Rising defaults in China show that Beijing meant business when it pledged to retreat from the distorting effects of its implicit guarantee policy and deleverage the system by allowing bad companies to exit. The daunting task is to avoid contagion. Can Beijing pull it off orderly?

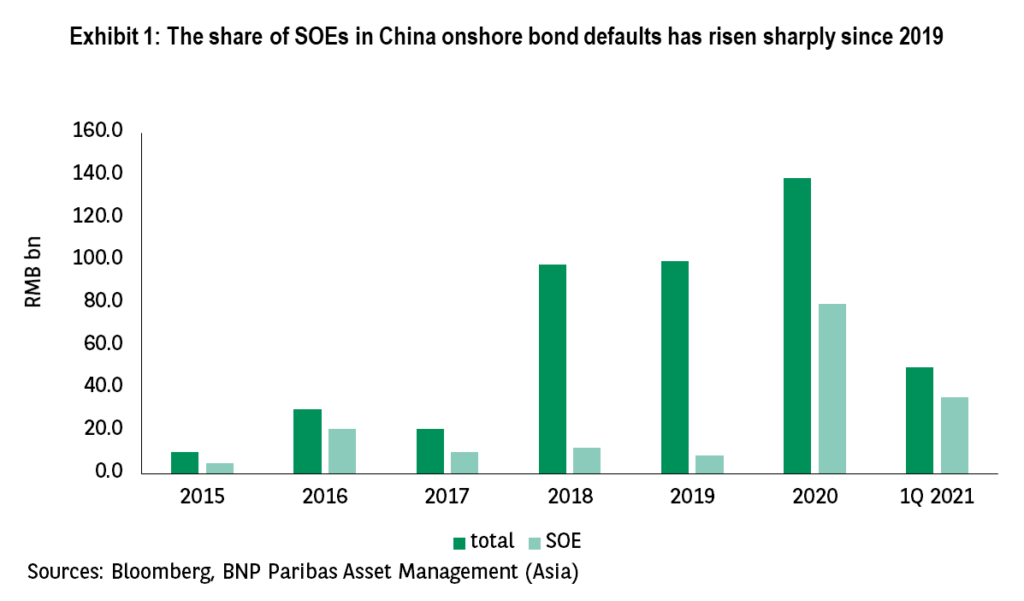

Bond defaults have been rising since the start of the deleveraging process in 2017. This has pushed up corporate bond spreads, kept them high and made them volatile. Defaults used to affect mostly private companies: They accounted for more than 80% of the total between 2017 and 2019.

However, the share of state-owned enterprise (SOE) defaults has climbed sharply since then (see exhibit 1), creating market jitters about the withdrawal of government guarantees leading to systemic instability. The recent concerns about the fate of an asset management company and a property giant have only added to the market anxiety.

Can Beijing Manage it Orderly?

Beijing has been signalling a gradual retreat from government guarantees on state firm liabilities since 2017. Regulators have become more explicit recently in their calls for SOEs to manage their risk or prepare to go bust]. They have reiterated that bond default risk should be diffused in an orderly manner. So, there is policy flexibility in the financial de-risking campaign to keep contagion at bay.

