Investing overseas means investing in a foreign currency too. That can make life a little more complicated, particularly for bond investors.

Post-pandemic divergence in central bank monetary policies has triggered sharp fluctuations in financial markets.

In what former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King describes as the age of “radical uncertainty”,1 such volatility has presented challenges for investors, especially those who invest overseas.

Allocation to overseas assets opens up a world of investment opportunities that are unavailable at home. It also makes a portfolio more resilient by diversifying risks. But it comes with additional complications.

This is because on top of the underlying asset, investors also buy into the currency in which an international security is denominated.

And currencies are tricky beasts – because they can be volatile and unpredictable. They have the potential to influence portfolio returns, sometimes positively, sometimes negatively.

The impact of currency swings is felt most keenly among investors with international bond portfolios. Since fixed income securities return less, often far less, than stocks over the course of a market cycle, a 5 per cent fall in the US dollar, say, would have a bigger effect on euro zone-based international bondholders than on equity investors.

But currency moves this year have been of the sort that happen once in a generation. The yen, for example, lost a fifth of its value against the dollar to hit a 32-year low, while sterling slumped to a 37-year trough against the greenback. The euro fared better in comparison, but still fell to its weakest in 20 years against the US currency.

This means for US-based investors, any gains in the underlying fixed income assets would have been easily wiped out by foreign exchange moves if they did not hedge their currency risks.

This year may be exceptional. Still, experience shows that the world’s major currencies, such as the euro, move up or down by approximately 10 per cent per year, which makes them twice as volatile on average as US government bonds. but half as volatile as equities.2

This is why fixed income investors in particular may want to consider hedging their currency risk.

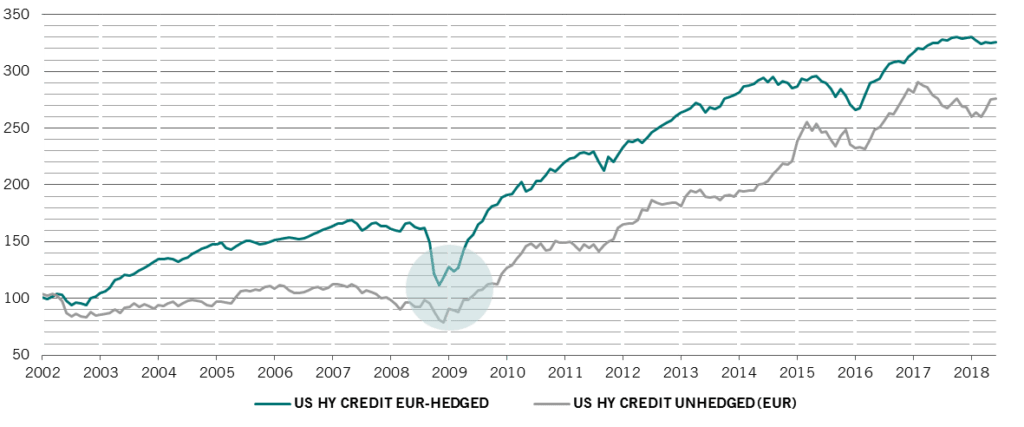

Take the example of a euro zone-based investor holding a portfolio of US high yield bonds. Over a long-term horizon, the investor would have secured a higher and more stable return had they used a currency-hedged investment vehicle rather than a portfolio that did not offer protection from exchange rate movements.

Fig. 1 hedging bets

Performance of US high yield, based in EUR, hedged vs unhedged, indexed

But currency-hedged bond investments – which use instruments known as forward exchange forward contracts (a more detailed explanation is below) – don’t always deliver better returns. And performance doesn’t always depend on an investor’s time horizon.

A currency can, in fact, appreciate or depreciate for an extended period of time – months, or even years – sometimes moving way beyond what economists consider to be a fair level.

This means that investors who opt to insure themselves against adverse moves in exchange rates also forego the opportunity of securing positive returns from currency trends that go in their favour.

The events of 2008 and 2009 highlight why currency hedging can be counterproductive in fixed income. Then, US high yield bonds were falling sharply as investors were worried about a wave of company defaults (Fig.1, shaded area).

