Emerging market debt – both sovereign and corporate – should benefit as the dollar’s relentless advance of the past 15 years starts to run out of steam.

Aligning stars

Additional contributions from Christopher Preece and Patrick Zweifel

The stars are aligning for emerging market (EM) debt. And according to our analysis, there are good reasons to believe these assets – both sovereign and corporate bonds – are on the cusp of an upswing that could last for years to come.

To begin with, there’s a shift in the direction of the US dollar. The signs are that the currency’s relentless advance of the past decade is starting to run out of steam. US exceptionalism is being called into question: investors’ appetite for risk is steadily returning following the Covid pandemic, the initial shock caused by the Ukraine war and years of disinflation and distortive monetary policy.

And with the dollar playing a smaller role, other factors are likely to take over in driving EM fixed income.

One boost is likely to come from China’s dramatic volte-face on its Covid policy, dropping draconian lockdowns for complete reopening of its economy.

Then there’s EM economies’ deft handling of inflation. EM central banks acted early and decisively to contain inflationary pressures, leaving developing economies well placed to significantly outgrow their developed counterparts.

Together, these factors are bound up in what is arguably the most important source of EM fixed income performance: foreign exchange.

For EM fixed income, currency movements are consequential – not only for bonds issued in local currencies but also for those denominated in US dollars. Currency movements can create feedback effects that have a major bearing on a country’s overall finances. Similarly, they can have a critical role to play in EM corporate balance sheets.

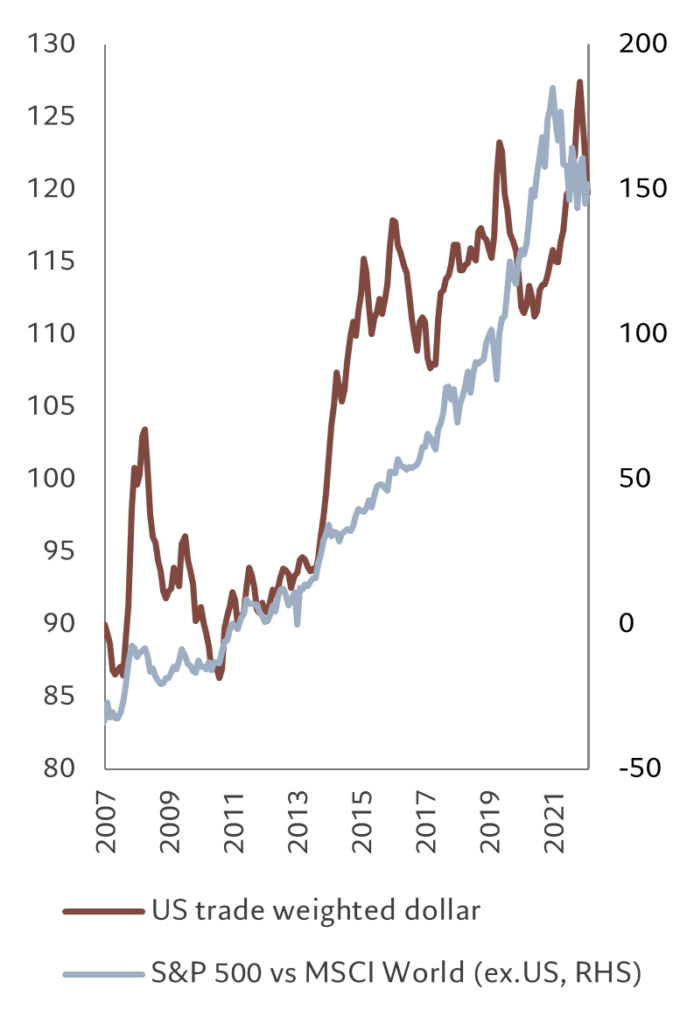

For investors, this can result in substantial compounding effects – appreciating local currencies generate virtuous cycles that feed through to fixed income returns. This is apparent in the relationship between the dollar’s relative value and how global asset markets perform – a weaker dollar tend to be associated with relative strength in non-US assets and a strong dollar with stronger US assets (see Fig. 1).

