In 2019’s paper A Case for Growth, I argued that, despite a decade-long run for growth stocks, there were plenty of exceptional growth companies left for long-term investors to pick from. The cupboard was by no means bare. Two years on, has our thinking changed?

The implications of today’s great new networked infrastructures – the Internet and the Cloud – still exceed our comprehension.

Their hyper-connectivity plants the seeds for power laws – the capture of a large percentage of returns by a small percentage of companies – to form, leading to winner-takes-most dynamics in more and more markets, many of which are still germinating.

The further connection of mankind, and the resulting easier transmission of ideas, will feed our imaginations and unleash previously unthinkable innovation.

In 2019’s paper A Case for Growth, I argued that, despite a decade-long run for growth stocks, there were plenty of exceptional growth companies left for long-term investors to pick from. The cupboard was by no means bare. Two years on, has our thinking changed?

Well, yes it has. We’re even more enthusiastic, even more convinced by that thesis.

Readers might recall that the star of the previous story was disruption. Disruption and growth opportunities go hand in hand, and the past two years have only brought more of the former.

We’re living in a period of unprecedented disruption. To support this assertion, we’ll again draw from Peter Drucker’s seven sources of innovation. Drucker posited that any one of the sources listed below would be enough for an imaginative, resourceful entrepreneur to build a business on – and to grow that business. But what is remarkable is that today, each of the seven are in play at the same time.

Peter Drucker’s Seven Sources of Innovation

Source of Innovation

Drucker’s Description

Active Today?

Industry Structure

Changes in industry structure that catch everyone unaware.

Internet + Cloud

✓

The Incongruity

The gap between reality as it actually is and reality as it “ought to be”. I.e. dislocations between supply and demand.

Bezos’ “Divine Discontentment”

✓

Process Need

Perfecting, re-designing, or correcting a weak link for a process that already exists. Falling cost of tech → AI, automation, etc.

Falling cost of tech → AI, automation, etc.

✓

New Knowledge

Both scientific and non-scientific.

New data → New insights

✓

The Unexpected

The unexpected success, failure or outside event.

Covid-19 and “Accumulated Accidents”

✓

Demographics

Predictable changes in population.

“Ok boomer”

✓

Zeitgeist Shift

Changes in perception, mood or meaning.

“Win at all costs” → “Stakeholder success”

✓

Source: Drucker, Innovation & Entrepreneurship, 1985.

In A Case for Growth, we elaborated on one of these forces: incongruities. Today I want to study another: changes in industry structure.

There are two once-in-a-lifetime changes happening here, affecting two separate industry structures. Between them, they affect almost every corner of society and the economy:

- The internet as the infrastructure upon which commerce, media and information flow

- The cloud as the infrastructure upon which IT is stored, powered, and distributed.

I suspect you’re thinking: “The internet and the cloud? Old news!” That’s fair. But I’d assert that their implications are still deeply underappreciated. As infrastructures, the changes they instigate are deep and far-reaching. And perhaps more interestingly, the arrival of these new infrastructures causes profound knock-on effects which impossible to fully grasp, and which are set to play out for decades. Because disruption begets more disruption.

The Scope of Their Impact: Pace Layering

In 2000, Stewart Brand wrote The Clock of the Long Now. He described it as a book about time, responsibility and how civilizations that think about the long term tend to be healthier and “better at looking after things”.

If you are an investor – or an individual – who thinks in decades as opposed to quarters, the book will likely strike a chord. That said, my goal here is not to elaborate on Brand’s view on time and humanity (virtuous as it is), nor is it to weigh in on his thinking about responsibility or the evils of short-termism (spot-on as that seems). Rather, it is to draw from one of the frameworks he introduces, and to use it as a lens through which to view this source of disruption. He calls the framework ‘pace layering’.

An important clarification: there is precisely zero mention of investing or business analysis in The Clock of the Long Now. Stewart Brand focused on helping civilization, not on analyzing businesses or business models. But that’s exactly what Pip Coburn and I did at Coburn Ventures, after seeing how far-reaching the Pace Layering model was.