At the same time, however, the US dollar was gaining in value because of the currency’s defensive attributes. This meant that euro-based investors who had opted to insulate themselves from moves in the USD/EUR exchange rate experienced a significantly bigger drop in their investments compared with their non-hedged counterparts, whose portfolios were cushioned by the appreciating greenback.

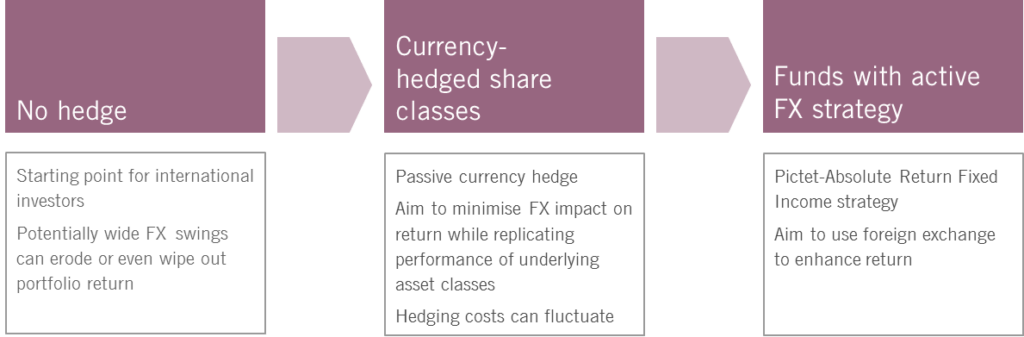

Currency hedging choices

There are various ways for investors to manage their currency exposure (See Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Currency hedging at a glance

A popular option is to outsource the task of currency hedging to a third party, typically the fund administrator, via currency-hedged share classes.

Currency-hedged share classes aim to minimise the impact of currency swings on the portfolio return.

Investors get peace of mind, in exchange for a fee that works much like a premium on an insurance policy.

Such vehicles allow investors to gain access to types of investment that aren’t traditionally available in certain currencies – such as emerging market debt in euros or US high yield bonds in the Swiss franc.

Investors who have a strong conviction in the future trajectory of their base currency can easily switch from one share class to another, while staying fully invested in the underlying asset class.

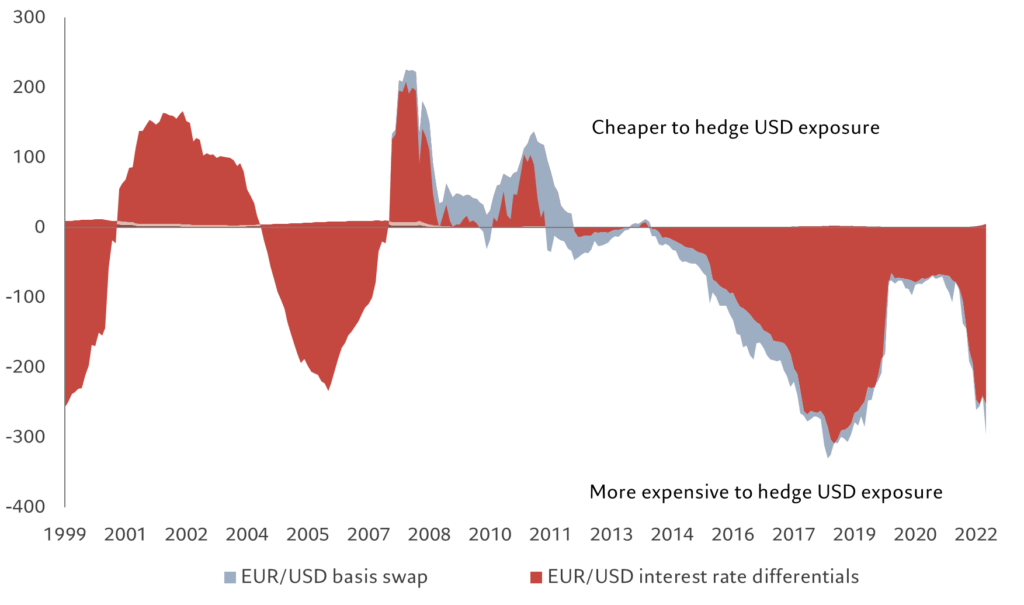

It is important to remember, however, that currency-hedged share classes cannot completely eliminate the risks associated with movements in exchange rates. The cost of currency hedging for can fluctuate too (see Fig. 3), which also has an impact on portfolio returns. The cost of a currency hedged investment vehicle has three components to it.

