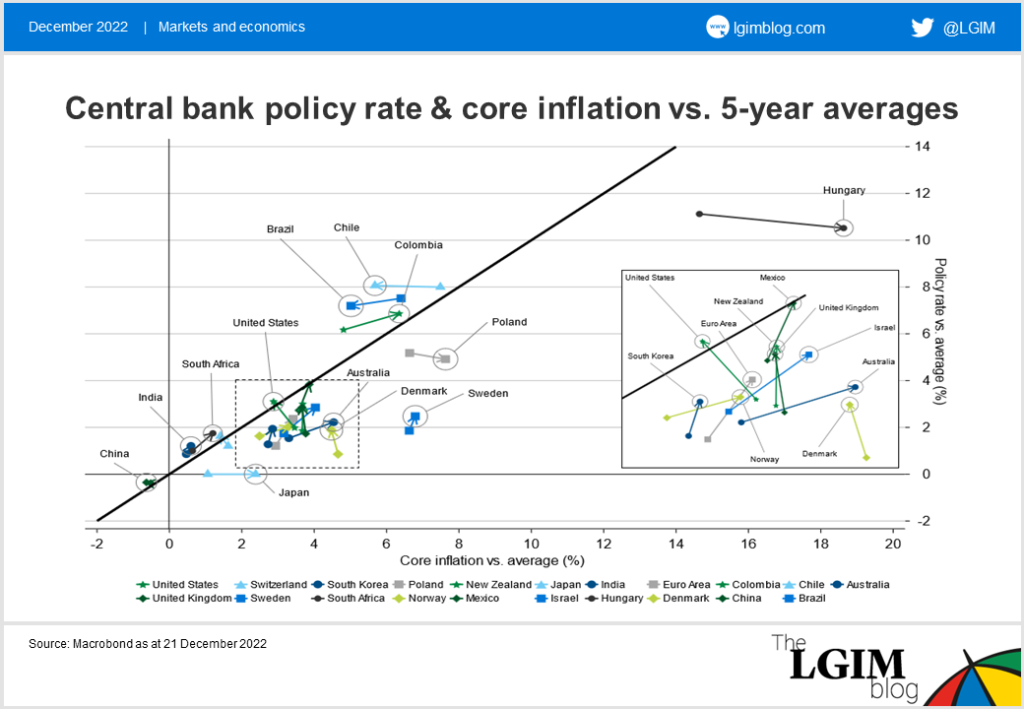

To take a step back and try to sort the signal from the noise, we looked at the policy stances of central banks on inflation compared with their five-year moving averages.

This is a complex chart, so let’s break it down:

- The forty-five degree line acts as a threshold to delineate between central banks that have allowed real rates to deviate above or below their five-year moving average

- A central bank whose country marker remains close to or on the line has managed to maintain real rate positions relative to their five-year moving average

- Any country marker below and moving towards the threshold (as indicated by the direction of the arrows over the previous three months) has tolerated a drop in real rates but is now tightening policy in an attempt to move these back to their five-year moving average

What have we learned?

A small portion of central banks reacted with swift policy responses.

For example, both Brazil and Chile are starting to see core inflation slowly subside and their central banks are now able to relax upward pressure on policy rates.

On the other hand, a tight-knit group of western central banks led by the Fed promoted a view that the surge in inflation was ‘transitory’ and that they could delay policy response until evidence suggested otherwise.

We are now seeing this group of central banks act in accordance with the traditional Taylor rule: i.e. trying to bring inflation under control by raising interest rates. In theory, pushing real rates closer to their pre-pandemic averages should act to moderate inflation.

US data show we are potentially witnessing the start of this inflation moderation; according to our chart, the US has now crossed above the threshold, making it a relative outlier in developed markets.

It’s not over yet

However, there remains a small subset of countries whose current situation elevates the risk of runaway inflation expectations. For example, central banks from Hungary, Poland and even Japan continue to let real rates fall further below their five-year averages, potentially stoking further inflation.

After the latest set of meetings, central banks seem committed to deliver the hikes market participants have priced for the first part of next year. But with many economies already in recession or heading towards one, this additional tightening runs the risk of exacerbating and forthcoming downturn.

However, economic weakness and rising unemployment should mean inflation is brought under control and could allow policy to begin to reverse course either towards the end of next year or in 2024.