The multi asset investor is at a crossroads. The direction they choose to take on addressing the transition to a low-carbon economy will not only impact their investment returns for decades to come but could change the course of the future of the planet. While climate matters may not shift the long-term return expectations of core asset classes over the next decade, it’s in the following decades that the investment (and real-world) impacts will be far more significantly felt. Failing to take the low carbon transition pathway now will result in far worse investment prospects in the 2030s and beyond. Investors would be leaving the next generation with a more challenging investment environment. Much more importantly, this would coincide with the legacy of potentially irreparable physical damage and more challenging living conditions for populations around the world.

Providing genuinely long-term capital to selected projects and technologies needed to make the transition will reap benefits not only over the next few years but also for the wider system in the long run. Making these types of investments today will mean a far greater chance of there being attractive investments available in a decade or two’s time. This is no time to be passive.

We recognise now is the time for action. Our long-term return expectations (LTRE) exercise has always been a key part of our investment process, and our climate-informed scenario analysis is being treated with the same due regard. The Baillie Gifford Multi Asset Team has undertaken an exercise to investigate and quantify the impact of different climate-related scenarios on the long-term return expectations of core asset classes. This involved blending climate and financial modelling techniques with informed assumptions to identify a focused range of possible pathways over the next 10 years and the very long term. The goal was to pinpoint which asset classes may be most sensitive to adverse financial shocks and which can support, and benefit from, the opportunities that lie ahead. This article summarises how the team went about the research and the outcomes of it.

Defining Possible Futures

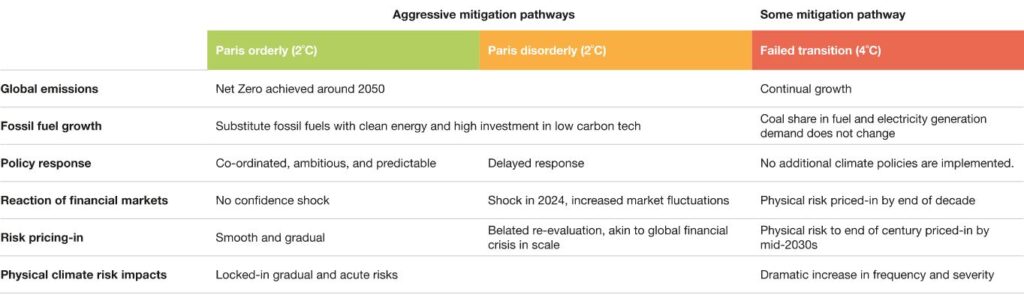

Our first step was to identify and define the scenarios that would form the basis of our assessment, which covers both a medium-term timeframe (10 years to 2030) and long-term timeframe (2030 to 2050). We enlisted the help of Ortec Finance, independent globally-recognised experts in providing measurable and research-backed financial metrics. They helped us define climate-related scenario narratives and to quantify the potential financial impacts on our key macro-economic input variables. We identified three representative climate pathways to assess. These, set out below, should be regarded as examples of plausible pathways, rather than future predictions or worst-case forecasts.

Key similarities and differences in our climate scenario pathways:

Orderly Transition: this scenario sees quick, coordinated, and predictable worldwide action to limit global average temperature rises to 2°C, which financial markets price in smoothly and gradually between now and 2024. The significant transition starts immediately, with high investment in low-carbon technology and technology take-up, ambitious low-carbon policy measures, substitution away from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources and biofuel, and negative emissions from carbon capture and/or afforestation and reforestation measures. With this immediate action, global emissions have already peaked and are already reducing but even if global warming is limited to 1.5°C, we will still experience locked-in physical climate impacts greater than today and will see impacts on growth that are less than under the Failed Transition scenario. This most closely corresponds to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body responsible for assessing the science related to climate change, aggressive mitigation scenario.

