Key takeaways

- Chinese growth wedged between the hammer and the anvil

- Negative performance in credit so far due to duration rather than spreads

- How is the consumer feeling? Under pressure

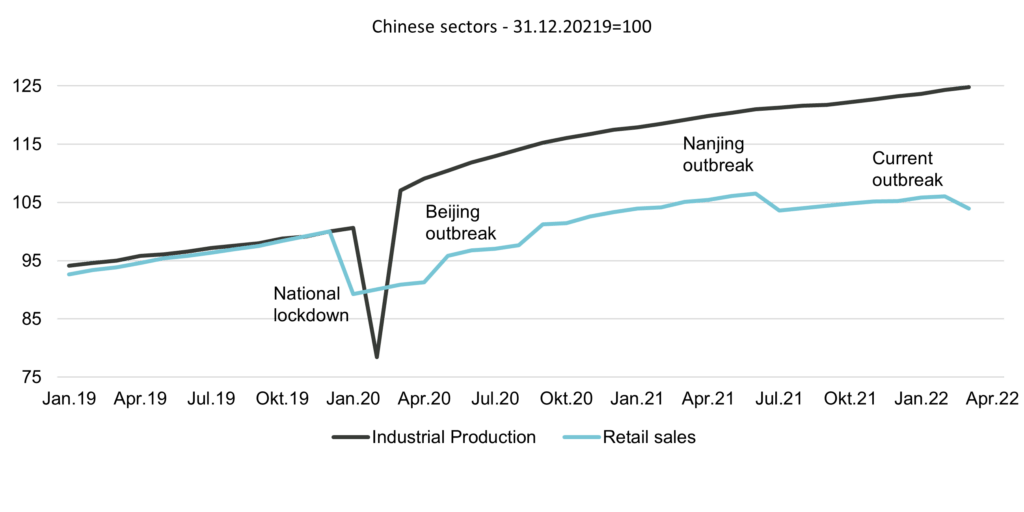

Covid outbreaks have hit retail sales rather than industrial production in China

A lot of data came out of China last week: credit and money supply, central bank decision, CPI, Covid, and growth for 22Q1. The growth data was solid, at +6.8% quarter on quarter, exhibiting a rebound. But at the end, economists further revised down their estimates for 2022, with the consensus now at 5%. The expansion of Covid on one side and the authorities zero-Covid policy on the other create frictions that are the main reason behind the deterioration in expectations about China.

The latest GDP contributions illustrate the current tensions. Fixed asset investment has been strong amid front-loaded policy support – and so has credit and money supply data for March. But end of quarter retail sales were weak and disappointed (-3.5% in March), feeling the strains of the latest lockdowns. April could be tougher – the graph above shows the impact of lockdowns. Furthermore, external demand, that supported the supply side during past outbreaks, is also slowing.

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) last week disappointed by not lowering its main policy rates, keeping it unchanged at 2.85%. Instead, the PBoC reduced the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) by 25 basis points, to 11.25%, freeing some liquidity. The rapidly narrowing spread with US Treasury yields and reversal in portfolio flows over the last months may be the explanation of this arbitrage.

Given current policies, more weakness in demand is ahead, and for the authorities the dilemma grows between introducing further costly (and inefficient?) support, or further relaxing some policies, concerning Covid but also the tech or housing sectors.

