We believe speculation in China’s housing market jeopardises GDP growth expectations and could break the historic link between Chinese stimulus and global asset prices.

Our base case is for Chinese GDP to grow 5.5% this year, despite weaker-than-expected activity recently. This assumes some policy easing and is based on moderate annualised growth of 4% over the remainder of 2023. However, the property sector poses a downside risk to this outlook.

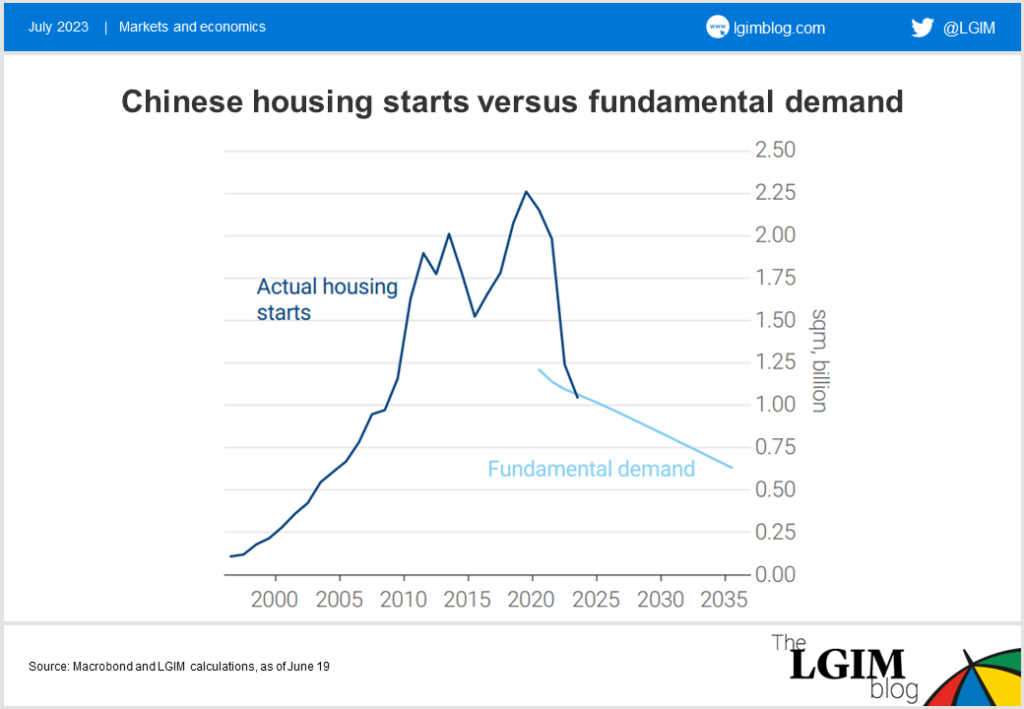

To assess how much more property activity needs to correct or whether it has already undershot, we estimate how much new housing or living space is needed per year. This is determined by annual rural-to-urban migration (as the new arrivals need to live somewhere), living space per capita, and the rate at which the existing housing stock depreciates.

It turns out that China needs to add about 1 billion square metres (sqm) of new urban living space per year (rural construction is negligible), at least for the next few years. Actual housing starts have fallen to about these levels, suggesting that there is not much upside to construction activity.

Hoarding houses

If anything, risks are to the downside as a closer look at the housing stock reveals. Subtracting cumulative housing sales from cumulative housing starts suggests that housing stocks are at normal levels of about two years of sales. It is the housing owned by Chinese households that looks excessive, in our view.

