In an increasingly multi-polar world, the prominence of the RMB is rising slowly but surely. This bodes well for the long-term demand for RMB-denominated bonds and is likely to have a positive spillover effect for other local currency Asian bonds.

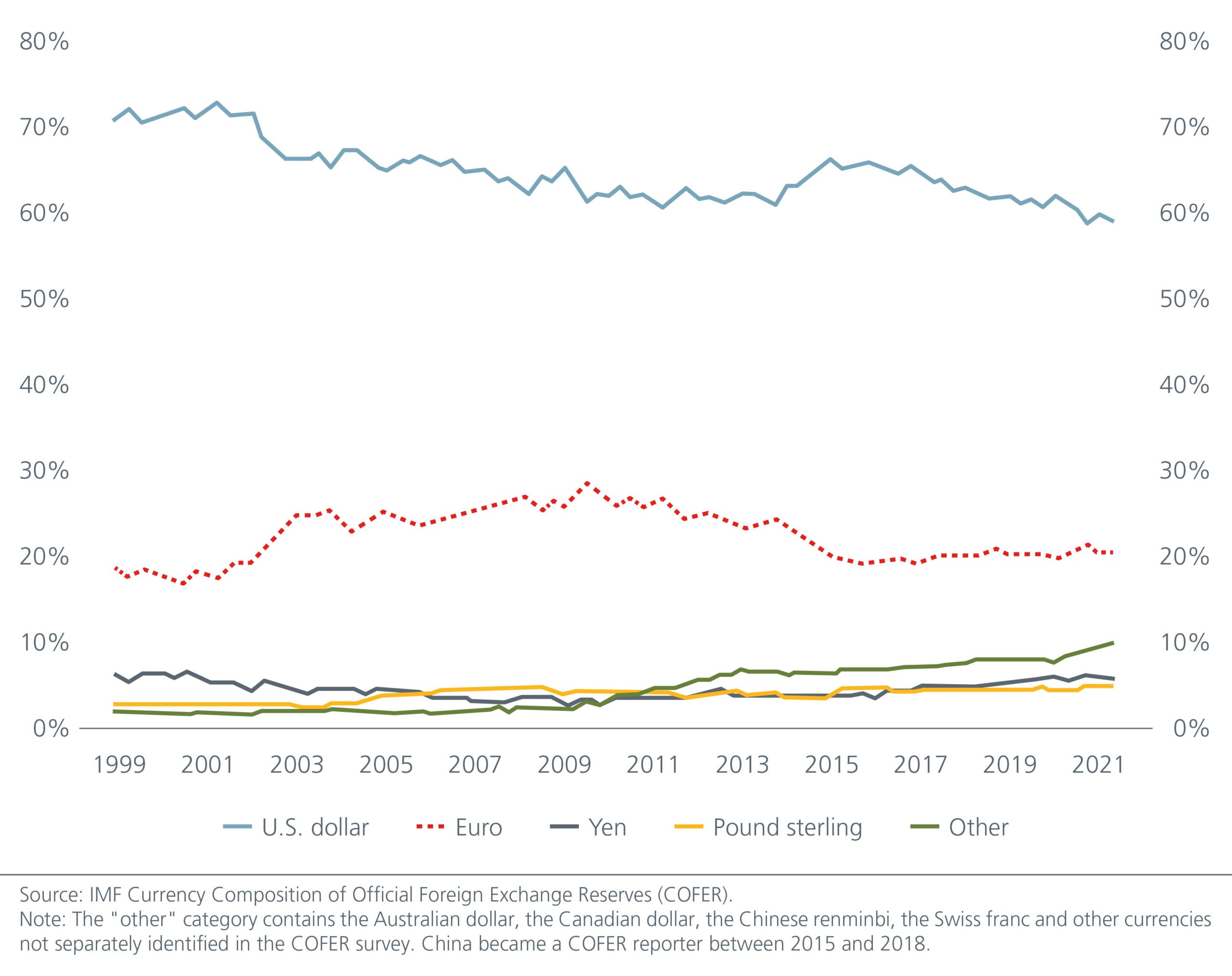

The USD is the world’s most dominant reserve currency post World War II and Bretton Woods. Despite the US economy making up less than 20% of global GDP in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms, close to 90% of global currency transactions involve the USD and nearly 40% of global debt is issued in USD. As of 2021, the USD accounted for close to 60% of global central banks’ foreign exchange reserves. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Currency composition of global foreign exchange reserves

Questions over the USD’s dominance as a reserve currency are not new. Over the years, critics have highlighted the US’ exorbitant privilege to be able to fund massive private and public borrowing at attractive interest rates, as well as its extraordinary influence over global financial systems. Yet till now, few currencies have been able to displace the USD’s reign, although the winds of change may be emerging more strongly.

What it takes to be a reserve currency

Reserve currencies are chosen based on economic and security considerations. Safety, liquidity, network effects, trade links and financial connections explain why some currencies are used disproportionally as a medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account by governments and private entities engaged extensively in cross-border transactions.