Disorderly Transition: this scenario results in the same real-world transition risks and opportunities, as well as the same locked-in gradual and acute physical risks, as the Orderly Transition. However, the reaction of financial markets is delayed until there is an abrupt realisation of the problem, perhaps triggered by a sudden physical event, or abrupt shift in global governance that allows for the deployment of a global policy response, which causes a confidence shock to the financial system in 2024. This is followed by a sharp write-down of assets – directly and indirectly related to carbon-intensive and related activities – in 2025, which is followed by increased market fluctuations and lower overall market confidence. The resulting systemic risk from belated pricing-in and the scale and speed of the required transition is comparable to last decade’s Global Financial Crisis. This most closely corresponds to the IPCC aggressive mitigation scenario; however, it differs from the Orderly scenario in the delayed global policy response and pricing-in of climate-related risks for carbon-intensive assets.

Failed Transition: although many countries are putting more low-carbon policies in place and renewable energy prices are falling significantly, a continuation of current policies will not be enough to limit global warming to 2°C in this scenario. No additional climate policies are implemented, and the global average temperature rises by 4°C by 2100 with a dramatic increase in frequency and severity of physical climate impacts. No further transition to a low-carbon economy takes place and the goals of the Paris Agreement, the international treaty on climate change adopted in 2015, are not reached. Differentiated regional policies and technological uptake lead to the Failed Transition pathway seeing continual growth in global emissions, not to mention the impact of disparate spending on adaptation and defence, leading to significant imbalances between regions and potential for a far less equal world. Physical risks are priced into the market by the end of this decade up to mid-century, and post-2050 physical impacts are priced in from the mid-2030s. This scenario most closely corresponds to the IPCC some mitigation scenario.

Integrating Climate Scenario Analysis into Our Long-Term Return Expectations (LTRE) Process

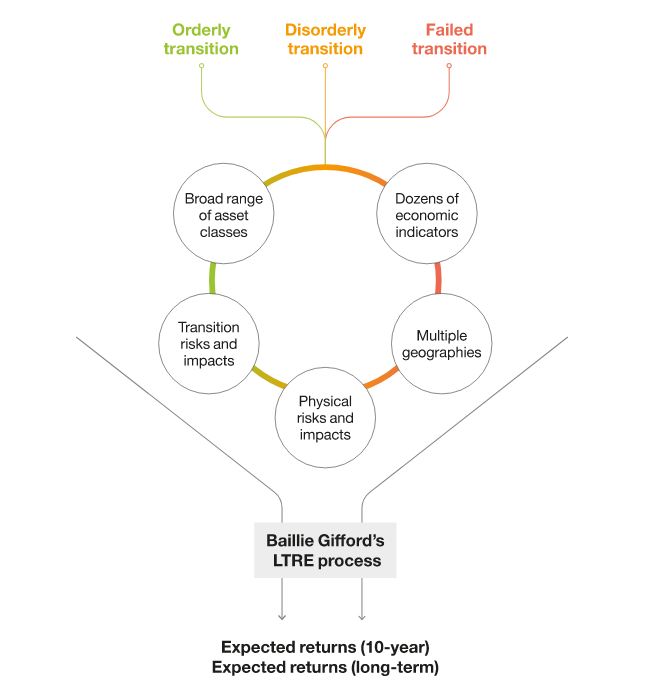

The LTRE exercise is a key part of our Multi Asset investment process. With a broad range of asset classes in which we can invest, understanding the fundamentals of each is important in assessing which will deliver good future returns, and which will not. These long-term views provide context for our investment discussions and over the long run tend to be reflected in our portfolio allocations. Integrating climate scenario analysis more directly into our LTRE exercise is a natural evolution of this process.

Being naturally optimistic, these base case forecasts implicitly assume that the world will broadly achieve an Orderly Transition to alignment with the Paris Agreement goal. The goal is to limit the global temperature increase in this century to 2°C above preindustrial levels, while pursuing the means to limit the increase to 1.5°C. We expect global governments’ climate commitments to continue to develop in the coming years (for example, at the UN Climate Change Conference, also known as COP26, in Glasgow, November 2021) and we expect technological progress over the coming decades to support – and reduce the costs of – that transition. We therefore align our existing forecasts with the Orderly Transition scenario described above and will seek to investigate what the impact on these forecasts would be if our optimism turns out to be wrong. This is an exercise we will revisit periodically, updating both our market assumptions and the various pathway impacts, to review changes over time.