Because at its core, the Pace Layering model is about how systems work and how the different entities that make up the system interact. And while Brand applies it to the health of one system (civilization), it’s also very relevant to others, such as the economy and the businesses that comprise it.

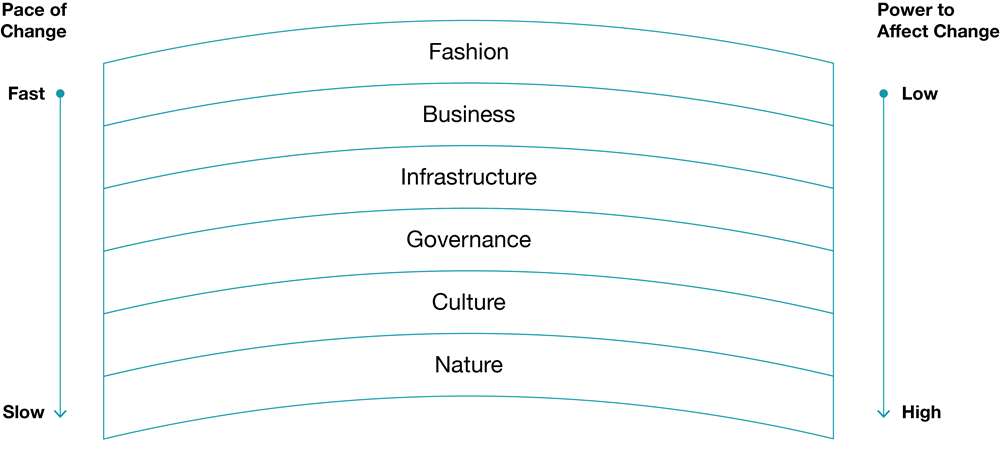

Now, about that model. Brand suggests that society is composed of six layers: fashion, commerce, infrastructure, governance, culture and nature. From there, he offers three key insights: one involving pace of change, one involving interdependence, and one involving power.

Stewart Brand's Pace Layers

The Clock of the Long Now, Stewart Brand, 1999 and Coburn Ventures.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance

- Pace of change: The layers change at different paces, with the upper layers changing more frequently than the bottom layers.

- Interdependence: The layers are related to each other. A shock to one layer sends ripples through the system.

- Power: Society tends to focus on the fast-moving layers, but the slow-moving ones have the power. They tend to control and constrain the fast-moving layers.

Ok, so what does this all have to do with the internet, the cloud and disruption?

Most of the change we observe around us happens in the top two layers: fashion and business. Noticeable, but with few significant long-term implications. However, the internet and the cloud represent Infrastructure change-outs. These are rarer. But when they happen, the consequences are more profound. When a new infrastructure emerges, the change reverberates across the entire system, but the most direct impact is on the layer that sits atop infrastructure: commerce. Meaning the businesses we invest in.

Investment Implications:

- We should seek companies that have become infrastructure themselves¹ and patiently hold them for a very long time. Examples include Amazon, Shopify and Illumina. These may not seem fresh ideas, but their infrastructure position confers an enduring edge (since infrastructure changes relatively infrequently) and the power to control commerce that sits on top of them, potentially expanding their addressable markets.

- We should seek companies leveraging new infrastructure to disrupt incumbents that build their businesses on old infrastructure in big markets, and can do so for very long periods of time, e.g. cloud software such as Snowflake.

- We should identify companies that are laying down what will become the vibrant infrastructures of tomorrow, e.g. Doordash’s last mile logistics network.

- We should identify large pockets of the economy that were previously inert but which will eventually be affected by the new infrastructures, e.g. education, healthcare, and transportation seem ripe for the picking.

1. Defined as something required for the healthy operation of a system. It can be physical, habitual, or a simple reflection of an entity’s importance to its system. A fad must be liked, while an infrastructure must be required.

