Key points

- We expect pressure on global supply to gradually decline, contributing to a slowdown in inflation

- This would allow central banks to maintain a prudent approach to the pace of policy normalization

- It has become impossible to think about the macro outlook without considering the impact of the fight against climate change. Over 2022-2023,

Receding pressure on supply

2020 was a year of massive compression of economic activity. 2021 was a year of fast decompression, with demand catching up quickly as we were reopening, exerting significant pressure on supply, triggering a rise in consumer prices unseen in decades. Under the assumption – of course uncertain as we write those lines – that the Omicron variant does not trigger a generalised return to far-reaching sanitary restrictions, we believe 2022 will be a year of gradual absorption of the pandemic shock, with robust but less spectacular GDP numbers, as much of the catch-up is now behind us, and a normalisation of supply conditions allowing inflation to slow down.

Lingering sanitary-related supply-side disruptions played a large role in the emergence of global bottlenecks but demand also played a major role. Everywhere, individuals shifted their consumption from services towards tradable goods, which often depend on long and tortuous international value chains. This has been particularly acute in the US. There, as of the third quarter of 2021 (Q3 2021), household spending on goods had risen by 15% relative to its pre-pandemic level, the steepest gain since data has been available in 1947. Given the US dominance in world consumption – 30% in nominal terms in 2019 – this “goods glut” had a massive impact on global supply. Assuming the pandemic no longer forces widespread compression in services activity, this phenomenon should be behind us by now. Consumption of goods in the US has receded – finally – in Q3 2021.

Some key international prices are already abating – e.g., iron ore, of the cost of sea freight – and talks of releasing strategic reserves seem to have finally capped oil prices. The capacity of this improvement in upstream inflationary pressure to dampen consumer prices will depend on the result of a “race” with second-round effects transiting via the labour market.

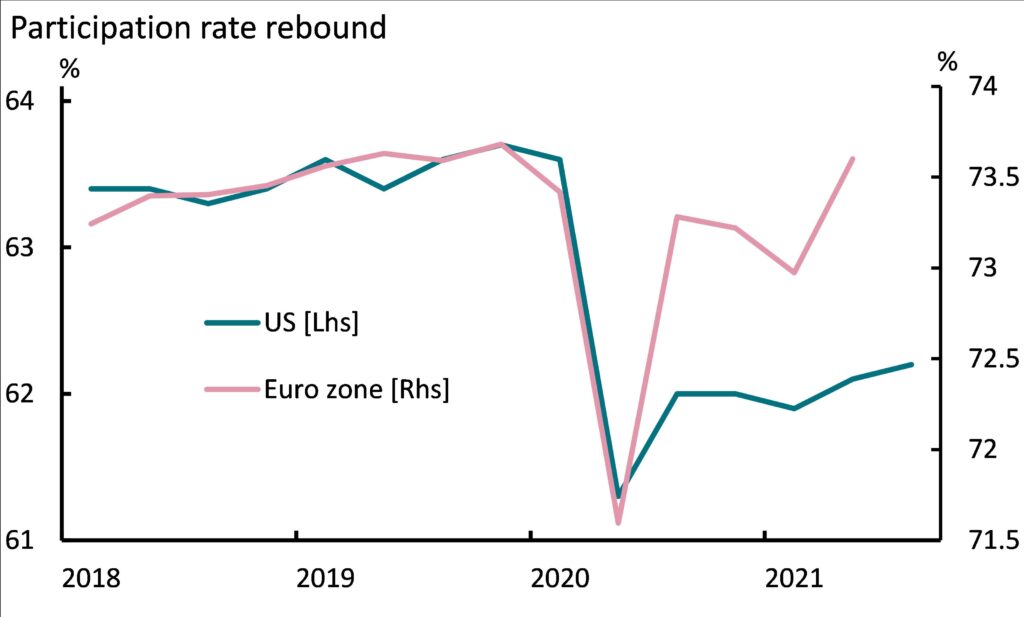

A normalisation of the US participation rate, easing the pressure on wages, is a key assumption in our baseline. Indeed, we think that a significant share of the persistent decline reflects lingering COVID-related issues – in particular around childcare. In Europe, the rebound in hiring difficulties is still to a large extent a return to structural flaws, most often skills mismatches, but contrary to the US no sign of wage acceleration can be observed (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: No drop in participation in Europe

Add Your Heading Text Here

In the advanced economies, economic policies will remain accommodative. True, the new fiscal packages, especially in the US, are much smaller than in the last two years. But much of the past fiscal push has been “stored” in the form of excess savings by households, creating a welcome reserve of demand.