The dollar might not be mighty much longer

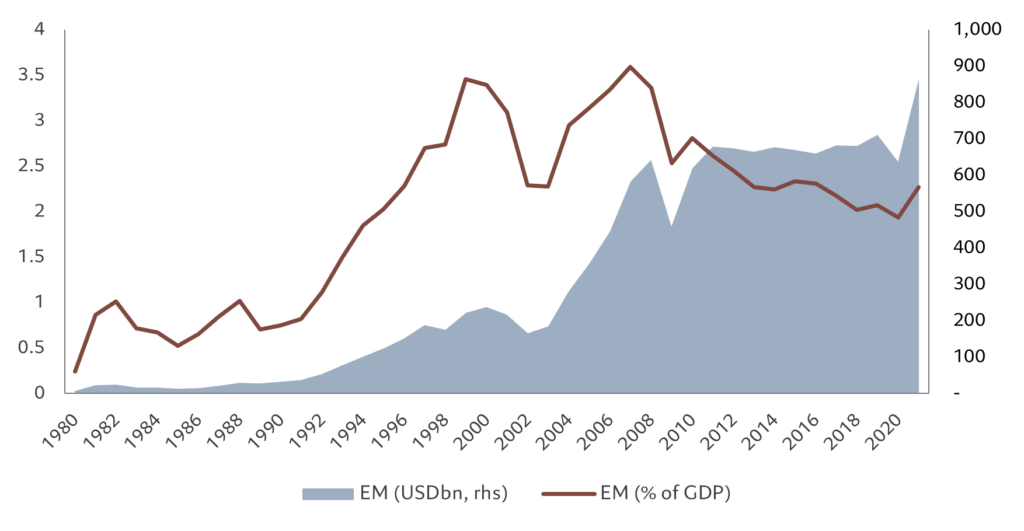

Since the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009, the dollar has been on a relentless march higher, particularly against emerging market currencies. Between June 2008 and November of 2022, it appreciated nearly 50 per cent on a trade-weighted basis against an EM basket. That advance left the greenback more than 10 per cent overvalued and EM currencies undervalued by more than 20 per cent (See Fig. 2).

The dollar’s strength was more or less universal – it moved higher against nearly all currencies, whether in developed or emerging markets. A turn in the dollar, or even a flattening should be supportive for EM assets.

Market watchers are rightly wary of simple valuation arguments for currencies. Yes, there is ultimately likely to be reversion to fair value. But it can take a very long time to unfold, often sparked by unanticipated events. Nonetheless, we think there are good reasons to believe the dollar has started a secular decline.

First, it’s worth considering why the dollar has been so strong for so long. One reason is US exceptionalism. Much as the greenback is the world’s reserve currency, US monetary policy sets the pace for other central banks.

At the same time, the country’s asset markets dominate global capital, with outperformance of US equities driving flows which in turn reinforced demand for the dollar. This outperformance has fuelled significant valuation premia for US assets, particularly in the interest rates sensitive tech sector, whose valuations saw outsized benefits from the now defunct low rate regime. A shift towards private assets was also a contributing factor to these capital flows given that US private markets are so much more developed than they are elsewhere. And American innovation, the size of its economy, its access to capital all merely increase the dollar’s gravitational pull (see Fig. 1).

Then there’s the matter of risk aversion. The global financial crisis sent investors everywhere scurrying into the safety of liquid US instruments. That was compounded by Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014, the Covid pandemic in 2020 and then again with the second Russian invasion last year.

Together, these crises have given the dollar a relentless momentum, which, in turn, has resulted in its significant overvaluation relative to its structural fundamentals.

But now, a massive twin deficit – 7.2 per cent of GDP – a heavy domestic debt load that puts pressure on the US Federal Reserve to inflate away part of the burden and waning foreign demand for US assets are all calling into question how long the currency can levitate.

