Changing workforce demographics, Covid and climate change are pushing prices higher, leading to investment strategy shifts. Steven Hay, co-manager of the Multi Asset Income fund explains the forces at play.

“Inflation is when you pay $15 for the $10 haircut you used to get for $5 when you had hair.”

For a while, it seemed like high inflation in developed markets had been confined to the history books.

For years we wondered if prices would even rise fast enough again to meet central bank expectations. But now above-target inflation is back in the headlines, and there’s growing concern it may stay that way for a long time to come.

There’s good reason to worry: inflation is a significant risk to investment returns. For anyone relying on a fixed income, one or two years of higher inflation is a bit painful, but a prolonged spell can profoundly dent their purchasing power. For a long-term income to be sustainable, it needs to be inflation-proof.

The Multi Asset Income Fund aims to deliver a resilient monthly income, while preserving the real value of income and capital – ie adjusting for price-level changes – so inflation risk is very much front and centre in our minds. We believe that the risk of a prolonged period of higher inflation is now much higher than at any point in more than 30 years.

All the time, we balance the need for high income today with investments that might not be the highest yielders right now but have the potential to deliver growing income over time. This should help ensure we meet our objectives and is the thing that many income investors ignore because they are too short term.

As we say, we invest for long-term income, not short-term yield. The higher risk of inflation brings the long-term outlook into an even sharper focus. And it makes us think harder about selecting investments that can provide enough income growth to keep pace with a rising cost of living.

Having nine different asset classes to choose from gives us a great degree of flexibility to move the fund towards asset classes that are likely to perform better in a world of fast price gains.

And as you would expect from Baillie Gifford, we have a real focus on investing in the right companies. For each investment case, we consider how the business would do in an inflationary scenario, for example, whether it has pricing power.

I have more to say on our strategy. But first I want to provide some context.

Before joining Baillie Gifford, I worked at the Bank of England, providing research to the Monetary Policy Committee, so I have some insight into how central bankers view the current dynamic.

And I’d like to explore both what’s causing prices to rise and how interest rate setters might react.

Fiscal stimulus

While anecdotes are no substitute for hard data, we are all aware of mounting inflationary pressure.

There are shortages of the ‘right type’ of workers in hospitality and logistics as well as the professional services. There will apparently be toy and turkey shortages at Christmas. What is going on?

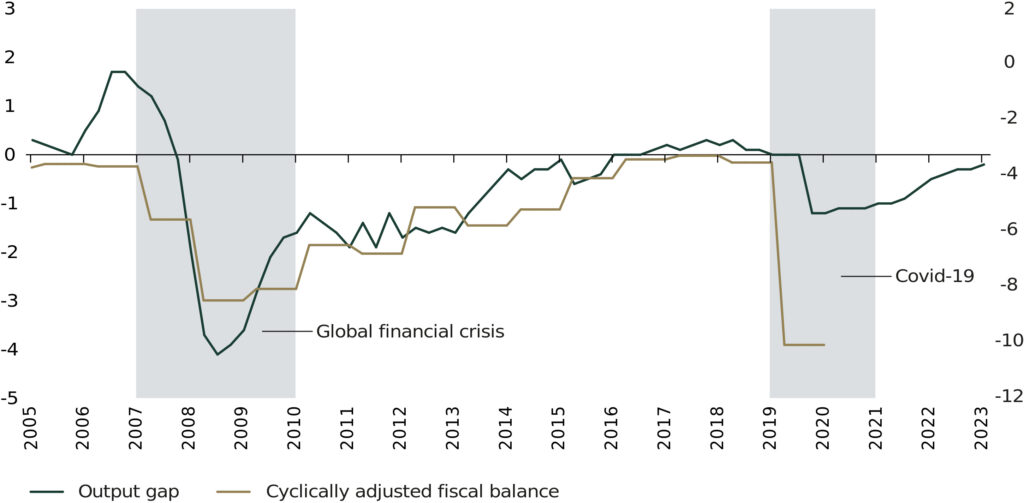

In a typical recession, economic activity gets hit and a large rift opens between actual economic performance and what’s regarded to be its potential. Economists call this the output gap. Usually, government spending comes to the rescue and plugs the gap. This causes the fiscal deficit – the difference between government income and outgoings – to grow.

