Marc Rovers takes a panoramic view of the challenges facing European credit markets – and the opportunities they may hold

When we meet clients, one question comes up more than any other. What returns can we expect going forward?

This is a difficult question at any time, but under current market conditions it’s more difficult to answer than ever.

This difficulty reflects the unprecedented volatility in fixed income assets in recent months.

MOVE-ing on up?

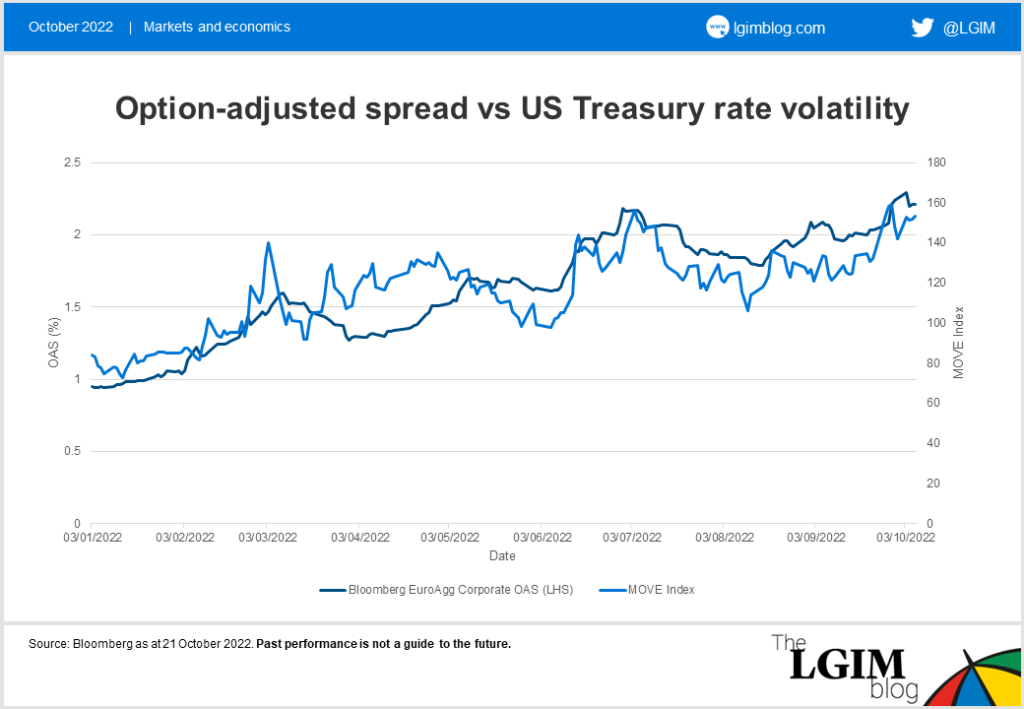

One indicator we watch closely is the so-called MOVE index, which captures the option premium traders charge for hedging rate risk in the US Treasury market.

The graph below shows the MOVE index in relation to the spread of Euro investment grade credit versus German government bonds (the option-adjusted spread or OAS) since the start of the year:

Uncertainty about rates is extremely high at present. This uncertainty is in part a product of both the very high inflation Europe is experiencing and the lack of clarity on its future trajectory.

The best protection against this volatility is to limit our exposure to interest movements. Due to the limited duration of Euro credit – around 4.5 versus durations of about two years longer for the USD and GBP market – its returns have been less negative.

We believe the current yield of over 4.25% will also provide something of a buffer against further rate rises, since due to this positive carry this yield would need to go up by more than 1.25% over a 12-month time period before total returns turn negative.

Spreads go wide

Next to rates, credit spreads and default rates are of key importance – and have also been very volatile.

International capital markets are strongly connected, with both rates and credit spreads in the US and Europe often moving in tandem. However, Europe’s greater vulnerability to the energy crisis due to its exposure to Russian gas supplies disrupted by the war in Ukraine has meant credit spreads in Europe have moved much wider compared to USD.

