Many investors are not pricing in four risks in their portfolios. Each of these risks hurts DM bonds and currencies, but helps emerging markets bonds and currencies.

In January, the VanEck Emerging Markets Bond UCITS Fund was down 0.84% in January, compared to -1.27% for its benchmark, the 50% J.P. Morgan Government Bond Index-Emerging Markets (GBI-EM) Global Diversified and 50% J.P. Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index (EMBI). China was by far the biggest outperformer for the Fund, with Chile the largest underperformer. We increased exposure to Mexico and Poland local currency, covering an underweight exposure, and reduced our South Africa local exposure (where we now have zero exposure). We ended January with carry of 7.0%, yield to worst of 8.7%, duration of 5.8, and 52.7% of the Fund in local currency. Our biggest exposures are Mexico (local and hard), Brazil (primarily local), China (primarily hard), Colombia (primarily local), and Indonesia (primarily local).

| Average Annual Total Returns* (%) as of 31 January 2024 | |||||||

| 1 Month | 3 Month | YTD | 1 Year | 3 Year | 5 Year | 10 Year | |

| Class A: NAV (Inception 07/09/12) | -1.03 | 8.81 | -1.03 | 4.51 | -0.88 | 2.91 | 1.90 |

| Class A: Maximum 5.75% load | -6.72 | 2.55 | -6.72 | -1.50 | -2.82 | 1.70 | 1.29 |

| Class I: NAV (Inception 07/09/12) | -0.84 | 8.88 | -0.84 | 5.01 | -0.53 | 3.21 | 2.22 |

| Class Y: NAV (Inception 07/09/12) | -1.02 | 8.65 | -1.02 | 4.66 | -0.67 | 3.13 | 2.13 |

| 50% GBI-EM/50% EMBI | -1.27 | 8.27 | -1.27 | 6.56 | -3.37 | 0.23 | 1.85 |

| Average Annual Total Returns* (%) as of 31 December 2023 | |||||||

| 1 Month | 3 Month | YTD | 1 Year | 3 Year | 5 Year | 10 Year | |

| Class A: NAV (Inception 07/09/12) | 3.88 | 8.36 | 10.91 | 10.91 | -0.79 | 4.14 | 1.80 |

| Class A: Maximum 5.75% load | -2.09 | 2.13 | 4.53 | 4.53 | -2.73 | 2.92 | 1.20 |

| Class I: NAV (Inception 07/09/12) | 3.81 | 8.43 | 10.97 | 10.97 | -0.49 | 4.46 | 2.10 |

| Class Y: NAV (Inception 07/09/12) | 3.80 | 8.40 | 11.03 | 11.03 | -0.57 | 4.39 | 2.03 |

| 50% GBI-EM/50% EMBI | 3.97 | 8.63 | 11.95 | 11.95 | -3.31 | 1.46 | 1.71 |

* Returns less than one year are not annualized.

Expenses: Class A: Gross 2.55%, Net 1.22%; Class I: Gross 2.51%, Net 0.87%; Class Y: Gross 2.91%, Net 0.97%. Expenses are capped contractually until 05/01/24 at 1.25% for Class A, 0.95% for Class I, 1.00% for Class Y. Caps excluding acquired fund fees and expenses, interest, trading, dividends, and interest payments of securities sold short, taxes, and extraordinary expenses.

The performance data quoted represents past performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Performance may be lower or higher than performance data quoted.

The “Net Asset Value” (NAV) of a Fund is determined at the close of each business day, and represents the dollar value of one share of the fund; it is calculated by taking the total assets of the fund, subtracting total liabilities, and dividing by the total number of shares outstanding. The NAV is not necessarily the same as the ETF’s intraday trading value. Investors should not expect to buy or sell shares at NAV.

There are four unpriced risks to the bulk of investor portfolios, and each of these risks hurts developed markets (DM) bonds and currencies while helping emerging markets (EM) bonds and currencies. The four risks are the Fed/global rates, fiscal policy, geopolitics, and US politics. Markets historically tend to ignore three of these risks – fiscal, geopolitics, and US politics. Fiscal concerns (our “fiscal dominance” thesis, for example) are considered an almost heterodox worry. Geopolitics are considered unanalyzable. And analyzing US politics as having risky implications for the world is just not done (at most the investment conclusion redounds to defense stocks versus health care stocks). Our key conclusion is that emerging markets are on the winning side of these risks, as EM clearly has already-high real policy rates, good fiscal policy, is globalizing geopolitically (not de-globalizing), and is home to some of the most popular governments in the world (China, India, Mexico, Indonesia are a few examples of popular governments implementing orthodox policies).

