In 1996, the British economist Roger Bootle headlined that “The death of inflation” had come. Today, more than two decades later, he sees signs of its resurrection1. With this opinion he is not alone. The fear that inflation is coming back seems pervasive.

There is no clear view from the inflation discussion: While some see the rise in inflation as temporary, others fear that rising prices could manifest permanently. The latter opinion is currently supported by the latest inflation figures, which rose sharply in the majority of Western countries over the past twelve months: In the US, for example, to 5.4% – the highest value in 13 years.

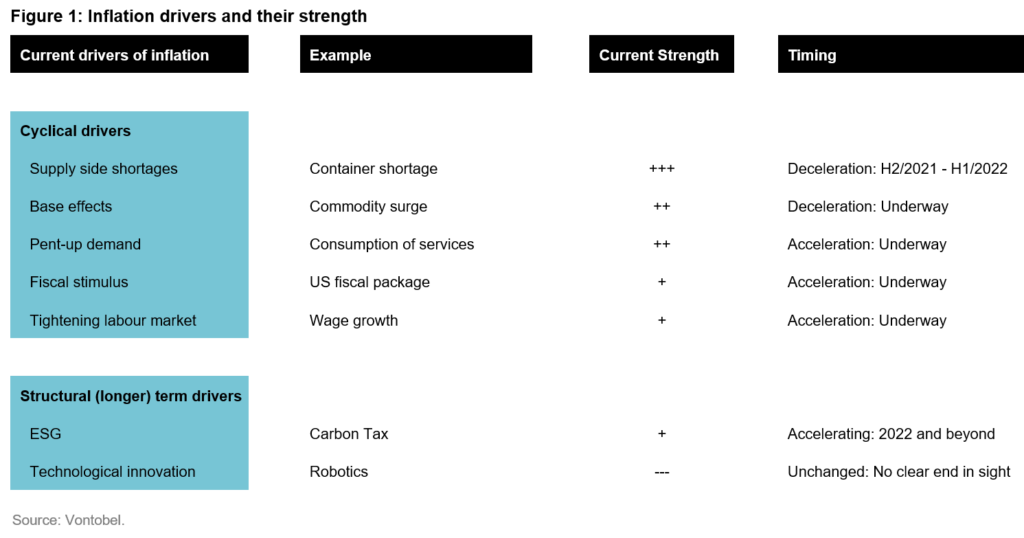

These recent sharp rises in inflation rates are attributable to various short- and long-term factors, which can be either temporary or permanent in nature (see figure 1). To assess long-term price developments, we analyze these factors and also identify deflationary drivers. This analysis is of particular interest to investors, as the future inflation environment has a direct impact on equity and bond markets.

Arguments for temporary inflation

Many factors currently argue that inflation is temporary. Besides base effects, supply chain challenges, rising microchip and commodity prices, this also concerns full employment and the liquidity flow of central bank money.

Base effects

The base effect measures inflation as an annual rate of change. It thus depends on the past as well. In the current situation, this means that the current high inflation is less due to today’s high price level than to last year’s relatively low-price level. The usual calculation of annual inflation does not take into account the influence of the pandemic on price development – in May 2020, 14 EU countries recorded a negative inflation rate.