In this regard, a currency underpinned by a large, strong, open economy, accompanied by deep liquid capital markets – lending economic influence and macroeconomic stability – would serve the above considerations well.

Beyond pecuniary considerations, academic research (Eichengreem) has shown that the composition of international reserves also depended significantly on geopolitical, strategic, diplomatic and military factors. Countries see it in their geopolitical interest to conduct majority of their international transactions using the currency of their allies or a very strong partner.

In the past four decades, the USD has fulfilled the criteria of liquidity and safety without equal. The relative strength and importance of the US economy support the value of the dollar. Investors and reserve managers favour USD-denominated assets from a risk-reward perspective by virtue of its safe-haven status and the economy’s robust – albeit deteriorating – fundamentals.

US capital markets are the largest in the world, making up 41% of global equity and 40% of global fixed income markets, thus providing reserve managers highly flexible and liquid options in deploying their foreign reserves.

An unprecedented period of trade globalisation from the 1990s, where the value of exports as a share of GDP rose from 15% to 25% today, also benefitted the USD, as majority of goods were traded in dollars.

Meanwhile, Germany, Japan, and Saudi Arabia – allies of the United States – also choose to hold the bulk of their foreign reserves in USD.

The USD may no longer be “safe”

The US and its allies announced their intention to freeze the Central Bank of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. To date, about half of Russia’s USD643 bn in reserves is frozen by the US and its allies while only its reserves held in RMB and gold remain accessible.

The willingness of the US to weaponise the USD has caused led reserve managers to re-assess the “safety” of their reserve assets. This is especially so for countries which are not traditional allies of the US or which do not embrace the US’ and its allies’ brand of political ideology. The dilemma faced by such regimes was laid bare in 2019 when then US President Trump, in response to China’s treatment of protestors in Hong Kong, threatened to impose financial sanctions on China including denying Chinese financial institutions access to USD funding markets.