While central banks are starting to phase down their stimulus, our baseline is that they will remain prudent, in line with our scenario of gradual convergence of inflation towards their target after still elevated year-on-year prints in the first half of 2022 (1H 2022). The first hike would come only at the end of 2022 in the US, reflecting the Federal Reserve (Fed)’s commitment to tolerate some inflation over-shooting. With even less endogenous price pressure and less advanced in the cycle than the US, we think this will take even more time in the Euro area and we don’t expect the European Central Bank (ECB) to hike before 2023.

Regarding the ECB, focus is probably less on policy rates and more about the phasing out of quantitative easing. In our baseline, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) would be terminated in March 2022 but partly offset by a recalibration of asset purchase programme (APP) to EUR40bn per month until the end of 2022 “at least”.

In the emerging world though, the credibility of central banks is not as strong and has forced them to engage in a significant monetary tightening, dampening demand. In some of the countries which are for now bucking the trend – such as Turkey, where the central bank is cutting rates – the fallout is massive in terms of currency depreciation. Emerging Markets will also be facing the headwind of less supportive Chinese demand, to which they are more sensitive than most advanced economies.

Indeed, China for once is not playing the role of a “global engine of growth”. Instead, Beijing is trying to address years of excess in the real estate sector, and this will slow GDP growth, while its “zero case” Covid policy is potentially very costly to the recovery. While 5% is probably a “floor” to GDP growth – and we expect some policy loosening into 2022 – the world economy will have to deal with an unusually tepid Chinese demand.

In our baseline, while COVID remains an issue, with the continuation of regular “flare-ups” in one or another key economic regions of the world, we consider that the pattern established in 2020-2021, with each new pandemic wave being less damaging to economic activity than the previous one, would continue to be observed. In the European Union (EU) specifically, we think that the “Franco Italian” model of making access to key activities conditional on the vaccinal status will be adopted in more and more initially sceptical member states as a way to both protect the economy from far-reaching lockdowns and nudge hesitant citizens towards vaccination including boosters).

On the political front, the next two years will be active. In our baseline, in 2022 the current policy stance would not be materially affected by the electoral outcomes (no “upset” in the French presidential elections), but of course in the US the outcome of the midterm elections could be “policy paralysis” for two years if Republicans take back Congress, which is consistent with the polls at the time of writing. In 2023, elections in Spain and Italy will be on the watchlist, but we currently doubt speculation surrounding an early UK General Election.

Beyond COVID, risks around this baseline are probably balanced. Inflation could prove harder to curb in the advanced economies, which would force a much bigger policy tightening detrimental to demand. Symmetrically, a faster-than-expected normalisation of excess saving could deliver another bumper year for consumption.

The fight against climate change to boost growth (for now)

Finally, we think it has become impossible to elaborate a macroeconomic outlook without taking into account the impact of the fight against climate change.

COP26 has not delivered enough. The intermediate targets pledged by the governments for 2030 are still consistent with an average rise in temperature of 2.4 degrees by the end of the Century according to Climate Action Tracker. With the exception of the deal on methane, which will create new constraints for the oil & gas industry, and possibly the one on forests, none of the announcements in Glasgow have any tangible impact on corporate behaviour, and hence on economic activity. The most glaring hole is the failure to make progress towards carbon pricing at the global level. Indeed, investors and corporates need visibility on the future trajectory of carbon price.

Still, it would be wrong to consider that the fight against climate change is not already having an impact on the economy. It is often seen as a cost. But the notion of cost is ambiguous when it comes to decarbonising the world. An essential part of the process is to reallocate capital towards the sectors and businesses which are transitioning to a net

zero economy. This would result in some destruction of capital in the sectors and firms which did not adapt, but GDP cares only about gross investment. And the investment effort needed to get to net zero is going to be massive and is becoming tangible. Thanks to the Next Generation EU programme, of which 30% of the funds are dedicated to the green transition, coupled with national initiatives, we can expect an investment effort of between 2 and 6% of GDP in the key countries of the Euro area between now and 2026 towards the fight against climate change.

Now, looking ahead, some measures detrimental to GDP growth will also need to be taken down the line. It is going to be tempting to try to nudge reluctant emerging and developed countries towards making more efforts to decarbonize by imposing a carbon “border tax” on European Union (EU) imports. This will have a detrimental impact on purchasing power. The same applies to the extension of carbon pricing to more sectors in the EU. It will be impossible to avoid a detrimental effect on household purchasing power. Germany’ shift to renewables is often praised, but the development of these energies was paid for by a levy on households’ electricity bills which at its peak stood at a full 1% of disposable income. Yet, for our current forecasting horizon, the fight against climate change is likely to bring a positive contribution to GDP.