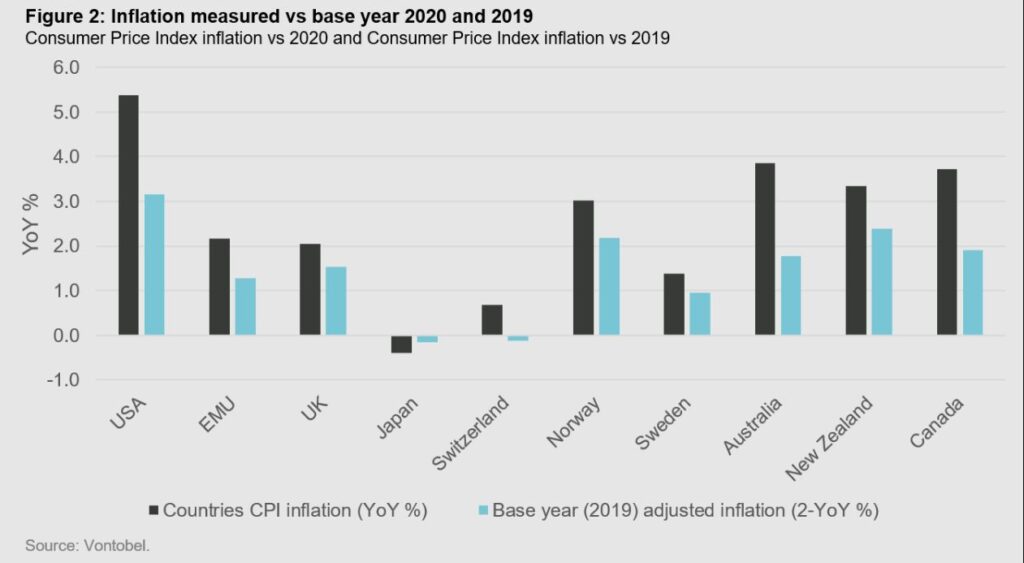

If, instead of the previous year’s comparison, July 2019 is used as the base month, a simple analysis of 40 countries shows that inflation is significantly lower in 36 countries (see figure 2). According to this calculation, it only amounts to 3.2 % in the USA and 1.5 % in the UK. Thus, the contribution of base effects to inflationary measures should fade as we measure price changes versus a more “normal” year.

Supply chain challenges

Another reason for the current inflationary pressure is a shipping container shortage that threatens global trade. Due to the COVID restrictions, shipping companies’ delivery speed and thus the supply of containers has been greatly reduced. The consequences of this shortage can be observed worldwide, as many items cannot be shipped as usual. This creates an inflation multiplier: significant increases in transport costs are passed on to consumers, whilst product scarcity drives prices even higher. Our view is that once the pandemic is over, container supply and transportation should return to normal, so this inflation driver should be temporary.

Microchip prices

A supply shortage can also be observed for microchips. The pandemic has led to a significant increase in demand for electrical goods, for example home office products. Problematic in this context is that supply bottlenecks in the semiconductor segment can only be corrected slowly, as it takes time and money to build up production capacities. However, both the USA and Europe, as well as some chip manufacturers, have signaled their intention to build up production capacities, which suggests a normalization in the coming year at the latest. DRAM spot prices, for instance, already peaked mid-July.

Commodity prices

Increased commodity prices also play a significant role in the inflationary push. This is mainly due to the increase in the price of oil by more than 150% in spring this year compared to the previous year. This price rise, which is responsible for more than one third of the current inflation, has led to strong inflationary pressure on energy-sensitive consumer prices. However, there are increasing signs that oil prices are stabilizing – the annual growth rate already declined to 50% since spring – suggesting that the oil price effect will dissipate over time.

No full employment

Economic thinking today is still shaped by the basic belief of the Phillips curve2. According to this, the lower the unemployment rate the higher the wage growth and therefore the inflation potential of an economy. Information on these inflation dynamics is provided by our business cycle model “Wave”, which allows us to calculate the current stage of the business cycle based on data from more than 50 countries. The Wave model processes more than 150 labor market statistics, which currently signal that there is almost no full employment in any country, which would create inflation risks through wage pressure.

It is true that some countries, in particular the US, have seen wage pressure in certain service sector segments of the labor market as people did not want to re-enter the labor force post-COVID. However, as COVID support measures will be scaled back over time, we do expect these employees to re-enter the labor force at some point.