De-globalisation and the emergence of regional trading blocs

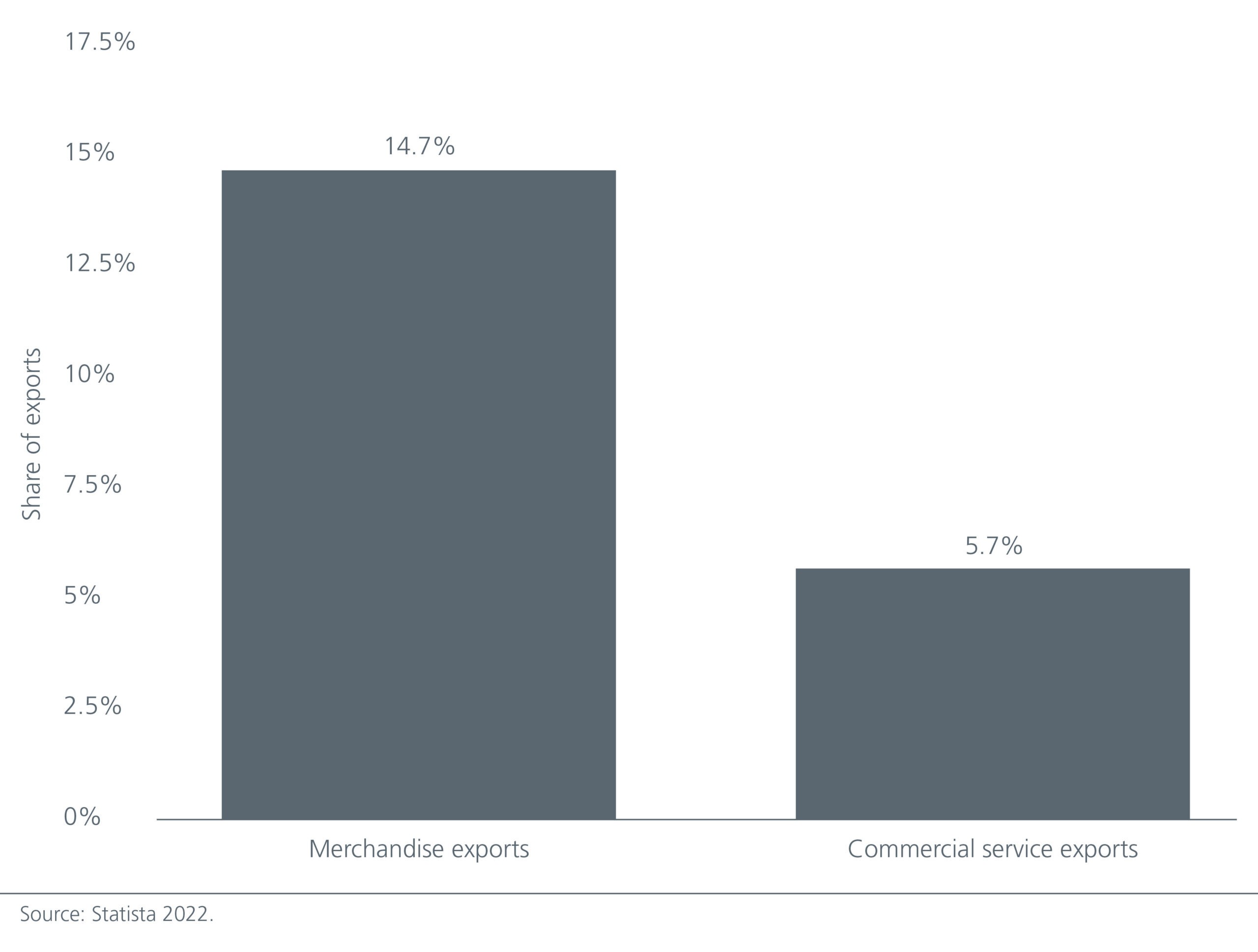

If globalisation defined the global economy in the 1990s and early 2000s, then the 2010s marked the peak and reversal of such a megatrend with the US-China trade war in 2017. Yet while global trade volumes and value peaked in the 2010s, China’s share of global exports continues to grow and currently stands at 15%, providing it significant financial and economic clout. See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. China’s share of global exports in 2020

The imposition of tariffs and push for localisation of manufacturing have spurred the development of regional trade blocs that feature China prominently.

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a transpacific economic partnership amongst countries across Asia, Europe and Americas (with the exception of the US) came into force in 2018. In 2020, China signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership with 14 other Asian countries, mostly from the ASEAN bloc. That year, the ASEAN group of countries became China’s biggest trading partner, replacing the European Union.

Meanwhile, the African Continental Free Trade Area which aims to accelerate intra-African trade and connects 55 African economies, has been ratified by 38 countries. A regional trading bloc of 1.3 billion people with a total income worth USD3.4 trillion may be a boon for China as it has been the largest investor in Africa over the last ten years.

The dominance of the USD may be increasingly threatened by the emergence of these Sino-centric economic trade blocs.

RMB – the emergent alternative reserve currency

For reserve managers who may not embrace the US’ political ideology, the emergence of the RMB as a credible alternative reserve currency provides a potential source of diversification. China has been incrementally opening up its domestic capital markets to foreign institutional investors since the 2000s.

China’s alternative payments system, the RMB Cross-border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), which offers clearing and settlement services for participants in cross-border RMB payments and trade, was launched in 2015 to increase the global use of the RMB. It has recently been explored as an alternative system to SWIFT amid sanctions levied by the US and Europe on Russia.

In 2016, the RMB was added to IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR), augmenting its status as a reserve currency alongside the USD, EUR, JPY and GBP. The internationalisation of the RMB continues to gain pace, with the recent introduction of the digital yuan intended to facilitate the RMB’s international circulation and usage.

China also introduced RMB-denominated oil futures to the Shanghai International Energy Exchange (INE) in 2018. Since then, activity in this market has risen to record levels, with trading volumes climbing more than 20% each year. The specter of sanctions to be imposed on Russian oil exports – and possibly extended to oil trading and hedging in established commodity exchanges – could accelerate the shift of transaction activity into RMB and Chinese exchanges.

The RMB currently makes up just 3% of global currency reserves, but its weight is likely to grow given the size and importance of China within the global economy. In PPP terms, China’s GDP had surpassed the US’ in 2014 and the Chinese economy continues to grow significantly faster than the US and Europe.

A boost for RMB-denominated assets and Asian fixed income

The USD has enjoyed a period of unrivalled dominance over the past four decades, but its current share of global reserves appears questionable in an increasingly multi-polar world. In a recent paper, the IMF noted that the USD’s share in global currency reserves has been steadily declining since the turn of the century. A quarter of the shift went into the RMB and the rest was into currencies of smaller countries that have traditionally played a more limited role as reserve currencies, such as the AUD, CAD, KRW and SGD. Growing liquidity as well as more active reserve management have benefited non-traditional reserve currencies with attractive risk-adjusted returns1.

Research suggests that the RMB’s share of global foreign exchange reserves can rise to 10% by 2030 amid incremental reserve diversification in sympathy with China’s growing economic and financial clout2. Renowned international economist Kenneth Rogoff has also indicated that the RMB’s share in global reserves can increase to be comparable to that of the USD if the RMB becomes more flexible and easily convertible.

As China projects greater economic and political influence over its regional and trading partners in the coming years, the centre of gravity in reserve management should eventually shift towards China, and by extension, Asia, which as a region would gradually and inexorably increase its share of global economic output. While this transition will not happen immediately, the gears are already set in motion, and likely to accelerate as geopolitical tensions rise. We believe that these developments bode well for the demand of RMB-denominated bonds, as well as other local currency Asian bonds over the long term.