Key Inputs, Assumptions and Outputs

The following diagram sets out the parameters of our analysis and integration of global warming pathways, policy and technological changes, time horizons, geographies, asset classes and climate-informed macro-economic indicators into our proprietary multi asset LTRE investment process, and the associated analysis outputs in the form of adjusted expected asset class returns.

Global warming pathways, narratives and climate-informed macro-economic indicators provided by Ortec Finance. Climate-informed indicators adjusted and input into the LTRE analysis by Baillie Gifford.

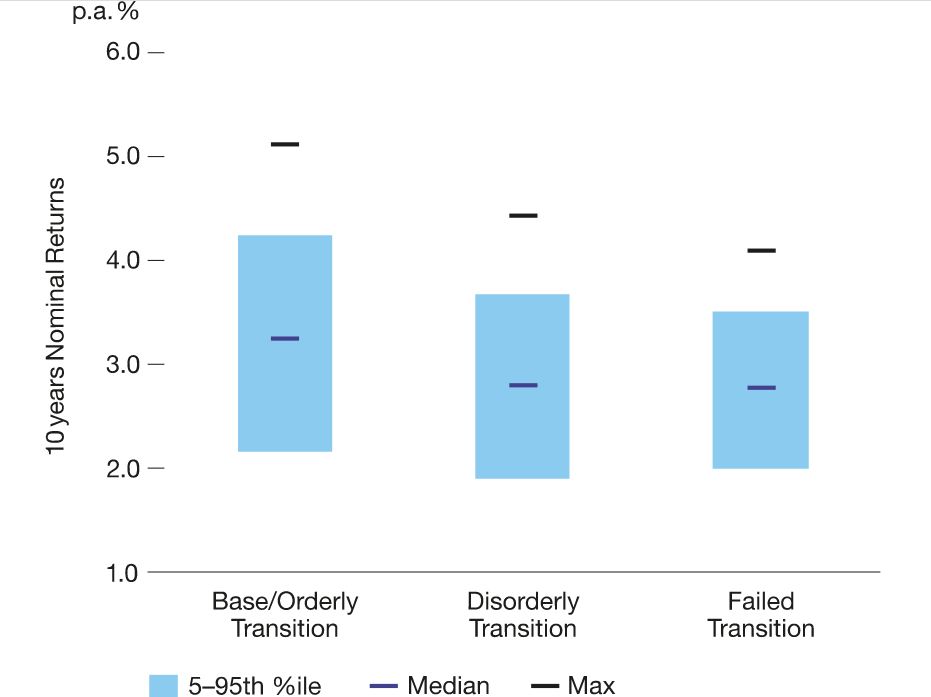

Asset Class Resilience

The next step was to estimate the likely net impacts on asset returns of climate-related events, policy developments and technological changes experienced over the next 10 years and beyond. As noted earlier, we have aligned our baseline expectations with the Orderly Transition scenario, and therefore what we are investigating is the asset class return sensitivities of this turning out not to be the case. In particular, what would we expect to happen if the transition is delayed, and needs an event to kick-start the policy or technological change, ie the Disorderly Transition scenario? And what would be expected if there were no real developments in climate commitments and technological progress, ie the Failed Transition scenario?

The following table shows the adjusted expected returns for the core asset classes under each climate pathway.

Long term return expectations1 – climate-informed scenarios2

All returns are shown here at a global asset class and geographic level, net of any access costs, and so, importantly, assuming that investment is on a passive basis, these should be regarded as minimum achievable returns. We view these estimates as broadly sensible indications of returns and as central projections from a wide range of possible outcomes. They should not be interpreted as high precision forecasts and, even if they prove accurate in the long term, it is very likely that actual returns in the short- to medium-term, and over the course of any given year, will be quite different.

