The impact of the rise and fall in state policy and regulatory actions on Chinese innovation and private sector confidence

Chinese entrepreneurs have been doing business under a rapidly changing macro and regulatory environment in the past few years. The government’s recent pivot to prioritizing growth and pulling back regulations in some areas was a welcome move, but a clear overall positive effect has yet to materialize. Has the Chinese entrepreneurial spirit been stifled?

Not an easy time

A quick look at the headline numbers suggests Chinese companies are struggling: The private sector has been shrinking in the past three years. According to Peterson Institute for International Economics, private enterprises made up about 36% of the country’s 100 largest listed companies at the end of 2023, a steady and marked drop from the 55% peak reached mid-2021.1

A deteriorating business environment could be a factor. Out of about 50 comparable economies covered by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, China’s entrepreneurial environment ranked tenth last year, having fallen considerably from fourth in 2019.2 Chinese entrepreneurs participating in the survey cited financing as their biggest pain point, specifically challenges in coping with taxes and bureaucracy as well as a lack of government support. The survey results also showed individual’s lowest intention among the tracked economies to start business in the next three years.

Sentiment is down but holding

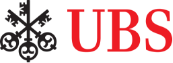

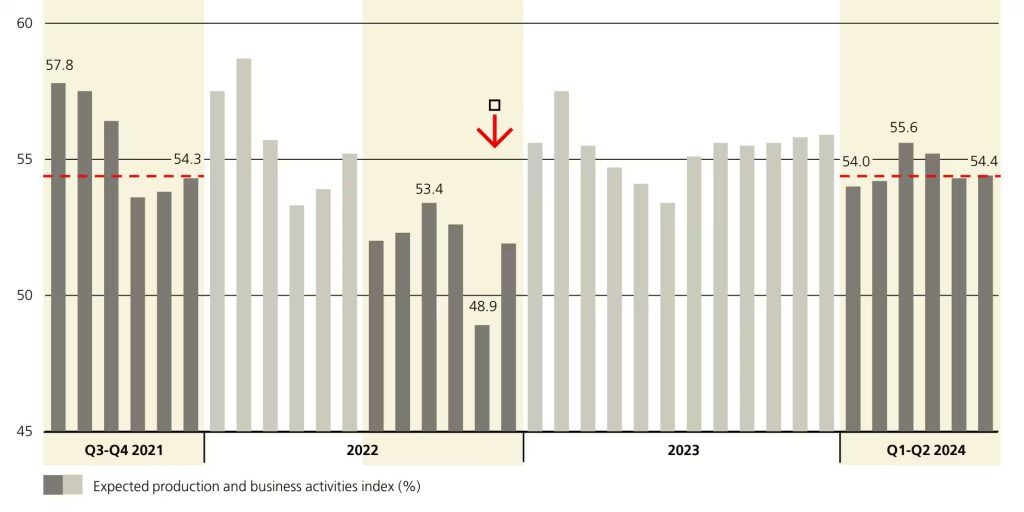

Official data, however, tell a somewhat different story. Expected production and business activities numbers from the manufacturing and non-manufacturing purchasing managers index (PMI) series are down from three years ago, but not by a large margin (see charts below).3 Business expectations at the end of the first half of the year are significantly below the exuberant level immediately following the country’s reopening, yet they are much higher than the record low from the COVID lockdown days. Expectations are nowhere near depressed levels. In our opinion, the disparity should prompt investors to do a double take.

Chart 1: Expectations from Chinese manufacturers are holding

Manufacturing PMI

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China, as of 30 June 2024.

This chart shows business expectations from Chinese manufacturers from 2021 to 2024.

Chart 2: A similar picture from Chinese non-manufacturers

Non-manufacturing PMI

This chart shows business expectations from Chinese non-manufacturers from 2021 to 2024.