EM bears the burden

Years of strong dollar dynamics have had a far reaching consequences for emerging economies, much of it played out in the currency markets.

With global investors focused on US assets, foreign direct investment into developing countries has waned (see Fig. 3).

At the same time a rising dollar has increased debt servicing costs and interest burdens on EM governments and corporates borrowing in the US currency.

As if that wasn’t enough, a strong dollar also contributes to inflation pressures in EM – with imports priced in dollars feeding into higher consumer prices. This forces central banks to tighten policy to limit currency depreciation, either by way of interest rate hikes or interventions in currency markets, which drains foreign exchange reserves. Not only does this add to the cost of servicing domestic debt, it also erodes sovereign buffers.

Over the years, EM currencies declined in value as their central banks struggled to balance the need for higher rates and to maintain growth. EM growth differentials over the US weren’t generally sufficient to attract investors. But at the same time, EM risk premia weren’t sufficient to buffer against these countries’ idiosyncratic risks. The dollar was made even more attractive to international investors by the fact that non-US developed markets were keeping interest rates artificially low, driving a significant portion of their bond markets into negative yields.

Corporates endure

EM corporations with foreign currency debt found life particularly tough during the decade-plus of dollar strength. Weak currencies put pressure on profits among companies with a domestic focus but with hard currency liabilities. High domestic interest rates make for high costs of funding. And at the same time, currency volatility makes balancing cash flows complicated, as companies have to negotiate spending on large capital investments that are often priced in dollars against income flows in domestic currencies – hedging costs can be considerable.

And that’s without factoring in one of the biggest considerations: politics. Central banks starved of hard currency will often tap up the country’s biggest corporations, in effect levelling capital controls.

EM banks can find life tricky too – domestic savers keen to protect themselves against inflation will seek out hard currency savings accounts. The banks offering these accounts then have the difficulty of finding where to house the cash while maintaining liquidity.

Paradoxically, some of the biggest commodity firms are subject to the biggest political penalties. Take EM oil and gas producers. Normally, they’d be insulated from currency effects – prices are in dollars as are many service and capital costs of production and exploration. But fuel prices tend to be strictly controlled in many of these countries for political reasons, often kept well below global benchmarks. Oil shocks and local currency devaluations can therefore be as much of a burden as a benefit to these companies. That’s not to say EM companies have simply sat back and taken the hit. Many have found ways to mitigate the effects of foreign exchange volatility. In some cases, these lessons became insitutionalised – so, for instance, some firms have adopted internal dollar-linked pricing formulas even when revenues are in local currencies.