The UK output gap and fiscal stimulus

The pandemic presented a very different type of recession. Because of the many restrictions on activity, economic potential was hit almost as much as economic demand. Consequently, only a very small gap opened between actual growth and potential growth. Yet, more fiscal stimulus has been provided than in the global financial crisis of 2007–08.

We also need to remember there has also been a huge amount of monetary stimulus through quantitative easing. The Bank of England has printed £440bn extra money, amounting to nearly 25 per cent of GDP, and injected it into the economy. The extra liquidity is bidding up asset prices and will find its way into the price of everything.

If supply cannot expand to meet all this higher demand, we will get higher inflation.

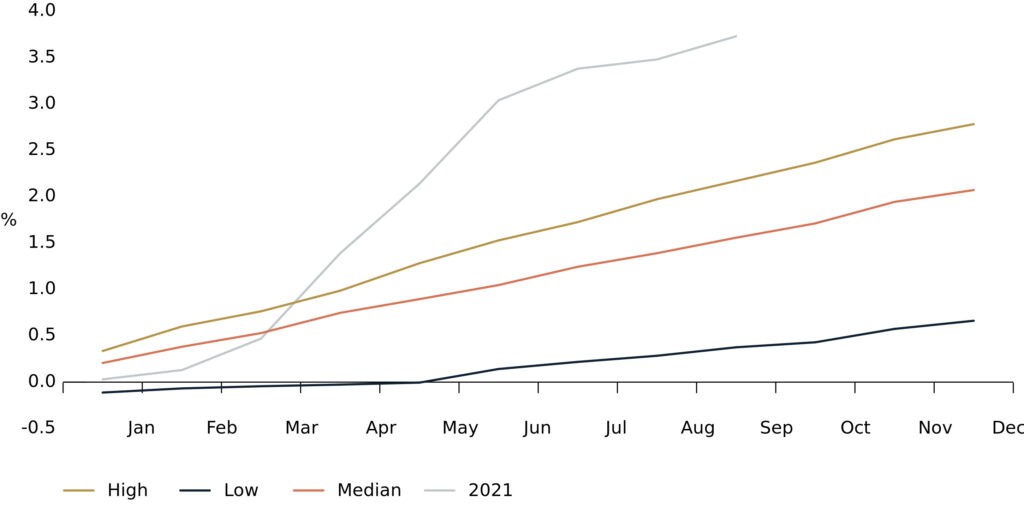

The situation is even more extreme in the US, where the path of inflation is off the scale compared with the last two decades.

Core US price rises over course of a single year

The above graph shows accumulated price rises in consumer goods and services (but not food and energy) over the course of a year, illustrating how fast prices have been rising in the US this year compared to the experience of the past 20 years.

Taken together, the current cyclical inflationary dynamic is the strongest I can remember for many years and it is likely to light the fuse on rising inflation expectations.

Pay rises

In thinking about inflation’s long-term path, we need to look at structural shifts in the economy. We won’t get a sustained period of general inflation without wages growing. Otherwise prices would have to fall back after any rise as we would have only a limited ability to use savings to boost spending above our incomes.

Over recent decades, there has been a lot of downward pressure on wages from big structural forces such as globalisation, automation and demographics. But the key question is what happens next.