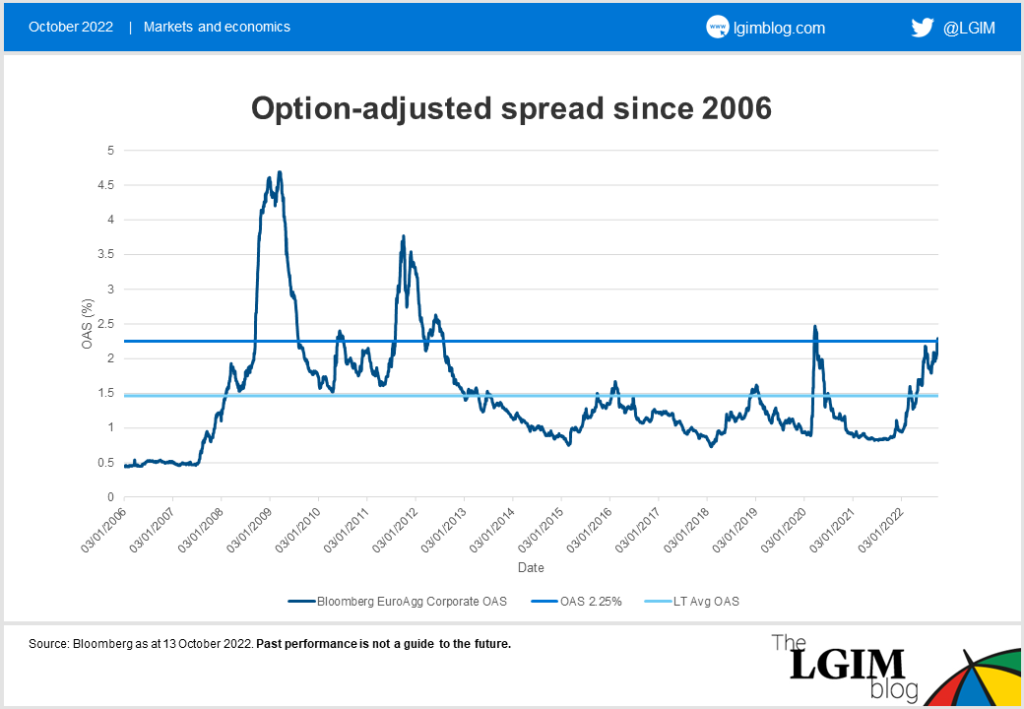

Putting this in a historical context, investment grade Euro credit spreads are at around 225 basis points. These are levels beyond what we’ve seen before, for example at the height of the commodity crisis in 2015/2016, and are akin to the roughly 250 basis points mark we saw at the peak of the Covid crisis. The average OAS of the Bloomberg EuroAgg Corporate index going back to 2006 is 1.46%.

Quantitative analysis going back to 2006 shows that at these levels, over every 36-month period Euro credit generated a positive excess return versus German government bonds: an average of more than 4% in total.

The bear case

History is not necessarily a guide for the future, and therefore we must factor in default risk to our scenario planning.

In a scenario where we face a long and deep recession, many banks and companies will struggle. Default rates on investment grade companies are typically much lower than in speculative grade (below BBB- rated). In their Default Study of last June[1], Deutsche Bank used S&P data to look at non-financial issuers and calculated how much compensation investors would have needed historically to compensate for five-year cumulative defaults in different rating categories using S&P data.

Going back to 1981, they conclude that in the worst year (1998) investors would have needed a 0.18% compensation for defaults that occurred over the next five years in A rated bonds assuming a 40% recovery rate, and 0.29% assuming a 0% recovery rate.

These numbers are substantially higher for BBB rated bonds, but still far below where current spreads are at 0.63% and 1.06% respectively, assuming 40% and 0%. This compares to 7.1% for High Yield in the year 2000, assuming a 40% recovery rate, and over 11.84% assuming a 0% recovery rate.

Downgrades in these periods often are clustered in one or more ‘problem’ sectors. In the 2001/2 TMT (technology media telecoms) crisis it was companies in those sectors, whereas during the GFC downgrades were concentrated around banks.

It is therefore of key importance to identify the sectors likely to be most affected and while we don’t know how the current situation will play out, we view sectors and companies that are highly energy intensive and cyclical as more at risk.

Managing uncertainty

Diversification is another way to manage uncertainty. During challenging times it is of key importance to not only diversify across names, but also to identify key credit drivers and avoid concentrated exposure to similar factors.

Looking at the arguments above, it is hard to see credit spreads tightening meaningfully as long as rate volatility stays this high.

For the European market, the tragic war in Ukraine adds a further layer of uncertainty and high energy prices are adding to the pressure to companies and consumers.

At the same time, the much higher credit spreads and overall yields already provide a substantial buffer for a further rise in yields. The investment grade universe consists of the larger banks and companies which tend to be more diversified and have stronger balance sheets, which should provide some resilience even in a recessionary environment.

Therefore, while we may see further negative returns in the near future, we continue to be constructive on the longer-term outlook.

[1] Deutsche Bank – Default Study 6 June 2022 figure 27