Knock-on Effects: Pareto vs Gauss

These new infrastructures have a characteristic that creates knock-on effects whereby disruption begets more disruption. They are hyper-connected networks, and networks can lead to extreme events. In investment terms they’re ‘outliers’.

I’ll elaborate. In 2011 Edge.org posed the following question to over 150 leading thinkers: What scientific concept would improve everybody’s cognitive toolkit?

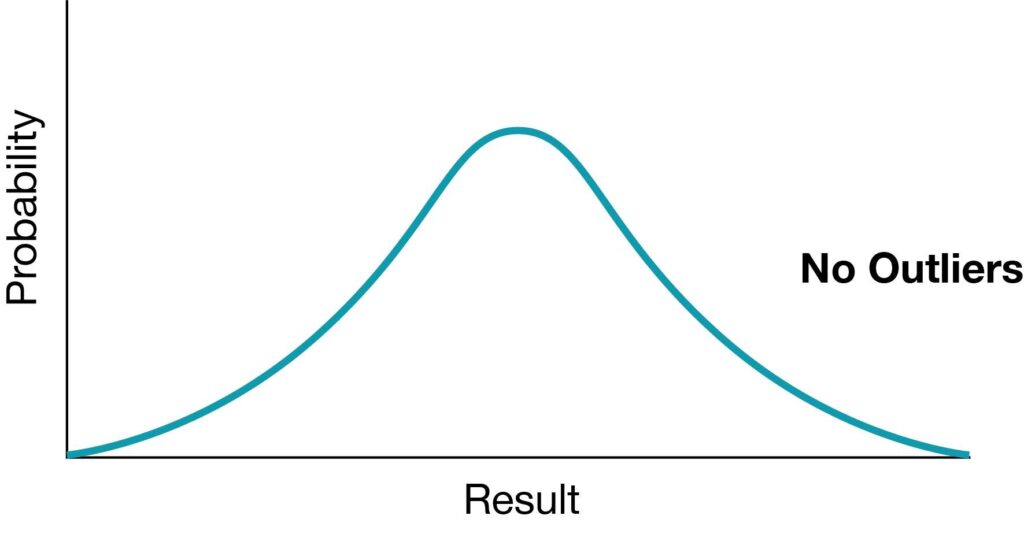

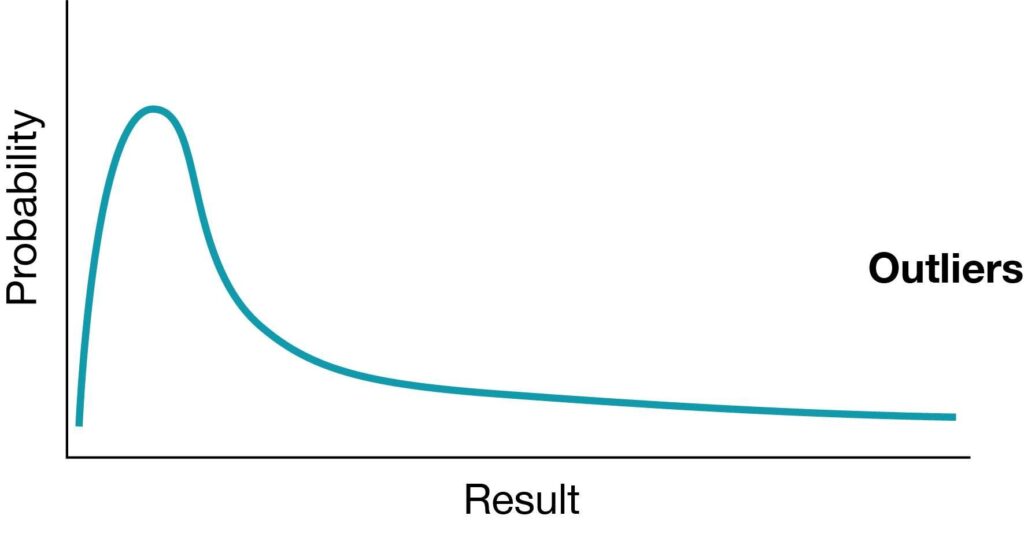

One answer resonated loudest: The Pareto Principle. Here, Clay Shirky pointed out the strangeness of still viewing the world through a Gaussian (bell curve) lens. Why are we still surprised by extreme events? Why do we consider them anomalies when, in fact, the natural order of things is often Paretian (80/20 rule, or winner-takes-most) and which fully expects such things to take place?