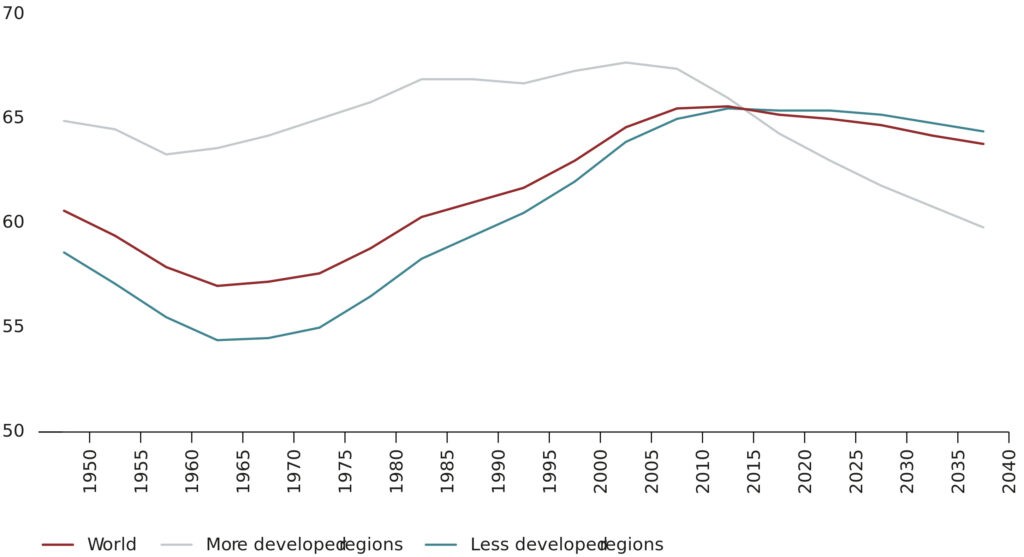

The percentage of the world’s population made up of those aged between 15 and 64 and willing to work (the working age population) has been falling for a while. Yet this has not translated into higher real wages. A key reason was globalisation. Manufacturing moved to lower-income countries with young, growing populations. The UK could access cheaper imports from first Japan, then Korea and Taiwan, and then China. Meanwhile companies outsourced services to the likes of India and the Philippines.

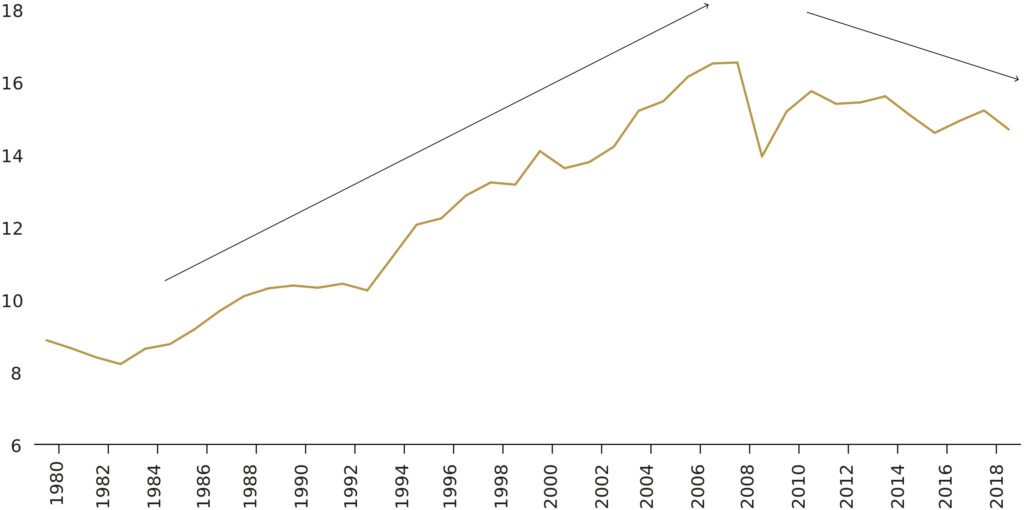

But there are grounds to believe that globalisation’s impact has peaked.

Globalisation is a hard concept to measure, but one way is to use global trade as a proxy. For many years, global trade accounted for a growing share of GDP. But this trend has stalled and maybe even gone into reverse.

Global merchandise exports as % GDP

One reason is that the one-off integration of countries like China and the ex-Soviet bloc into the global trading system has now happened and is not being repeated. It’s also the case that the political landscape has become less conducive to shifting production overseas. Tensions between the US and China, for example, are making CEOs think twice about relocating manufacturing. Another more recent trend is that the pandemic and climate change have pressured companies to source locally and keep their supply chains short.

In addition, global demographics are starting to resemble those of the developed world. Birth rates everywhere are falling, and the percentage of people within the world’s working age population is shrinking. While this might be mitigated by people working for longer, there’s a limit to how long people can stay in the labour force.

Working age population as a share of total population

Ultimately, we are coming from a deflationary period of increasing access to a growing global workforce, to a new reality where local labour market conditions matter more. If there’s a shortage of workers, then rather than outsource to an emerging market or bring in immigrant labour the only option may be to pay them more. And this will lead to inflation.

There’s a suggestion that automation might prevent workers’ bargaining power from improving even though they might be becoming scarcer. Automation does of course have huge potential to replace labour and in the very long run it’s likely machines will be able to do most jobs. But while AI is making huge strides, I think the speed at which it can replace people is overestimated. It is not a significant enough force to keep the lid on inflation.

