Many countries in the developed world are experiencing a shortage of workers even though economic growth is expected to be low or even negative. This shortage can be attributed to the many different, and still widely misunderstood, consequences of the pandemic, along with the ageing population and the new inflationary environment.

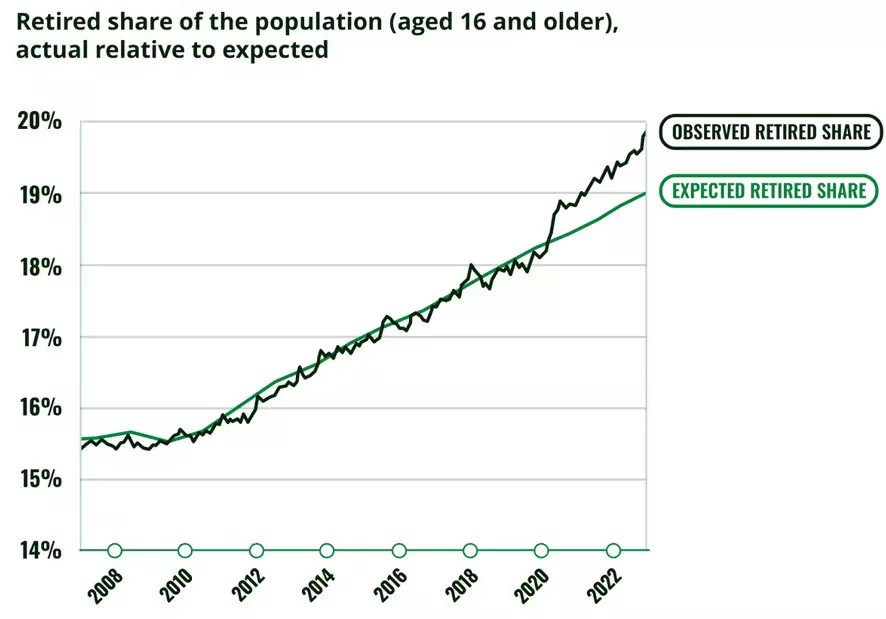

As shown in the above graph from the US Federal Reserve, the pandemic has prompted large numbers of people to take early retirement – a lifestyle change made possible thanks to excess savings built up as a result of the government’s stimulus measures and a forced two-year hiatus on consumer spending. These early pensioners are one factor behind the marked decrease in the US labour-force participation rate; other factors include a decline in the number of two-income households and an increase in part-time working, both of which reflect changing aspirations: work is less important to people now than it used to be.

The pandemic also caused working from home to become more widespread. We don’t know what effects this will have on long-term productivity once the initial enthusiasm dies down. If it leads to a drop in productivity, then more employees will be needed, especially given that so many are apparently unable to work as a result of long Covid.

In addition to this sociological factor, the pandemic significantly curtailed immigration. How can governments best shape immigration policy in response to the reshoring of strategic industries, at a time when the ageing population is reducing the pool of available workers? And given that the population is ageing, how long should working life last? What we saw in Japan, where an increasingly elderly population came hand-in-hand with full employment and anaemic economic growth, should serve as a wake-up call.

Alongside the evaporating workforce, employment rates are already quite high despite a rather weak economic growth. When inflation occurs during slowdowns or even recessions, the job market tends to remain tight for quite a while. That’s because higher prices drive up corporate revenue and mask the decline in sales volumes, a quimaking managers slow to enact cost-cutting measures such as redundancies. Job market adjustments in inflationary recessions are usually belated and brutal.

Consumers will inevitably soon struggle to pay their bills and GDP growth will start to fall, causing the job market to return to normal – but only in part. These factors won’t erase the consequences of new worker aspirations or the ageing population. The shortage of workers will be a structural phenomenon.