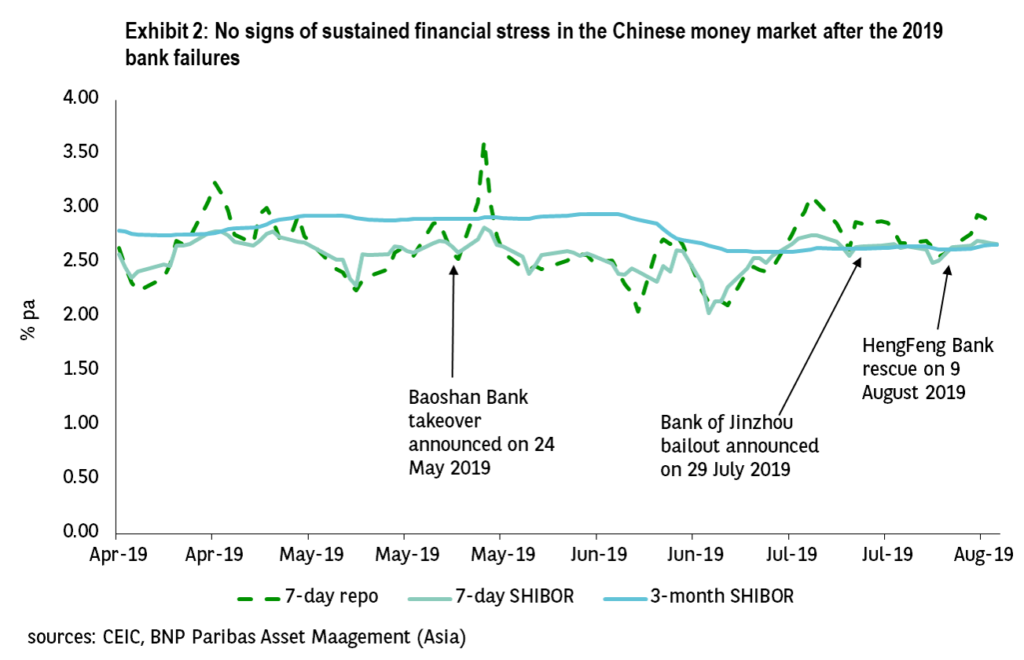

While the market worries that this is easier said than done, experience shows that Beijing has the tools and skills to prevent defaults from triggering systemic risk. The defaults of three Chinese banks between May and August 2019 raised fears about a systemic collapse, prompting speculators to bet on a banking crisis in China forcing a sharp repricing of risk.

However, the authorities rapidly and resolutely injected liquidity and put together resolution plans. This kept these bank failures from triggering any systemic risk (see exhibit 2).

Kicking the Implicit Guarantee Habit

The sharp rise in defaults shows China is serious about tackling the incentive problem in the system and that it can contain the contagion risk. There are two important implications:

1) The eventual ending of implicit guarantee is structurally positive for China’s credit/asset pricing.

2) The fears about contagion as government guarantees are withdrawn are, arguably, healthy. They show investors are responding to changing risks, which should help improve the market’s price discovery mechanism.

The implicit guarantee policy has distorted China’s credit pricing by keeping state firms’ financing cost artificially low, irrespective of their fundamentals. SOEs also received inflated credit ratings from local rating agencies. These ratings encouraged moral hazard and created a debt-laden state sector with zombie firms.

Thus, defaults could be a blessing in disguise by forcing state companies to adhere to hard budget constraints, exercise greater credit discipline and curb excessive investment. Crucially, more defaults will help reduce the state firms’ unfair advantage over foreign and private firms and improve capital allocation in China in the medium and long-term.

The credit rating environment is also changing. The big three foreign credit rating agencies, Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch Ratings, have been allowed to rate onshore Chinese bonds since 2019. Chinese corporations are increasingly seeking credit ratings from international agencies. This should help improve China’s credit rating quality.

Non-Systemic Companies have been Warned

Do not expect any quick changes. Government bailouts will likely continue for systemically important institutions, especially banks, and for those companies deemed strategically important. We should note that this is also the practice abroad.

Beijing will likely use a combination of state-led restructuring and market discipline to manage future corporate failures, as seen in its approach in handling the past credit events.

However, more bonds defaults can be expected to lead to ‘haircuts’ as they do in other markets. In the case of a bank failure in August 2019, the central bank did eventually step in, but it did not assume the assets at book value, as used to be the practice with bailouts. It only paid 30%. In another case, large creditors had to take up to 30% in losses.

All this shows Beijing’s determination to end the implicit guarantees and allow the market to discipline zombie firms. The government’s policy is to assess and deal with defaults on a case-by-case basis. Its backstop role for major firms still stands, but the guarantees for non-systemic firms, including their subsidiaries, are history.

Any views expressed here are those of the author as of the date of publication, are based on available information, and are subject to change without notice. Individual portfolio management teams may hold different views and may take different investment decisions for different clients. This document does not constitute investment advice.

The value of investments and the income they generate may go down as well as up and it is possible that investors will not recover their initial outlay. Past performance is no guarantee for future returns.

Investing in emerging markets, or specialized or restricted sectors is likely to be subject to a higher-than-average volatility due to a high degree of concentration, greater uncertainty because less information is available, there is less liquidity or due to greater sensitivity to changes in market conditions (social, political and economic conditions).

Some emerging markets offer less security than the majority of international developed markets. For this reason, services for portfolio transactions, liquidation and conservation on behalf of funds invested in emerging markets may carry greater risk.