Fixed income portfolio managers Seth Meyer and Tom Ross note how low primary supply (new issuance) in the high yield bond market is providing some support for high yield bonds at a time when the asset class is being pressured by inflation and growth concerns.

Key takeaways

- 2022 is shaping up to be a slow year for primary supply and there is little to suggest a sudden rush of issuance given many borrowers have already refinanced.

- There are pros and cons from a weak primary market in that it helps balance supply against weaker demand but longer term it could be disadvantageous to diversification and even contribute to higher volatility by reducing confidence in market prices.

- With central banks stepping back from net asset purchases the softening in supply may be timely, although quantitative tightening is arguably more of a concern for European credits than the US.

Faced with a wait of several months for a new car? You are not alone. Unless you are prepared to snap up the model in the dealer’s showroom, the wait time for even the more basic models can run into months. Order backlogs have been amplified by production delays as COVID lockdowns and the conflict in Ukraine impacts the supply of critical parts. But supply constraints are not just restricted to the physical economy, we notice them in the financial world too – and one area of fixed income with limited supply recently has been high yield bonds.

Dearth of supply

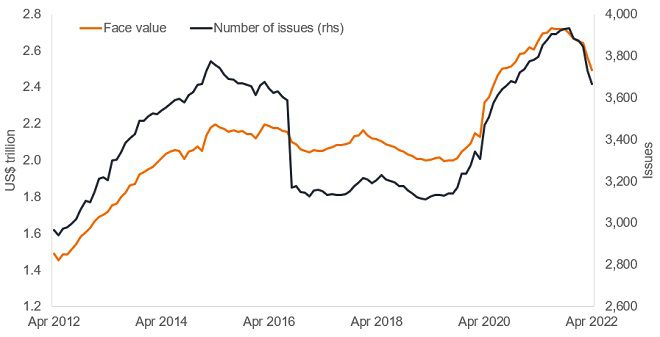

Primary issuance in high yield has been particularly weak. In the US, the first four months has been the slowest start for more than a decade and expectations are that the total for the year could be similarly weak.

Figure 1: 2022 shaping up to be a slow primary year for US high yield

The lack of supply is just as stark in Europe where just one deal worth €465m was issued in April. In the first four months of 2022 just €13 billion of non-financial high yield bonds have been issued, marking a 73% fall on the same period in 2021 and the weakest pace of European high yield issuance since 2016.1

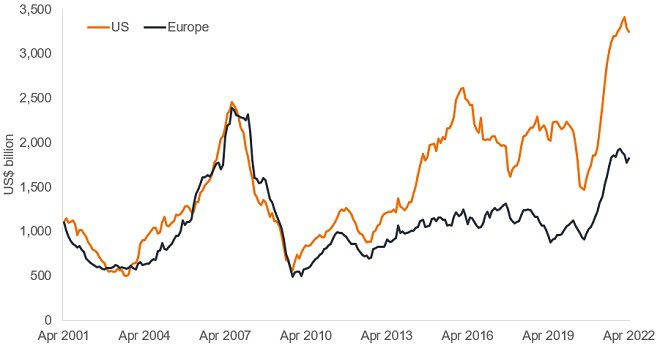

Feast to famine may be a little strong but issuance was always likely to slow – what has caught the market by surprise is the extent of the slowdown. Lest we forget 2020 and 2021 were decent years for growth in the size of the high yield market. This reflected a number of factors:

- Existing issuers needing to borrow to cover revenue shortfalls caused by lockdowns

- Investment grade companies being downgraded into the high yield universe

- First time issuers coming to the market, typically at the intermediate stage of growth where more meaningful debt capital was required to finance expansion.

This contributed to a rise in the overall size of the high yield market, with both total face value and the number of bonds in issue growing.

Figure 2: High yield market expansion and contraction

Recent months have seen something of a reverse. Partly, this is something to celebrate. Several large high yield issuers have become ‘rising stars’, progressing up to investment grade status. Familiar names making this move in recent months include Kraft Heinz, the food group, and Freeport-McMoRan, the miner.

Corporate borrowers are opportunistic. In many cases, there is simply no need to borrow more when they did all the financing they needed to do during and in the aftermath of the COVID crisis. After all, it made financial sense to issue bonds last year when rates were low. Cash balances today are relatively high and without pressing expansion projects we should expect companies to be patient.

Added to that has been a recent slowdown in merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, which usually needs financing. This is actually a welcome development from our perspective as we were beginning to worry that corporates were starting to exhibit bondholder-unfriendly behaviour, with more issues linked to leveraged buyouts and takeovers. Judging how the recent volatility in equity markets will play out for credit is challenging as it can both decrease enthusiasm for M&A by encouraging boards to preserve cash or increase it as lower equity prices can spur opportunistic takeover bids and share buybacks.

Figure 3: M&A transactions are starting to slow (12-month rolling total)

Should we be concerned by weak issuance?