The passage got me thinking a bit about Gauss and Pareto. For starters, this thread shines a light on one of the more powerful elements of Baillie Gifford’s ethos. We seek outliers, and our drive for asymmetry aligns us more closely with the spirit of Pareto than most. But is there more to understand as we search for outliers and extreme events?

Gauss

Normal Distribution

The world we often expect: Gauss

- Bell curves

- Averages

- Independent

- Bulk Processing

- e.g. Height

- e.g Rolling dice

- e.g. Shoe size

Pareto

Power Law

The world we increasing live in: Pareto

- Power laws

- Winner takes most

- Inter-dependent

- Information/data flow

- e.g. Social networks

- e.g. Size of cities

- e.g. Magnitude of earthquakes

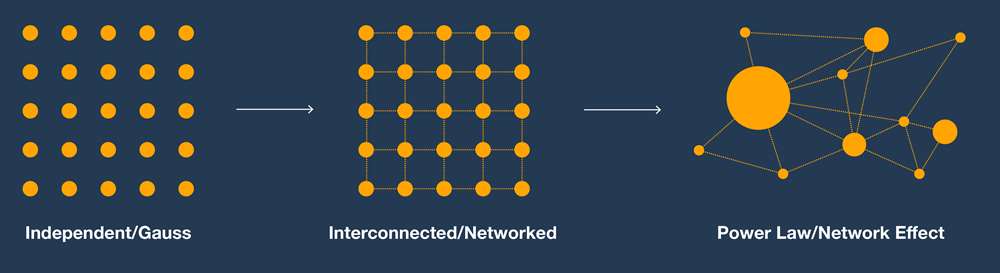

My answer to this question involves phase shifts. Specifically, a phase shift that takes a system (e.g. a market structure) from a Gaussian distribution pattern to a Paretian one.

For those of us who traffic in disruption, asymmetry and outliers, there’s nothing so adrenaline-boosting as knowing when a system (e.g. a market) might transform itself from linear distribution (Gaussian) to a power law (Paretian), potentially leading to a ‘winner-takes-most’ dynamic.

This begs the question: what can we do to better understand the root cause – the precondition – that takes a market and morphs it from Gaussian to Paretian? Intuitively, many of us will respond “network effects, of course!” But this answer – while simple and accurate – somehow feels incomplete.