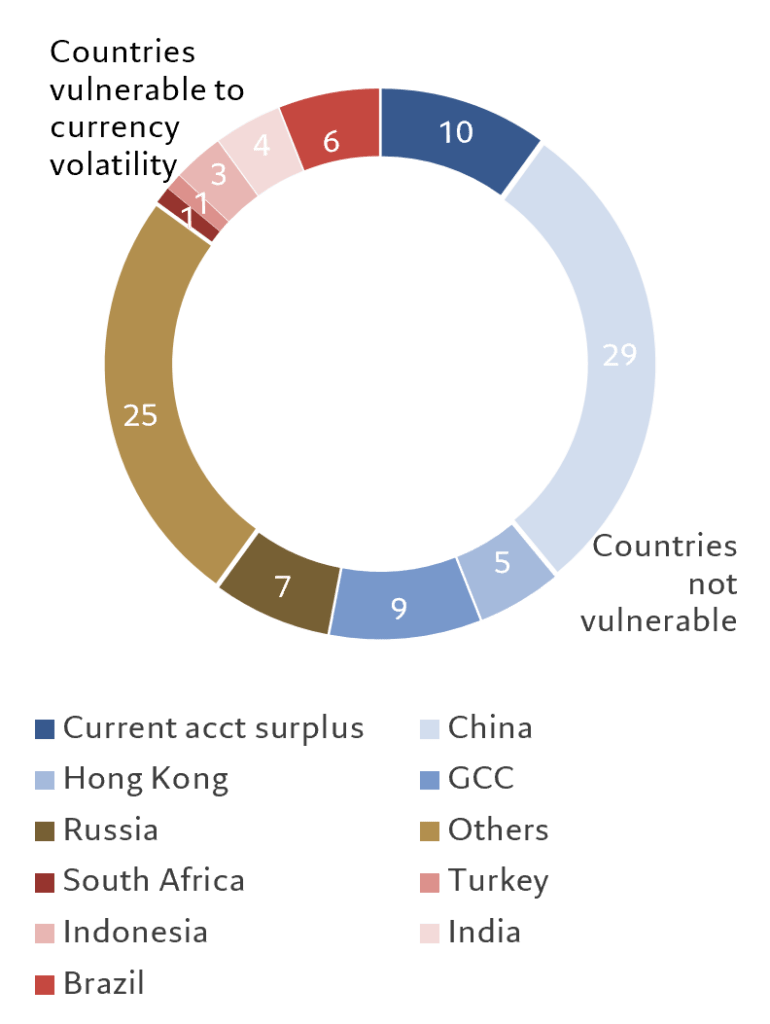

EM corporations have worked hard to insulate themselves from the effects of dollar volatility – and in many cases they’ve been helped by the fact that their home countries have either pegged their currencies to the dollar or have managed floats or have current account surpluses (see Fig. 4). Nonetheless, a weakening dollar will take the pressure off corporates, particularly in the likes of Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa.

The cycle turns

As US exceptionalism becomes less important and the secular dollar cycle starts to turn, EM bonds should come into their own. A rise in the value of their domestic currencies reduces the relative burden of financing that debt and reduces debt ratios – be it in terms of GDP or, in the case of companies, market capitalisation. As their dollar debt burdens become more sustainable, EM sovereign and corporate borrowers benefit from improving credit ratings and, simultaneously, a decline in their cost of capital. Resources that otherwise would have gone to covering debt are released into the wider economy, which boosts growth. Capital also flows from abroad, boosting productive potential. Improving growth differentials gives a further lift to the currency and a virtuous – and often multi-year – cycle becomes embedded.

“Emerging market cycles last a long time. Catch them right and investors can benefit from rewarding upswings for many years. “

This cycle is likely to be reinforced further by an upswing in global capital spending. Much as central banks were the agents of financial repression during the past decade by keeping official interest rates well below their natural rate, developed market governments are poised to do something similar by launching massive and unfunded capital spending programmes. With taxes covering only part of the costs, the remainder is likely to come from inflation. Given that EM countries are a major source of raw materials while they also tend to have less debt and more favourable demographic, they should benefit most from this new cycle of financial repression.

The fact that EM currencies start from a level of extreme undervaluation – two standard deviations below trend, according to our estimates – there is substantial scope for a very long, steady appreciation. At the same time, yields on EM fixed income now comprise an attractive risk premium, which is to say they pay for investors to take EM risk. In part that comes from interest rates and the yield spread EM assets offer over their developed country peers.

Getting there early

Emerging market cycles last a long time. Catch them right and investors can benefit from rewarding upswings for many years. Crucially, one such upswing looks to be starting right now. Those who catch the sea-change early are likely to benefit most. But investors need not throw themselves into the market for fear of missing out, they can dip their toes in slowly and build positions over time.

What they shouldn’t do, however, is forget that there will be reversals along the way or ignore idiosyncratic risks. Dispersion in these markets presents opportunities for active managers to navigate shorter cycles while benefitting from powerful structural trends such as the one we have laid out. It is essential to invest on the basis of a strong analytical process, that facilitates a deep assessment of top-down macro and bottom-up idiosyncratic fundamentals.