Risk 1: Global interest rates (“the Fed”, if you will). Either way, EM wins and DM loses. When and if the Fed starts cutting its policy rate, EM bonds should perform better than most bond categories. In local-currency EM bonds (one half of our benchmark), this is because EM central banks raised their policy rates earlier and by more than the US. And also because the US dollar should start to decline as the Fed cuts rates, supporting EM currencies (i.e., not just their bonds). In hard-currency EM bonds, especially high yield sovereigns (the other half of our benchmark), the carry is so superior that it absorbs “sideways” or even weakness in risk-free rates. Put simply, if the Fed cuts don’t materialize, EM carry wins the day, and if they do materialize, EM will see bigger rates rallies than those in risk-free bonds.

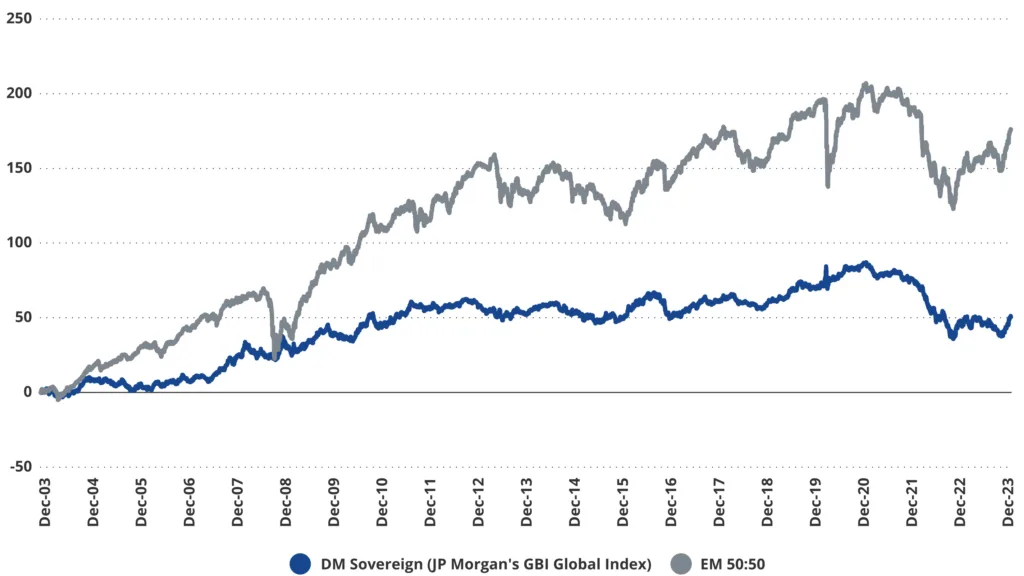

Risk 2: Fiscal risks in developed markets – DM is highly indebted, while EM is not. Our recent white paper, Fiscal Dominance: The Clarifying Lens for EM (and DM) Bonds goes through the full argument. In short, low debt levels in EM governments allow their central banks to solely focus on inflation, while high debt levels in DM governments force their central banks to focus on multiple objectives (not just inflation). This is no longer a theoretical point as popular media now regularly focus on US debt sustainability and the US’s rating by Fitch was cut to below AAA late in 2023 (S&P already had the US below AAA), and Moody’s has a negative credit outlook on its only AAA rating. Exhibit 1 shows the returns of two bond market, EM sovereign bonds (local- and hard-currency) versus DM sovereign bonds. This chart goes back 20 years. We also showed how the best within EM on fiscal metrics – Asian EM – actually became a flight-to-quality asset class during the past three years. The exhibit simply shows how superior EM government bond returns were compared to DM government bond returns. The argument we make in our white paper on the topic of “fiscal dominance” is that persistently good EM fiscal policy compared to persistently bad DM fiscal policy is the root of this big performance divergence. There are no indications that this is changing, if anything fiscal policy and anchored inflation expectations seem more labile than they’ve ever been. In any case, the premia in EM bonds more than reflects the real or perceived risks.

Exhibit 1 – EM Government Bonds Outperform DM

Bonds Performance EM Sovereign vs. DM Sovereign (total return, %)

Risk 3: Geopolitics favor an EM that is deepening globalization and a DM that is isolating. We also touched on this in our fiscal dominance white paper. Geopolitics have economic implications for EM and DM, and economics (in particular fiscal dominance) has implications for geopolitics. We’ve discussed particular phenomena in our previous monthlies. In general, the implications are:

- Higher defense spending in the DM, adding to fiscal pressure. DM defense spending looks set to increase due to geopolitical pressures. These add to the fiscal stresses in DM. If accompanied by higher inflation (often a symptom of war) and interest rates, the DM debt dynamic could begin to fray. U.S. deficits were forecast by the IMF to be in the 6%-8% range (above) before geopolitical risks became obvious to most forecasters.