Central bank concerns

One could argue that while it is interesting to debate structural shifts, inflation’s path will ultimately be controlled by central banks: they have the toolkit and the know-how to manage an inflation spike and bring price rises back to their target.

But while the central banks will taper their asset purchases, they will find it difficult to fully lean against inflation. Tightening is easy when the economy is growing quickly. But they will find themselves in a tricky situation if inflation is too high and at the same time growth is faltering and financial markets falling.

Central bankers have not been in that position since the 1980s. And there’s two reasons they won’t find it that easy to tighten: the loss of fiscal discipline and society’s attitudes to inflation.

Governments have shown themselves willing to throw fiscal discipline out the window. Even after we move beyond Covid-19, climate change will require state investments in essential infrastructure to fight climate change. Global warming poses an existential threat that demands government action and justifies large-scale fiscal spending. If the result is higher inflation, central banks would be placed in the unenviable position of having to raise interest rates and stop buying government debt through quantitative easing programmes. And that would add to the already gargantuan cost of critical government programmes.

The UK’s debt is now so high that, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility, raising interest rates 1 per cent would add £21bn to the Treasury’s interest bill. That’s a lot of hospitals or grants for hydrogen boilers. Whereas a bit of inflation does wonders in eroding the real value of the government’s debt.

On top of this, the bigger question is whether society is anti-inflation anymore. Ultimately it is what society wants that determines inflation – remember that it is the government that sets the central bank’s objective.

Mechanically we know how to control inflation. The question is whether we are willing to take the pain required to do so. After the high inflation of the 1970s and 80s, there was a clear mandate from society to bring down inflation. I believe that has significantly weakened and people care more about the climate and inequality than they do about whether inflation is 2 per cent or 4 per cent.

So if central banks make excuses for why inflation is temporary and don’t respond, then inflation expectations will rise. And the longer they stay high the more entrenched they will become.

That could lead to a much longer period of higher inflation until central banks are eventually forced to respond more aggressively.

Protecting income

As mentioned at the start, the Multi Asset Income Fund aims to grow income and capital at least in line with inflation.

And we are leaning both on asset allocation and stock selection to prepare the portfolio for the risk of higher inflation.

The areas that are most negatively affected are government bonds and high-grade corporate bonds. These are nominal assets where you are not compensated for higher inflation. We have almost completely sold out of these asset classes.

Within fixed income, we prefer high-yield bonds and emerging market debt. High-yield bonds are relatively more attractive because their shorter terms make them less sensitive to inflation, but also because inflation erodes the real value of debt, which is especially helpful to companies with lower credit quality. And in emerging markets we are typically seeing weaker inflationary dynamics, so again having a global approach helps.

Instead, we have been adding to real assets – the term given to tangible things with inherent physical worth. This includes investments in infrastructure and property, where the cash flows are often directly or indirectly linked to inflation. Equities also offer protection against inflation, and we have been adding to holdings in gold miners. We think they will do particularly well in an inflationary scenario.

It is important to bear in mind that for every asset class, we invest in a bespoke income-oriented portfolio run by our colleagues at Baillie Gifford. That’s because we believe security selection is crucial to creating a long-term, resilient income.

In the inflationary world, we are paying particular attention to the ability of companies to pass on price rises. Take the example from our equity portfolio of Watsco, a distributor of energy efficient air conditioning units. It passes any price increases straight on to consumers and takes the same margin on a higher dollar volume, so periods of inflation have historically been very favourable to it.

While property as an asset class has a mixed record of protecting against inflation, residential property has attractive characteristics. Rental income is supported by employment income. So if wages are growing, rents can follow. Irish Residential Properties (IRES), an Irish residential-focused real estate investment trust, exemplifies this. It has supportive fundamentals with a strong urbanisation trend and barriers to new supply. These make its income growth prospects attractive.

In infrastructure too we have found investments that can protect against inflation. HICL Infrastructure has revenues from public-private partnership projects that are inflation-linked and from the public sector. These make it an ideal investment for the fund because it is resilient to both the economic cycle and inflation.

While we see the risks of higher inflation as material we don’t have all our eggs in the high inflation basket. Our portfolio should enable us to achieve the fund’s objectives even if inflation is subdued. It’s just that we have more of an eye than most on the risks from higher inflation.