Liquidity flow of central bank money

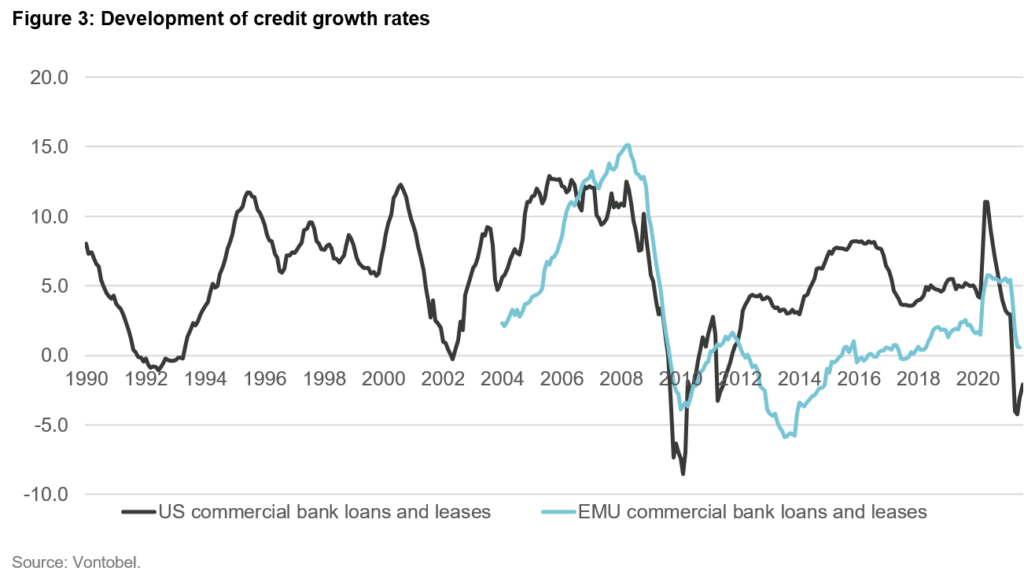

Inflation is also influenced by the loose monetary policy that has been in place in all global regions since March 2020. The aim of this global expansionary monetary policy is to mitigate the consequences of the pandemic and to stimulate economic activity. One indicator of whether these monetary policy decisions are having the intended effect on the real economy is the development of credit growth rates. They indicate whether the additional liquidity coming into the system is flowing into the goods or the financial markets.

The current weak credit growth rates in many countries show that the majority of the increase in the money supply is not discharged into the real economy (see figure 3), but rather into the financial markets, where it leads to asset price inflation, which can be seen in the steadily rising real estate prices and equity prices.

Arguments for permanent inflation

Although there is much to be argued for transitory inflationary pressures, there are good reasons to believe that inflation will not fall back to 2019 levels this year or next. Besides demand picking up against a (not yet fully employed) services sector, it is also the gigantic fiscal stimulus as well as the ESG trend that could permanently push up inflation.

Rising demand meets a (not yet fully employed) service sector

A common cause of inflation is a strong increase in demand meeting (temporary) supply constraints. Currently, we are facing such a situation. Due to the measures of the Corona lockdowns, the ability to spend money has been limited. This has led to higher savings rates in large parts of the world. The opening of the economy is now triggering a release of saving in certain sectors, with consumers currently particularly looking to spend their money on experiences and leisure.

This affects especially the hospitality industry: businesses that have been closed for a long time are encountering a rush of demand after the reopening that they can hardly cope with. This is clearly evident in the US, where the service sector workforce has not yet been restocked to 2019 levels. As a result, labor shortages are leading to rising wages in the low-wage segment, as labor demand is currently greater than supply.

However, the extent to which pent-up consumption demand will drive inflation, especially in the services sector, is difficult to assess at present. One hint that the pent-up demand is not coming back as strongly as expected is, that saving rates – as of today – do not drop as quickly as expected. It seems it will take a bit longer until consumption normalizes.

Gigantic fiscal stimulus supports demand

The global fiscal policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, which were designed to help counteract the economic effects of the crisis, are also having an impact on inflation. Around the globe, policymakers have adopted various measures to help stabilize the economy at large. The gigantic fiscal packages that were stoked in the process were intended to prevent a collapse in capacity utilization and aggregate demand. This extensive government spending is likely to have a longer-lasting effect on consumer prices. As of today, however, we do not observe a broad-based price effect of fiscal packages.

ESG as an inflation driver

The ESG trend may also prove to be an inflation driver in the medium to longer term . Regarding climate and environmental protection, the planned or already introduced CO2 prices will lead to an increase in energy prices – both for consumers and for companies. The latter will subsequently also be confronted with higher supply costs, which in turn could be passed on to consumers in the form of price increases. The sustainability issue, though, also concerns measures for fairer wages, better working conditions and more equality, which are guaranteed to lead to higher prices. The only uncertainty it seems is when this price effect will materialize and not if.

Structural deflationary drivers

In addition to transitory factors, there are also several structural factors that have a deflationary character. These deflationary forces, which include reduction of unit costs in digital goods as well as new forms of work, are expected to have a downward effect on inflation.