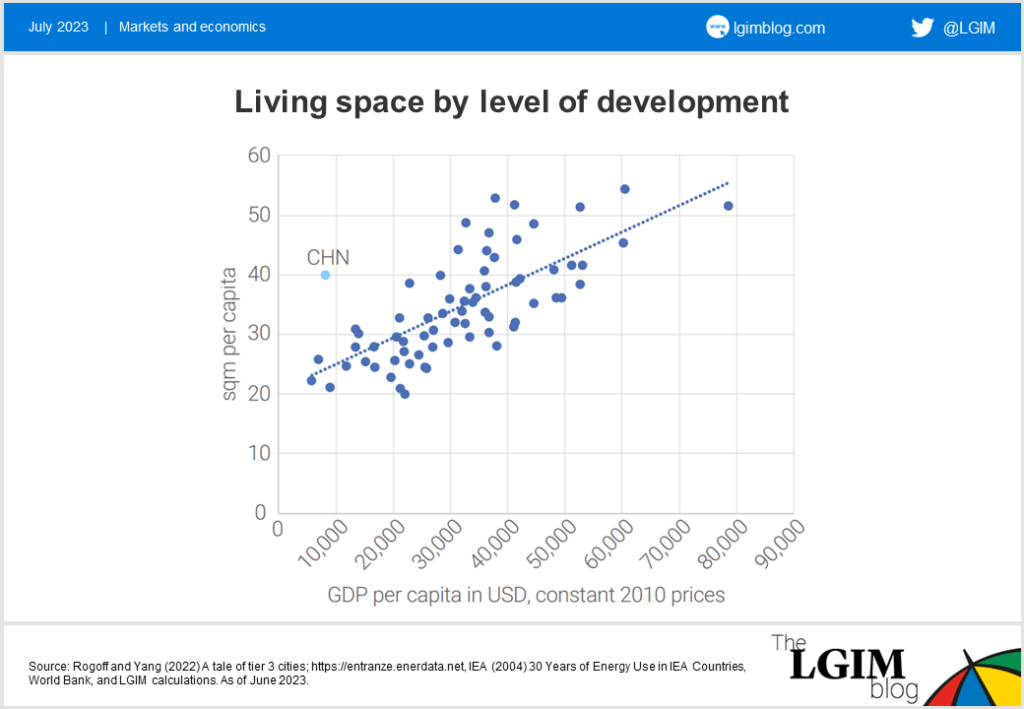

Living space per capita is around 40sqm in China – almost double what is normal at China’s level of development. If the excess stock were to come back onto the market it would take 13 years to clear, according to our estimates.

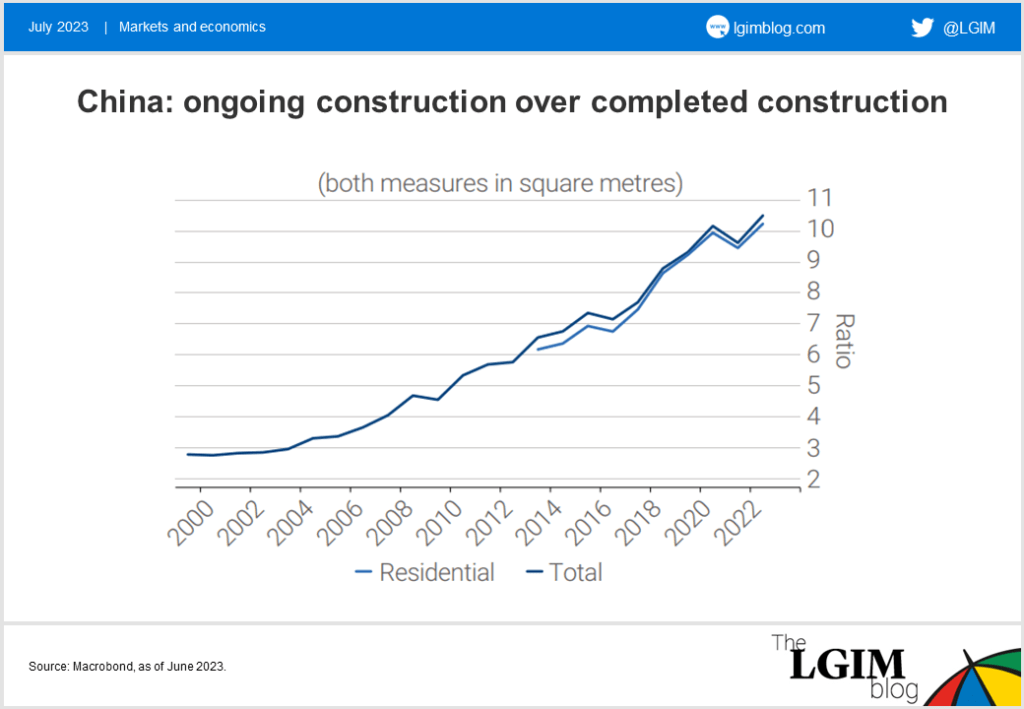

In addition, excesses are evident in housing currently under construction, which is 10 times the housing completed each year. Since it takes three years to complete a housing project, this ratio really should be three (where it was during 2000-2005). Since developers are pre-paid for construction, incentives are strong to take on ever more projects, particularly if other funding sources are being squeezed. This housing overhang would take another 3.5 years to clear, we believe.

Of course, it is not clear whether this housing overhang, mostly the result of speculative buying, will ever come back onto the market and, if so, over what period. But it definitely poses a downside risk to future construction activity.

What does this mean for commodities?

That subdued outlook for construction activity has a couple of implications. Most important for the rest of the world, the link between Chinese stimulus and global asset prices has historically flowed through commodity prices and commodity[1]exposed sectors.

That link is likely to be significantly weaker than has been true historically, and may even be broken with housing under structural pressure.

For Chinese assets, we think the combination of excessively bearish sentiment and stimulus expectations can drive a temporary rebound in performance at the current juncture, but that should not be mistaken for expectations of a sustained recovery.