More connected now

Today the private sector plays a significant role in China following several decades of reforms to reduce the direct role of the state in the economy. Although legislations allowing and formalizing the establishment of the modern day corporate enterprises first occurred in 1988, private companies have flourished since and now account for more than 60% of GDP and 80% of urban employment.3

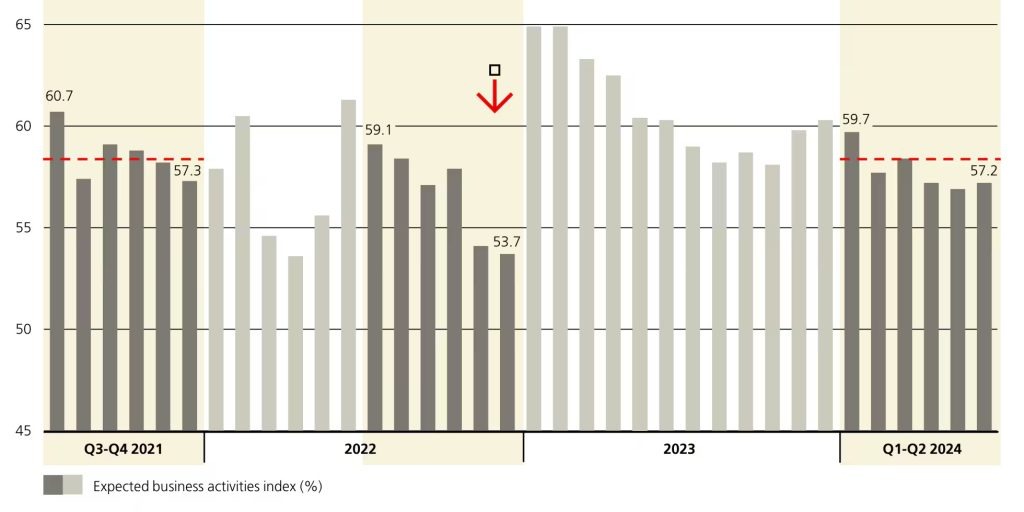

When the regulators tightened controls over sectors including property, education and technology a few years ago, it was billed as a public and private sector clash, with the state turning against private companies. Given many private companies have strong equity ties to the state, this is somewhat of an oversimplification.

As of 2019, 78% of the 1,000 largest private companies were either directly or indirectly connected to the state (see chart below).4 The number of state-connected entrepreneurs jumped significantly between 2000 and 2019, blurring the line between public and private.

Chart 3: Strong links between public and private

State connections among top 1,000 private owners

This chart shows the percentage of state-connected entrepreneurs among the largest private companies in 2020.

A large share of China’s economy is therefore neither wholly state owned nor fully privately owned. History provides context. Mixed ownership – companies that are structured as public-private enterprises – existed in imperial China when large family businesses operated with state sponsorship, as well as at the turn of the 20th century with the first adoption of a capitalistic model with Chinese corporate governance characteristics.

Animal spirit

That said, Chinese entrepreneurs are making the country’s priorities their own and have proven to be resilient and resourceful when faced with the changing trajectory of state policy. Not only are they experienced in doing business under considerable government rules and oversight, most operate in an uber-competitive environment. The ferocity of domestic competition makes them quick to adapt to an uncertain environment with new strategies. Many are looking abroad for new growth opportunities, competing in international markets with success. Regulatory checks and balances are unlikely to stop these survivors.

We were reassured of that fact on our recent research trip to the Yangtze River Delta by – of all things – the ready-to-drink tea market. Tingyi and UPC (Uni-President China) in the second quarter hiked prices of their bottled tea, popular among blue collar workers, because of stronger purchasing power on the back of income growth that is slightly outpacing office workers.

Broadly speaking, business sentiment in the delta is meaningfully more constructive than Tier 1 cities like Beijing and Shanghai. It is at least partly owing to a strong pickup in manufacturing activities, as entrepreneurs in a wide variety of subsectors are finding success in a slower growth environment. From shipbuilders to excavators, from injection molding machine makers to industrial elevator builders, entrepreneurs are thriving amid intense competition from the midstream manufacturing space.

A rising manufacturing cycle is translating into healthy labor demand and better pay for blue collar workers, who can afford more expensive bottled tea. The price hike and its significance, however, were mostly overlooked, even though a price correction for premium liquor Moutai was widely reported as a sign of the economy showing major cracks.

When it comes to China, it helps to do a double take and look for the story behind the headlines. China is a country of nuances and contradictions, and our visit outside of the most prominent cities was a good reminder of Chinese entrepreneurs’ animal spirit – a steadfast determination to succeed.

1 Source: Tianlei Huang and Nicolas Véron (2024). Share of China’s top companies in the private sector continued to steadily decline in 2023. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

2 Source: GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor) (2023). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2023/2024 Global Report: 25 Years and Growing. London: GEM.

3 Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China. July, 2024

4 Source: Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, Zheng Michael Song, and Xin Wang (2020). The Rise of the State-Connected Private Owners in China. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper.