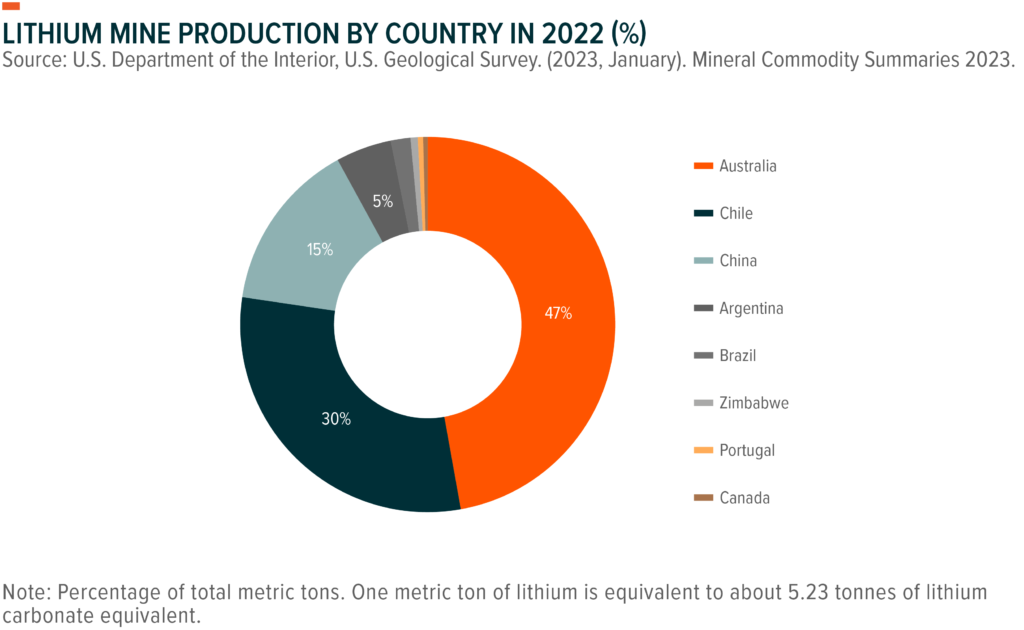

On April 20, Chile’s President Gabriel Boric asserted that he would move forward with plans to nationalise the country’s lithium industry. On the surface, Boric’s announcement would seem to represent a major escalation in government oversight that could compromise the prospects of operators in the region and affect the global lithium industry. Chile was second only to Australia in terms of lithium production in 2022 and boasts the world’s third largest lithium reserves at 9.6 million tons.1 However, Boric’s proposals fall well short of traditional nationalisation and likely do not represent an imminent risk to lithium miners in the region.

Key Takeaways

- President Boric campaigned on lithium nationalisation, but the implementation of this framework should not lead to full state control of lithium assets, especially in the short term.

- Operations could continue more or less unhindered for the major miners in the region, namely SQM and Albemarle.

- New regulations complicate the outlook for new Chilean lithium contracts in the coming decades, although they could also encourage the state to bring more output to the global marketplace.

Boric’s Plan Does Not Call for Immediate Control of Lithium Companies

Lithium nationalisation was a key talking point during President Boric’s 2021 campaign, and last week’s national address should not have come as a surprise to the market. The initiative is likely to pass Chilean Congress in the second half of 2023, but revisions are probable. Boric’s left-wing Social Convergence party does not hold a majority in Congress, which has already presented obstacles to the president’s agenda. There is also uncertainty regarding the long-term implementation of the policy. The balance in the Chilean government could shift dramatically over the next several years, especially with the next general election looming in 2025. It remains to be seen if an opposition party would be interested in maintaining the same lithium strategy.

Boric’s plan calls for the formation of a “National Lithium Company” to control Chile’s lithium operations and would require new lithium contracts to be issued through a public-private partnership. The most significant revelation from the president’s address is that the state would need to own at least 51% of any new lithium contract through these public-private joint venture structures.2

Notably, contracts for SQM and Albemarle, the primary miners of Chilean lithium and two of the largest lithium miners in the world, are expected to be honored.3 SQM has a contract until 2030 and Albemarle’s runs through 2043.4 Barring a dramatic shift in Boric’s position, these companies should be able to continue to operate for the duration of their contracts without government ownership. Boric expressed a desire to negotiate with these miners to incorporate some degree of state ownership into existing contracts; however, it is likely that a mutual agreement would be required to do so.

