India could be poised for double-digit growth

The last decade has been challenging for India’s manufacturing, construction and infrastructure sectors as the investment cycle slowed down. That weighed on gross domestic product growth, which reached a decade-low 4.2% in 2019. Consumer demand driven by easy finance, runaway credit growth for an aspirational population, and government spending have been key supports for economic growth. So what are the prospects for India’s market and economy?

In our view, industrial firms’ aggressive cost-cutting during the past few years has laid the foundation for change. Companies have slashed capital expenditures and reduced leverage. The Indian government has implemented much needed labour reforms. Meanwhile, bank balance sheets are healthier and interest rates are low. Against this backdrop, Indian manufacturing is probably entering a multi-year growth period with recovery in margins, profits and ROCE (return on capital employed). This should drive the new investment cycle.

At the same time, the COVID-19 vaccine rollout is restoring consumer confidence. India has navigated the pandemic well despite dire forecasts. After what has been dubbed the harshest lockdown in the world, the economy has bounced back more quickly than expected.

In our many conversations with companies, we sense a buoyancy in corporate and entrepreneurial sentiment that has been missing for the past few years. Various sectors of the economy have begun to normalise. Manufacturing activity, export orders and property and vehicle sales have all improved.

The government’s approach also appears to be shifting. Rather than trying to clean up the system, as it has done with significant success over the last six years, it now seems to be targeting growth and wants to work with the private sector to spur the economy. Case in point: India recently unveiled a production-linked incentive programme to encourage foreign manufacturers of mobile phones, pharmaceuticals and medical devices to set up shop in the country and for domestic producers to expand. The just-released central government budget for the 2022 fiscal year, with its focus on infrastructure spending and growth, has further buoyed sentiment.

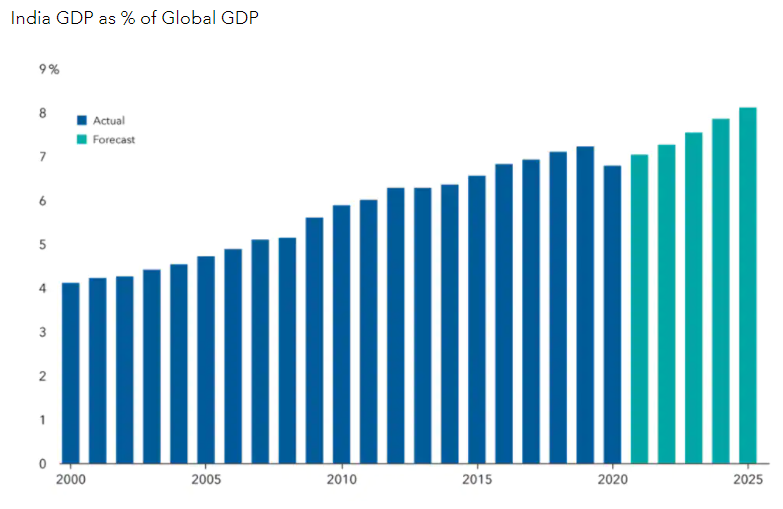

The nascent recovery, coupled with low interest rates, could start a virtuous cycle for the Indian economy. We believe GDP could reach double-digit growth in the 2022 fiscal year and could stabilise in the 6% to 8% range in later years.

A rising economic power

Key areas to watch

Some key sectors will be critical to watch for signs of progress — and investment opportunities — as India’s economy continues to mend.

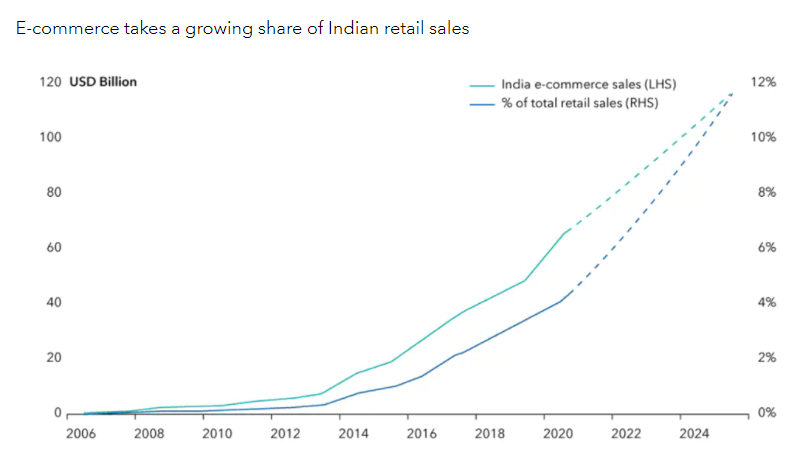

E-commerce: A hotly contested battleground. India’s digital transformation is moving at a brisk pace, pitting domestic technology companies against multinationals looking for a piece of the country’s large and youthful consumer market. Reliance Industries is at the centre of the fray. Its Jio mobile service launched in 2016 and recently surpassed 400 million subscribers. Growing from its roots as India’s largest oil and gas company, Reliance has transformed into a domestic technology powerhouse. But rather than go it alone, the company has teamed up with global multinationals looking for a gateway into India. Its broader vision is to connect manufacturers, retailers and consumers on the Jio platform. That’s what drove its strategic partnership with Facebook. Jio is also collaborating with Google to develop a low-priced Android smartphone.

Room to run

India’s banking system: A tale of two worlds. India’s banks have strong growth potential owing to relatively low market penetration and the rapid growth of mobile banking. But there is a sharp split between public and private banks. State-owned banks carry some of the highest ratios of bad loans in the world, a problem that the pandemic is likely to make worse. While a new bankruptcy law forced banks to recognise bad loans more quickly, it will take further reforms to get more credit flowing to stimulate growth and innovation. To that end, the government recently announced plans to create a “bad bank” to manage distressed loans.

In contrast, the larger private banks have been growing profits and gaining market share. They are well-positioned to scoop up some of the country’s weaker lenders.

Residential real estate: Less fragmented. In recent years, new laws have both formalised and legitimised the industry, leaving a few large, organised regional homebuilders including Godrej Properties, Sobha Ltd., and Brigade Enterprises as survivors. A speedy economic recovery in India could drive new demand for homes in urban areas. Besides the homebuilders themselves, opportunities could arise for companies that provide cement, paint, tiles or household appliances.

Consumer market: Dominated by multinationals. India’s consumer market has been dominated by subsidiaries of multinationals such as Hindustan Lever, a unit of Unilever. Pepsi, Nestlé, Mondelez and Coca-Cola are pursuing greater market share through a host of innovative strategies targeted at hypermarkets. This is a high-growth area that will likely see the emergence of new domestic players and the entry of a larger group of multinationals.

Further progress on reforms will be key

To realise its full potential and keep markets humming, India will have to implement deep-seated structural reforms. Since taking power in 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has implemented a series of reforms aimed at modernising the economy, increasing the ease of doing business, rooting out corruption and raising living standards. His government has seen the pandemic as an opportunity to push long-pending measures affecting agriculture, labour and domestic manufacturing. However, major reforms can be challenging, as we’ve recently seen with widespread protests by farmers over new agricultural laws.

In our experience, we have found the quality of management of India’s private-sector companies to be on par with the best in the world. Should structural reforms unleash a higher domestic growth rate, many of these companies would be well-positioned to grow both top line and bottom line at a faster pace than many of their global and emerging markets peers. At a market capitalisation of about $872 billion, based on the MSCI India Investible Market Index (IMI) as at 31 December 2020, India’s equity market is still relatively small compared with the size of the economy and its potential growth. That could mean an expanding opportunity set in India over the coming years.