These top-level asset class forecasts mask the underlying detail that, within each area, there will inevitably be winners and losers. Within equity markets, for example, there are outstanding opportunities for companies able to participate, and even lead, the climate transition in the coming years. These tend to be the smaller, more disruptive entities, currently outweighed in equity indices by many less well-prepared companies. This is exactly why we believe an active, forward-looking and optimistic investment approach will be able to generate results in excess of those passive returns noted above.

1. We show the asset class returns to the nearest 0.25 per cent. However, here we show the real GDP growth rates, inflation rates and policy rates on an unrounded basis, to illustrate the differences inherent.

2. Although the differences appear moderate in many cases, bear in mind that these are annualised figures, and the impact of compounding is significant over the investigated periods of investment. Over a decade, the difference between a return of four per cent per annum and five per cent per annum on a £100m investment is almost £15m.

Investment Response

Multi Asset Opportunity Set – 10 years

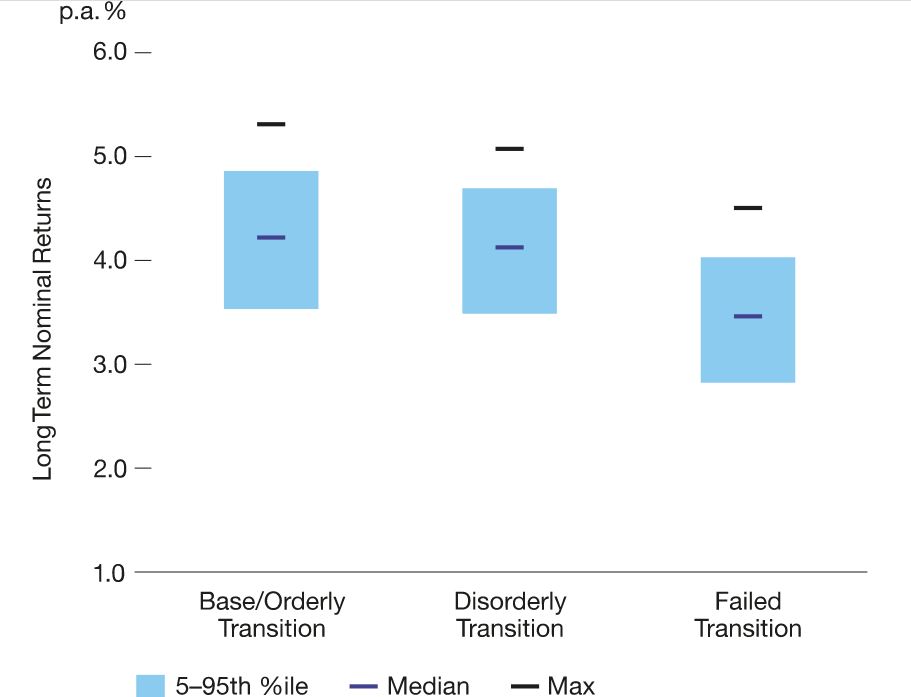

Multi Asset Opportunity Set – Long Term

We see far bigger distinctions in the longer-term numbers beyond the next decade, in the second chart above. Here, the impact of a Failed Transition is clearly visible and fairly easy to imagine; with significantly impaired return expectations for many of the ‘risky’ asset classes, the multi asset investor of the mid-21st century will almost certainly see substantially lower returns if the world follows this pathway.

Putting these together, the situation is clear. The cost of not meeting the Paris Agreement goal may not be fully felt by investors over the same timeframe, but it will have a dramatic impact thereafter. The next few years are crucial.

Looking at it a different way, achieving the Paris targets allows the investment opportunity set to stay reasonably attractive for the long term, and this can be done with limited impact to contemporaneous investment results. In purely investment terms, the mitigation costs need not be high, but the financial, environmental, and social benefits are enormous.

3. Each of the 13,987 unique hypothetical multi asset portfolios contains at least five asset classes and is subject to maximum allocations in each (max 10 per cent in insurance linked securities or commodities, max 20 per cent in cash, investment grade or high yield, max 30 per cent in developed market government debt, emerging market government debt, infrastructure or property, and max 40 per cent in equities).