- The Chinese renminbi (CNY) market share in international trade is low (at below 5%), but is in the top 4 (approaching the British pound) and rising. EMs are further integrating their economies, with finance a key focus. Saudi Arabia now conducts oil sales to China in CNY, India in Indian rupees (INR) with UAE, Saudi, and China with Brazil in Brazilian real (BRL), etc. Purchases of these EM currencies by central banks in the long run results in the purchase of EM bonds in these currencies (just as Saudi and Chinese reserves were accumulated in U.S. Treasuries because sales generated USD).

- Look for increased use of EM bonds as reserve assets, decreased use of DM bonds as reserve assets, prospectively. U.S./E.U./Japan, etc. (i.e., DM) sanctions freezing the Central Bank of Russia’s reserves of Treasuries (and Japanese Government Bond, etc.) has forced all EM central banks to reconsider their reserve holdings in light of this new fact. Reserves should not be subject to sanctions risk from the perspective of EM reserve managers, for whom reserves are a nation’s safety net that should by definition should be “risk-free”.

- “Stagflation” that helps EM and hurts DM appears to be a real long-term scenario. Supply risks and greater economic integration in EM mean that rising commodity prices are likelier, and have a differential impact – India and China paying a different (and unknown) price for oil than do the DM is a glaring example. EM (defined by EM bond indices) include many commodity exporters, which can benefit in this scenario. DM are largely commodity-importing.

These implications will take many years to play out, but they represent a long-term tailwind for EM local-currency bonds. As we showed at the outset, it is the deficit-producing DMs that need financing from the surplus-producing EMs, whether the situation is understood that way yet, or not. The fact that EM and DM are increasingly in geopolitical disagreement represents an obvious global market risk. It is risky to depend on adversaries for one’s financing is a sentence that shouldn’t need to be written, but here we are. EM central banks will increasingly want reserve assets backed by high real yields and debt sustainability, with zero sanctions risk. Central bank purchases of gold are by now well-reported and known, especially the fact that now both EM and now DM central banks are buyers. Gold is the easiest first-reaction from central banks. But, bonds with yield and currencies with use in trade are the ultimate desire for reserve managers and they will find these in EM local-currency bonds. As noted earlier, this is a long-term tailwind, not translating into a straight line. In particular, the USD has a key structural support – most global debt is denominated in USD. This means that “risk-off” translates into USD-up1. This is less-and-less the case, as we show above with Asian EM local currencies rallying during the U.S.’s fiscal and banking issues in 2023, for example. There, countries that proved their fiscal and monetary rectitude over decades rallied as DM bond markets suffered. Put differently, the USD-up is increasingly only up against the other DM currencies and the riskiest EM currencies, not against the best EM currencies. Anyway, our general point is that even geopolitical developments that are getting increased attention support our fiscal dominance thesis.