When Independence Turns to Interdependence

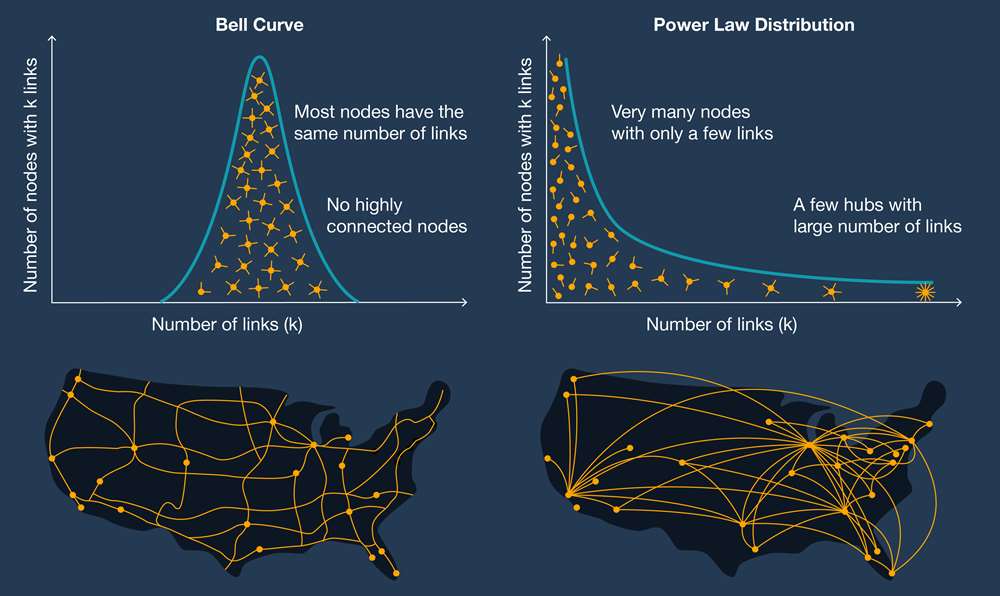

I found the work of Bill McKelvey, former Professor of Strategic Organizing and Complexity Science at UCLA Anderson School of Management, instructive here. He broke down the mechanics behind the formation of Paretian systems and power laws in a helpful (and thankfully accessible) manner. Put simply, a system morphs from being Gaussian to Paretian when the agents within said system lose their independence and become connected. As Professor McKelvey puts it:

“Our review of the different kinds of power law phenomena shows that underlying each is a collapse of the independence assumption. Once independence among data points collapses, and interdependence or interaction occurs, then the seeds of power law formations are planted. It is just a matter of time, just a matter of probability, for interdependent events to progress – from positive feedback effects – into an extreme event.”

In a way, he’s simply expressing in different words something many of us intuitively understand (ie the power of being networked). But there is something about his viewing of the agents inside a system as losing their independence that unlocks an insight for me. Applying this thesis to some powerful – and well understood – examples from our recent past illustrates the potential power of that transformation.

There are lots of ways to explain the (asymmetrical) success of internet platforms over the last 15 years, but it’s clear that web-enabled interconnection is at the heart of it. Blockbuster video stores were largely independent of one another whereas Netflix is part of an interconnected ecosystem. Ditto for Circuit City and Amazon, for Yellow Pages and Google, and so on.

How about Apple? Sure, there was the Steve Jobs halo effect. But in hindsight it’s easy to see how the iPhone platform was an interconnected system where data flowed freely whether it was the payment from my bank to the app store or the GPS data ingested by Waze to help me find my way around a traffic jam. It’s also easy to see Nokia and Motorola through this ‘independent’ lens. They had scale. They had brand. They had technology. But relative to Apple, their independent nature is clear. They were of the Gaussian world.

But wait. Weren’t Nokia and Motorola phones connected? Weren’t they part of a network? Well, yes they were, but here we must acknowledge the varying degrees of interconnectivity, as this illustration from AL Barabasi’s 2003 book Linked: How Everything is Connected to Everything Else shows. The infographic reveals that the outliers in a power law distribution have more links than the nodes with one link. They are ‘hubs’. By contrast, a bell curve distribution has many nodes that have the same number of links but none that have significantly more. So while Nokia phones (and Circuit City stores) were, in a sense, connected, both the number and types of agents connecting to it were very different from their equivalents at Apple, who attracted arguably the most important set of ‘agents’ into its platform: the app developers.

If you look closely, you’ll notice a neat tie here back to the Pace Layering model. The hubs – those hyperlinked nodes inside a system that become invaluable to other less powerful nodes in the system – become infrastructure. By Brand’s definition, that translates to durability, and power – the power to grow even larger.

The larger point here is that these companies – the so-called FANG stocks – are often thought of anomalies. Outliers. And to some degree they are. The result of extraordinary vision, powerful strategies, superior business models all coming together. But I’d argue that the extreme nature of their success – their “winner takes most”ness – could simply not have happened if not for the networked nature of the systems in which they participate. It is the networked system that allows for any of this.

And here’s the punchline: that system, that hyper-connected network isn’t confined to so-called FANG stocks. It’s everywhere. And it sets the table for more outliers to emerge. We suspect some are still just germinating.