- Interest rates: a currency hedge uses instruments known as foreign exchange forwards. These are contracts in which two parties are obliged to exchange a pre-determined fixed amount of (foreign) currency for another (base) currency at a specified future date. The cost of these contracts – or the future exchange rate at which the transaction takes place – is primarily determined by the difference in the interest rate of the base currency and the foreign currency. This pricing mechanism dictates that the currency with the lowest interest rate will change hands at higher exchange rate in the future. So, if interest rates in the US and euro zone were exactly the same, the hedging cost would be close to zero and a EUR-hedged share class of a portfolio of US bonds would return the same as its USD counterpart. But if US interest rates were to rise and those in the euro zone were to fall, the currency hedging cost would rise for EUR-based investor.

- Admin fee: investors are required to pay the cost of managing a hedged share class, typically 5 basis points per year. This is usually incorporated into the fund administration fee.

- Transaction costs: market spreads, known as euro/dollar basis swap, mean there is a cost to enter into spot, forward or swap contracts. The more illiquid a currency pair, the higher the cost. Transaction costs typically rise towards the year end due to thin liquidity.

Example of an active approach

Many global bond portfolios treat currencies as distinct sources of return and risk. They deploy what are known as currency overlay strategies to benefit from both long and short-term trends in the foreign exchange market as well as swings in currency hedging costs.

Pictet Asset Management runs a number of fixed income strategies that actively manage currency exposure in this way. Broadly speaking, our aim is to identify and invest in unjustifiably cheap currencies to enhance portfolio returns.

For example, our emerging fixed income strategies took underweight positions in central European currencies in the third quarter of 2022 as they came under most pressure from high inflation and the European gas supply issues. At the same time, they were overweight in selected Latin American and Asian currencies. These positions contributed positively to the portfolio’s return.

In more recent months, they have started to unwind these positions to take a more neutral view on emerging currencies as the Federal Reserve appeared closer to the end of its tightening campaign, while keeping some underweight positions in selected central European currencies.

Investment managers of the Pictet-Emerging Local Currency Debt strategy, meanwhile, made investments in the Argentine peso in the latter part of 2018 in the belief the currency was due a sustained rebound after its recent sharp fall. The currency investment contributed positively to the portfolio’s return as the peso gained nearly 10 per cent against the dollar in the final three months of 2018.

Currency hedging: blessing and curse

What’s less well understood about the foreign exchange market is that the mechanics behind the calculation of currency forwards can, at times, render certain bond markets completely out of bounds for foreign investors.

That’s currently the case for euro-based investors looking to invest in US government bonds. Because US interest rates have been rising faster than those in the euro zone, the cost of hedging a 10-year US government bond, currently yielding some 3.70 per cent, into euro has risen to prohibitively expensive levels (see Fig. 3). Using a EUR/USD currency hedge in this instance would take the effective yield of the note to levels below zero. By comparison, the 10-year German government bond yields around 1.7 per cent. While this quirk is problematic for euro-based investors, it is a represents a potentially rich source of return for dollar-based investors, who effectively receive a premium when the hedge any euro-denominated bond investments back into the dollar.

Exchange rate fluctuations, then, can greatly impact the return from fixed income portfolios. If you thought currencies were a zero sum game, think again.

Fig. 3 cost breakdown

Average cost of currency hedging in EUR/USD (in basis points, annualised)

[2] Based on weekly historical volatility of JP Morgan US Treasury Index spot EURUSD and S and P 500 index.

Source: Bloomberg Pictet Asset Management data covering period 25.01.2009 to 25.01.2019