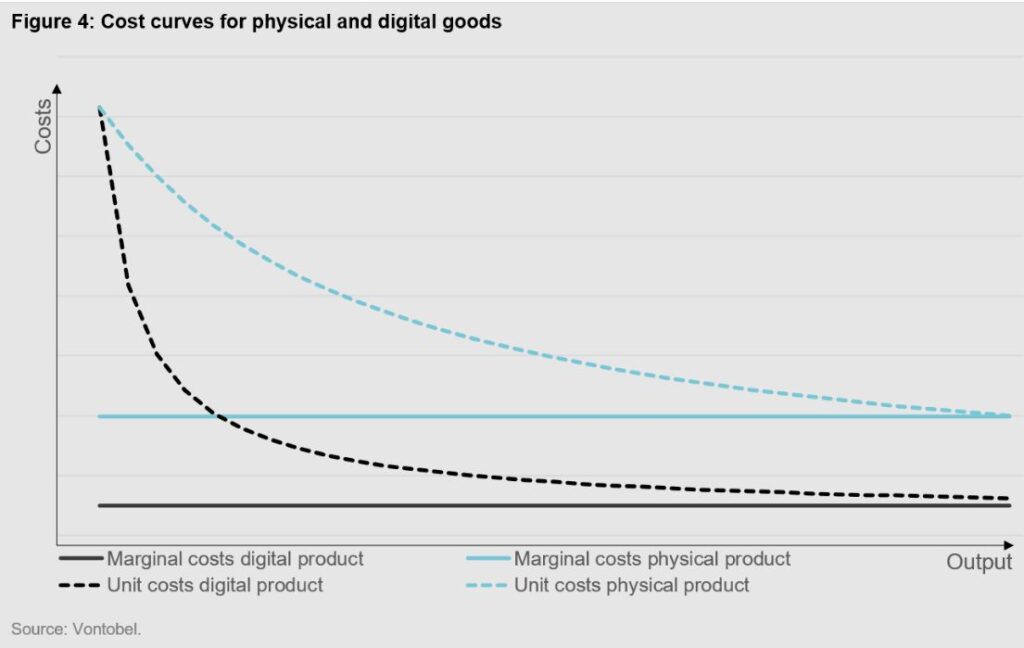

Unit cost degression for digital goods

In many cases, digital goods are not only cheaper than their analog counterparts – they usually also have a different cost structure. A common characteristic is the economies of scale effect. This results from the fact that the development of digital goods is characterized by a high fixed cost share, which is usually offset by low variable costs. The lower the variable costs in relation to the fixed costs, the more the unit costs fall as the sales volume increases (see figure 4).

A good example of this is a music track. The production costs are relatively high (studio, singer, band, etc.), but nowadays there is no need to produce a sound carrier or pay a distributor. Audio content can be downloaded by users from the Internet without any additional cost to the producer. Conversely, this means that the marginal cost of selling an additional song converges to zero. Digital goods therefore have very low marginal costs and thus push down the price level as pricing tends towards the marginal cost.

Many digital goods do not have a monetary price anyway, for example, in social networks where people pay using their personal data rather than money. However, new technologies – such as 3D printing, virtual reality, or robotics – and the spread of the sharing economy, which is causing a decline in demand for goods that are captured in GDP statistics, also have deflationary effects.

New work

Structural trends and the associated new forms of work, which have been boosted by the Corona crisis, are also having a dampening effect on inflation. The fact that many employees are currently working at home and will continue to do so in the future means that monthly household expenses are falling more sharply than incomes, because lunch, for example, is prepared comparatively cheaply at home.

Transitory or permanent inflation?

Is inflation dead or are we witnessing its resurrection? In our view, inflation will remain static or even rise in some countries in the coming months due to the temporary factors highlighted. After that, the pace will most likely slow down again as base effects and supply side shortages fade.

Market-related data, such as inflation expectations, which have been declining since mid-May, support the view that inflation has reached its peak. Many pandemic-related effects that are currently driving inflation will come to an end next year at the latest.

The longer-term inflation trend is more difficult to predict. Technological progress should remain a drag on inflation and may remain the major driving force leading to sustainably low inflation pressure. The fiscal boost and the implementation of ESG measures, however, suggest that inflation will not fall back to pre-COVID levels anytime soon.

What does this mean for investors?

So called real asset, such as gold, commodities, real estate, but also equities relative to bonds, have proven their function as inflation hedges over time and should remain a good hedge against inflation surprises and the outlined risks. However, our view of rather transitory inflation pressure and inflation peaking later this year suggest that returns on these real assets should be lower than previously. Lower returns in the commodity and equity space are, however, not only because of peak inflation but because peak growth is the most likely scenario going forward.3 As these two assets are more sensitive to real GDP growth, the leading indicator of fading economic momentum, captured by our “Wave” model, limits our return expectations for both asset classes. But it is worth noting, that as long growth momentum slowly fades, returns are likely to stay positive for the time being for these asset classes. This is currently in particular the case for Developed Market equities.

1. Interview with Bloomberg 07.06.2021.

2. Phillips, A. W. (1958). The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom 1861–1957. Economica, New Series, 25 (100), pp. 283-299.

3. The term “peak growth” originates from the business cycle literature. According to this, an economy oscillates between its growth peak and its trough. The latter often coincides with an economic recession, while the former describes the point in the business cycle at which economic growth rates have peaked and from which on economic growth slows down.