As we enter the third year of the pandemic, most market participants are asking themselves (once again) if this will be the year when supply chain issues finally abate. Despite the short term chaos that Omicron is causing in certain businesses such as airlines and travel, most people seem to think that 2022 will bring about some tangible progress in this regard. In our view, it is interesting to look at the often overlooked Inventories data to assess to what extent a normalisation might be underway.

Inventories, or more precisely changes in inventories, are a part of GDP. Suppose in a given period a country produces more goods and services than those demanded internally and by trading partners (on a net basis). In that case, this country accumulates inventories, which means GDP growth is higher than what it would have been otherwise. The opposite happens if demand outpaces production. In this case, the country draws on its Inventories, which is a “drag” on growth. Typically what happens in a recession is that production is cut. companies run higher spare capacity, produce less than optimally and draw on their inventories to meet subdued demand levels. As a result, economic growth is worse than pure demand indicators suggest. However, when there are signs of light at the end of the tunnel, production increases again as companies produce more to meet increasing demand and to bring their inventories back to more normalised levels.

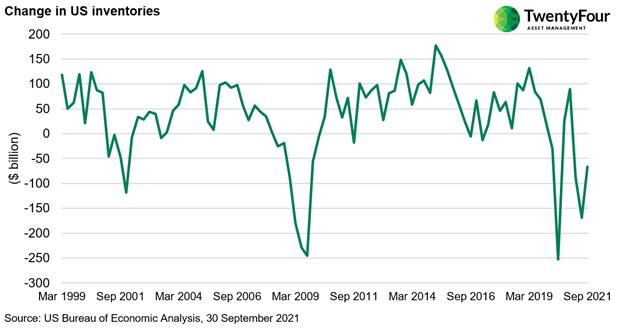

One of the countless peculiarities of this cycle is that the aforementioned did not happen. When the light at the end of the tunnel appeared, companies could not produce enough to satisfy demand and build inventories back to pre-COVID levels. Consequently, if we take the U.S. as an example in the graph below, we can see that inventories continue to drag on GDP growth despite the recession ceasing a few quarters ago. In other words, we have witnessed a robust recovery even though inventories have been subtracting from growth in most quarters since the pandemic started. The change in inventory levels is likely to be a powerful force if and when supply chains normalise, and it does look like this might happen in 2022.

The ISM Manufacturing data gives us more timely information than GDP, and earlier this week we received the December figures for the U.S. Although shortages continue to constrain production, there are some encouraging signs. From the report: “Inputs — expressed as supplier deliveries, inventories, and imports — continued to constrain production expansion, but there are clear signs of improved delivery performance. The Supplier Deliveries Index again slowed while the Inventories Index expanded, both at a slower rate”. So, although the headline number disappointed compared to expectations, the sector’s prospects overall continue to be positive.

In conclusion, growth in 2022 might benefit from a build-up in inventories, and we believe market participants are somewhat overlooking this. This fact adds to our positive view of the macro environment for 2022. A global economy growing above potential (although at a slower pace than in 2020) and monetary policy normalisation is a reasonable environment for taking credit risk while avoiding interest rate risk in fixed income.