Power Law Enablers: Interconnectivity and Information

As you may have guessed, this interconnectivity has implications for the cloud as well. While saying the cloud represents a big disruption might seem like stating the obvious, I question whether it has been fully considered through this Paretian lens. But there is a strong case to make that just as the Internet provided the ‘connection’ that morphed Blockbuster’s Gaussian independence into Netflix’s Paretian interconnection, the Cloud is doing the same to enterprise infrastructure. It represents the creation of a massive, centralized repository where the world’s data and applications can reside and, yes, interact.

There are new hubs with hundreds of thousands of spokes coming off them in the cloud. That’s to say, it represents one big phase shift from independence (ie on-premise) to interconnection. Along the way, the seeds are being planted for power laws to take hold.

So What Are The Investment Implications?

For starters, this question will remain front of mind in my research agenda for the next decade:

Which systems are about to go through a phase shift whereby participants will inevitably transform from independent to interconnected? What are the new hubs?

It may seem like ‘everything’ is now connected, but there are still systems that have yet to transform (or are at least at an extremely early stage). Gyms → Peloton. Used car dealerships → Carvana and Vroom. Databases → Snowflake. Internal combustion cars → Tesla. Indeed, this Paretian lens is a particularly useful tool to have handy for optimists – like Baillie Gifford – who ask not what ‘will go wrong?’ with a company but rather ‘what could be possible’ if things go particularly right?

These companies already seem wildly successful, but what if a power law is now forming inside each of their markets, none of which have ever seen anything like a power law?

The New Cargo: Ideas and Ingenuity

One final knock-on effect to consider:

If we break down the key jobs any network does, access and transport (or transmit) will be near the top of the list. From this premise, I’d argue that the value of the network – or its disruptive potential – is related to the nodes it connects and to the resources that are being transmitted as, for lack of a better word, cargo.

But bringing this back to the real world, let’s reflect on the impact that a famously powerful ‘new infrastructure’ such as the transcontinental railroad had in the US in the mid-19th century. Its nodes were towns and ports. Its cargo was freight and people. All things of the material world. Finite. Yet it supercharged American industry. No mean feat!

Contrast that with the nodes and cargo of today’s new infrastructures. Its nodes are – theoretically – every human and any machine connected to it. And instead of transporting people, cattle, and crops, today’s networks transport bits and bytes. Not merely ‘data’ but also software and applications, the very vessels for ideas and human creativity and ingenuity. The difference involves – as Nobel Laureate Paul Romer famously theorized – the non-rivalrous and infinite nature of ideas, the accumulation of – and sharing of – which leads to growth and progress (not just raw materials, capital and labor as the classic view of economics held).

The power of all this is expressed well in Paul Graham’s excellent essay ‘Great Hackers’. He writes “In a low-tech society you don’t see much variation in productivity. If you have a tribe of nomads collecting sticks for a fire, how much more productive is the best stick gatherer going to be than the worst? A factor of two? Whereas when you hand people a complex tool like a computer, the variation in what they can do with it is enormous.”

As I read that, the question that pops to mind is “what tool is even more complex than a computer? Where can the variability be even greater?”. The answer, I think, lies inside our own heads and hearts: imagination, creativity, human ingenuity.

This is the new cargo. Ingenuity that creates the software to allow for the re-use of rockets at SpaceX; that sequenced the virus behind a global pandemic and identified a solution as rapidly as Illumina and Moderna did; that delivers medical supplies via drone in Rwanda as Zipline does. We could go on. Thanks to these new infrastructures, the tools are at hand for the entrepreneurial minded to address problems never before addressable, with creativity and imagination that are – for the first time in human history – transportable in real-time and on a global scale.

Most exciting of all: as more and more humans are exposed to these tools, we – the network nodes – will change. With each new breakthrough innovation, the impossible will seem a bit more possible. Our imaginations will be fed. Just as Google trained us to ask more questions by giving us access to any question imaginable, these tools will inspire more and more of us to identify the next problem to solve –and work on creating the solution.

As a growth investor, it’s (still) hard not to be excited about the opportunities ahead.