Miners Have Time to Adjust to New Regulations

SQM and Albemarle are the most likely companies to undergo future operational changes due to these policy developments. However, because of the duration of current contracts and unique points of leverage, these miners could be fairly insulated from associated risks.

SQM is domiciled in Chile, and the company’s primary lithium producing project is the Atacama salt flat. The duration of SQM’s contract does give the miner time to hash out an agreement with government officials, however. Another key consideration is that Chinese lithium miner Tianqi holds a roughly 22% share of SQM.5 Chile is a major trading partner with China, especially on lithium resources, which means negotiations between SQM and Chile are likely to include Chinese representatives seeking a balanced outcome. Ultimately, SQM cashflows may be relatively unaffected in the short term and favourable conditions could be offered on renewal of contracts after 2030. In a statement following Boric’s address, SQM said that it was analysing the strategy delivered by the government and hoped the new regulations would “be able to boost lithium production expansion in Chile.”6

Albemarle also operates a project at the Atacama salt flat. The company’s La Negra operation, which is primarily supplied by output from the Atacama salt flat, accounts for 22–40% of the company’s lithium conversion capacity.7 Because 20 years remain before contract expiration, the impacts before 2043 are likely minimal. Albemarle asserted that Chile’s new lithium contract model would have “no material impact” on business and that the company was assured current contracts will be honored.8

New Policy Could Bring Benefits, But Many Questions Remain

In one sense, mandated government ownership is likely to render prospective projects in Chile less attractive to miners and could act as a barrier for industry growth. Extensive government regulation is a major reason why Argentina is forecast to overtake Chile’s lithium production by 2030.9 That said, reimagined state involvement could promote expanded capacity. Historically, when companies obtain contracts in Chile, the state’s lithium regulatory body assigns them quotas intended to mitigate environmental degradation. In our view, a scenario exists where increased government ownership of lithium assets could entice officials to boost capacity.

Uncertainty remains regarding how Boric’s plan is meant to unfold. For instance, it is not yet certain if Chile will compensate lithium miners for investments made in state-acquired lithium assets. Similarly, governance of the mandated joint ventures has not been fleshed out. Could the Chilean state choose to change which miner operates in the partnership? How would an acquisition price be set for stakes in a joint venture? Could a shift in SQM or Albemarle’s control affect the ownership structure?

It is also important to distinguish between the different layers of the lithium value chain. The new regulations seemingly target the extraction of raw lithium concentrates and not the conversion process that turns this input into a battery grade resource. This focus could allow a miner that is involved in a joint venture to sell lithium to itself downstream for refining. This scenario could lead to favourable terms of exchange, but it is too soon to assess whether regulation will be crafted to address such dynamics.

Conclusion: Lithium “Nationalisation” in Chile is Sensationalised

Market access to Chile’s lithium is important for the growth of the battery and electric vehicle space, and recent developments do complicate the path forward. However, the idea that Chile is outright nationalising the lithium industry distorts the likely outcome of these regulations. For now, industry participants, including SQM and Albemarle, appear well positioned to digest President Boric’s plans without significant operational ramifications.

This document is not intended to be, or does not constitute, investment research as defined by the Financial Conduct Authority

FOOTNOTES

1. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. (2023, January). Mineral Commodity Summaries 2023.

2. Bloomberg. (2023, April 20). Chile Unveils Public-Private Model to Share Vast Lithium Riches with Mining Industry.

3. Visual Capitalist. (2022, October 14). The World’s Top 10 Lithium Mining Companies

4. Bloomberg. (2023, April 20). Chile Unveils Public-Private Model to Share Vast Lithium Riches with Mining Industry.

5. SQM. (2023, March). Corporate Presentation.

6. SQM. (2023, April 21). SQM Comments on National Lithium Strategy Announcement.

7. S&P Global: Commodity Insights. (2022, August 04). Albemarle Eyes 200,000 mt Global Lithium Capacity by Year-End.

8. Reuters. (2023, April 21). Chile Bid to Boost State Control Over Lithium Spooks Investors.

9. Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. (2023, April 21). Chile Plans to Take Control of Lithium Mining via Public-Private Partnership