There is a danger that corporate borrowers backload more of their borrowing for the latter part of the year. For example, as Figure 1 demonstrated earlier, 2016 started off slowly but an acceleration later in the year led to a pick-up in issuance, although the annual total was still below average. This would require surprise borrowing, however, as the maturity profile of existing bonds means there is no pressing refinancing need that would suggest a wall of issuance near term. Central bank policy tightening and concerns about a possible slowdown in the economy are also unlikely to encourage companies to take on unnecessary borrowing.

Low primary issuance can be frustrating for investors as it is often a fruitful way to gain access to a borrower’s bonds. To encourage take-up, new issues typically come at a small price discount (or yield premium) to an issuer’s existing bonds in the secondary market so fewer new issues lessens the opportunity to potentially benefit from this. That being said, a new issue yield premium alone is not reason enough to invest in a bond so investors still need to do their homework on the fundamental strengths of the issuer and the bond’s valuation. A more valuable role for new issuance is that of diversification. A pipeline of new issues helps ensure the asset class does not become stale. We want to be able to hold securities across a range of companies to diversify risk so over time it is healthy to have companies using the bond market to raise capital.

The other key advantage of new issuance is it both acts as a sign of confidence and provides useful price signalling or discovery. Regular supply of new issues can help market participants gauge whether the pricing in secondary markets is fair. Fewer new issues mean fewer opportunities to benchmark existing bond prices against what the market is prepared to pay for new issues, which in turn can lower confidence in prices and contribute to higher volatility.

On the plus side, lower supply does mean there is less technical pressure that could drive credit spreads wider as demand and supply are more likely to be in equilibrium.

It takes two to tango

The other side of the ledger is demand. Borrowers are more inclined to issue if they can do so at low cost (i.e. low yields) when there is strong investor demand. Recently, that demand has been weaker. Greater risk aversion from investors has seen outflows from high yield funds, particularly among exchange traded funds (ETFs). Concern about inflation has also meant loans (an alternative way of raising debt capital) have been popular with investors given they typically have floating rates where the coupon or interest paid on them rises as interest rates rise.

Added to this, several central banks are moving away from quantitative easing towards quantitative tightening. This is going to remove large price insensitive buyers from corporate bond and sovereign bond markets. As part of their asset purchase schemes, central banks have been active in the investment grade corporate bond markets, particularly in the UK and Europe; although high yield bonds have not typically featured in these schemes there is potential for pass through of spread widening if the withdrawal of central bank support diminishes risk appetite. This is potentially less of a direct concern in the US where asset purchases have been directed principally at sovereign bond and mortgage-backed securities, although there could still be spillover effects. How central banks engage in quantitative tightening – either passively by allowing bonds to mature and not reinvesting or actively by selling securities to accelerate their balance sheet shrinkage – will have a bearing on how credit markets react.

We recognise that there may be some tricky months ahead for high yield bond markets, but with yields higher across the board and supply technicals favourable, this could help mitigate some of the widening pressure on spreads arising from concerns about the economic growth outlook. We might moan about the weak supply but right now it is proving timely in helping to offset some of the softening in demand.

Terms

Credit spread: The difference in yield between securities of similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

Diversification: A way of spreading risk by holding different securities or assets. It is based on the assumption that the prices of different securities or assets will behave differently in a given scenario.

Exchange traded fund (ETF): A security that tracks an index (such as an index of equities, bonds or commodities). ETFs trade like an equity on a stock exchange and experience price changes as the underlying assets that comprise the ETF move up and down in price.

High yield bonds: Also known as speculative grade or junk bonds, these bonds involve a greater risk of default or price volatility and can experience sudden or sharp price swings. These bonds carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher coupon in recognition of the additional risk.

Investment grade: A bond typically issued by governments or companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments. The higher quality of these bonds is reflected

in their higher credit ratings.

Leverage: The level of indebtedness of a borrower. Higher leverage means higher debt levels. A leveraged buyout is the purchase of a company mainly financed by borrowing or issuing debt.

Mortgage-backed security: A security which is secured (or ‘backed’) by a collection of mortgages. Investors receive periodic payments derived from the underlying mortgages.

Primary issuance/market: This describes bonds that are issued for the first time; the secondary market describes bonds that are already in issue.

Quantitative easing: An unconventional monetary policy used by central banks to stimulate the economy by boosting the amount of overall money in the banking system. A key method has been to create money and use this to purchase securities such as bonds. Quantitative tightening is the reverse where the central bank shrinks its balance sheet and the money supply by not reinvesting the maturing securities it holds or actively selling them.

Share or stock buybacks: Where a company purchases its own shares. This has the potential benefit of supporting the share price given that earnings are spread over fewer shares. While potentially good for shareholders, for bondholders it can be less welcome as it can mean less cash or equity capital in the business.

Technical: the demand and supply conditions within the market for an asset class or a security and the behaviour of market participants.

Volatility: The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index, moves up and

down. Volatility measures the dispersion of returns for a given investment

Yield: The level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate. At its most simple for a bond this is calculated as the annual coupon payment divided by the current bond

price.