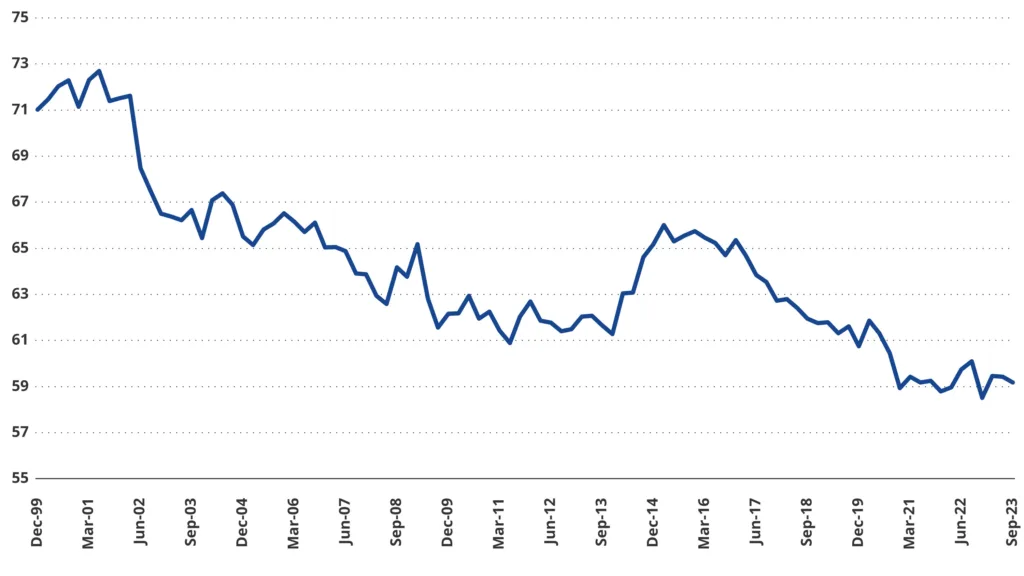

Exhibit 2 – Central Banks Hold Fewer Treasuries

Foreign Exchange Holdings in U.S. Dollars, % of allocated reserves

Risk 4: US politics. Market participants are especially loath to discuss politics given obvious fractiousness in DM societies. And this is on top of the normal bias in DM markets that politics simply don’t matter. We saw glaring examples of this in Brexit and President Trump’s election in 2016, both of which the “cool kids” said would never happen. The key takeaway here is that US (and European, for that matter) politics are becoming important market drivers for DM. Former UK Prime Minister Truss lost her job after 90 days due to a fiscal/bond market crisis created by the UK’s fiscal dominance (and her policies’ inability to comfort the market) less than two years ago! Ignoring things you don’t like or don’t want to talk about is unacceptable in risk management, of course. The flip side is that politics have normalized in most of EM, with voters more-or-less seeking to optimize economic outcomes in a disciplined policy context. This is arguably the case in large countries including Indonesia and most of Asia, Mexico, Colombia, China, Poland and many others. This is quite different from the constraint-free policy environment in the US where “deficits don’t matter”. With sanctions against countries’ holdings of US treasuries a policy tool, it should not be hard to imagine what happens after sanctioning one’s lenders, especially when one runs big deficits (see Exhibit 2).

EXPOSURE TYPES AND SIGNIFICANT CHANGES

The changes to our top positions are summarized below. Our largest positions in January were Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia, and Poland:

- We increased our local currency exposure in Mexico and Poland. Poland’s strong institutions providing protection against political noise. Poland’s central bank is currently on hold giving the new government space to sort out its post-election fiscal priorities. Mexico’s bonds are even more attractively priced. Mexico’s central bank is also on hold – waiting for inflation to get closer to the target range (and for the pre-election fiscal plans to get clearer) before starting its easing cycle. These considerations improved the policy test scores for both countries.

- We also increased our local currency exposure Brazil, and hard currency corporate exposure in Brazil and Thailand. Brazil’s local bonds are among the most attractively priced in major EMs. The central bank’s easing pace is cautious and steady (-50 bps per meeting), as there are some residual concerns about the 2024 fiscal outcomes. The reason for adding corporate exposure in Thailand was meeting our risk limits in a situation when local bonds do not look attractive.

- Finally, we increased our hard currency sovereign exposure in Bolivia and local currency exposure in Uganda. Uganda’s valuations look very attractive, inflation is low and the central bank is not in a hurry to ease. There was also more progress in the oil sector, especially as regards the refinery construction after the government signed a memorandum of understanding with the UAE, improving the economic test score for the country. In Bolivia, a lot of risks appear to be priced in, while the government’s external debt is low and a big part of it is official. The political noise will persist going forward, but some risks moderated following the constitutional court’s decision to ban indefinite re-elections, improving the policy test score for the country.

- We reduced our hard currency sovereign exposure in Chile, Malaysia, and Egypt. Stretched valuations played a big part in our decisions regarding Chile and Malaysia. In Egypt, our main concern was the impact of the Red Sea shipping disruptions on Egypt’s FX revenue/inflows, which worsened the economic test score for the country.

- We also reduced our hard currency sovereign and local currency exposure in South Africa, and hard currency corporate exposure in Burkina Faso. The company CEO’s questionable activity was the main reason in Burkina Faso. In South Africa, political noise is bound to intensify in the run up to the elections, potentially affecting domestic sentiment, growth, and as a result the fiscal performance, worsening the country’s economic and policy test scores.

- Finally, we reduced our hard currency sovereign exposure in Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, and Cote d’Ivoire. Cote d’Ivoire valuations look stretched, worsening the technical test score for the country. In Bahrain, we are concerned about the impact of weaker hydrocarbon production and the Red Sea disruptions on growth, which worsen the economic test score against the backdrop of significant external debt obligations. Oman’s trade balance is supportive, but a lot of good news (such as a potential upgrade to Investment Grade) appear to be priced in. Qatar valuations look less attractive after the rating upgrade.