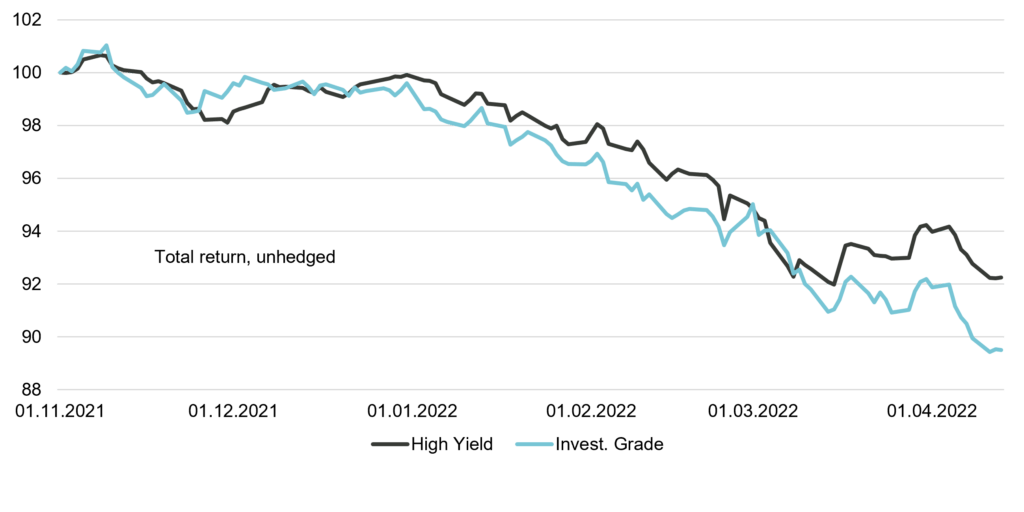

High yield (HY) performed better than Investment Grade (IG) since the Fed pivot

After the Fed announced its policy change in November, both high yield (HY) and investment grade (IG) globally took a hit as investors were pricing in more and more Fed funds hikes. Interestingly, HY performed better. Indeed, at the starting point, IG was probably more overvalued than HY.

However, the main explanation is the longer duration of the IG index, roughly two years. In other words, at this stage, a significant part of the credit sector’s poor performance is due to higher sovereign yields, not yet to spreads and credit risk. A look at corporate fundamentals confirms that balance sheets are still extremely healthy, and effective defaults still close to zero, even in the CCC bucket.

If the economy further deteriorates strongly and goes rapidly into recession – not our base case at this stage – of course HY will underperform, and investors should rotate toward IG.

Price moves did not differentiate between the two after the latest FOMC minutes or ECB meeting, both announcing less support in bond buying programs. It may still be a bit too soon to rotate and to continue preferring the spreads over the cycle. But the narrower the path for a soft landing becomes, the more the IG risk premia will become attractive, as well as cash of course.

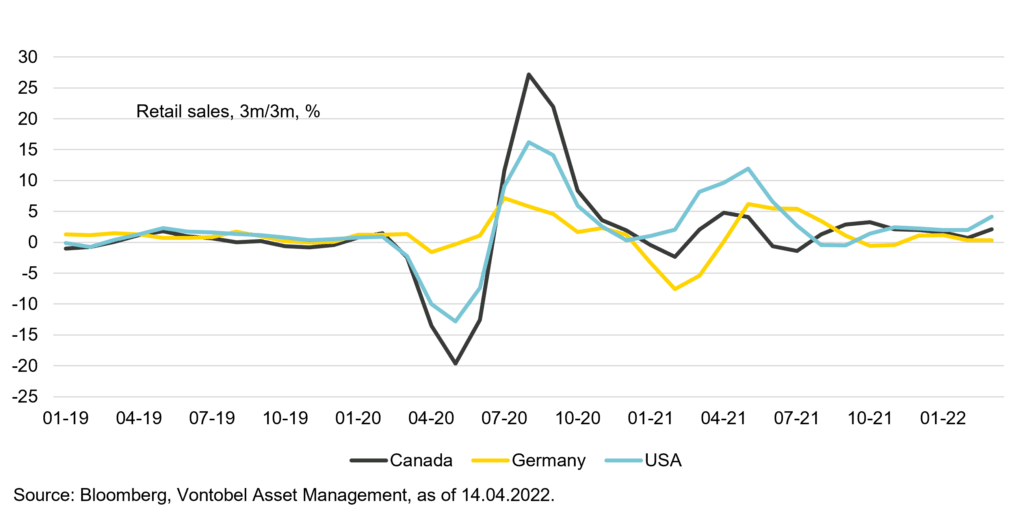

A resilient US consumer

With inflation at levels not seen for decades – around 7% globally at the end of Q1 – household purchasing power is under severe pressure. Conversely, healthy balance sheets and robust labor income should help households to absorb the shock.

March US consumers data sent positive signals from a cyclical perspective: confidence rebounded according to the University of Michigan, and retail sales were quite resilient, although the year-on-year pace continues to slow (quarterly pace in the graph).

But in other places, the picture looks less rosy. In China, consumption contracts (see above). Unsurprisingly, in Europe, consumer confidence plunged back to levels not seen since April 2020, with Germany being particularly at risk. And in many emerging countries, food prices, up by 30% over a year, raise all kinds of fears.

Given the unequal distribution in savings – as much as two thirds of developed market households may have put close to nothing aside during the pandemic – higher precautionary savings behavior could undermine soft landing expectations.