Key Takeaways

- A proposed new U.S. tax rule may raise withholding taxes on dividends for some foreign investors.

- This could shift foreign investment away from U.S. stocks, making it costlier for U.S. companies to raise money.

- We think the proposed rule is probably a negotiating tool to discourage other countries from raising taxes on U.S. companies.

- The rule may be softened, delayed, or never fully implemented by Congress.

It’s often said there are only two certainties in life: death and taxes. However, the tax landscape may become somewhat murkier, as the recently passed U.S. House budget bill may potentially lead to some non-U.S. investors paying more taxes than previously anticipated. Although policy uncertainty remains elevated, we think it’s worth discussing the potential impact of this tax measure, and why taking a disciplined approach remains the best course of action.

Tax Pro Quo

In May, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA)—the budget bill for this congressional cycle. Although the bill had more than 1,000 pages of text, there was an “899-ton” elephant in the room that caught the eye of many non-U.S. investors: a measure authorizing retaliatory taxes.

Section 899 of the OBBA aims to penalize foreign countries that put in place what the U.S. views as “unfair”, discriminatory taxes against U.S. corporations. The provision introduces gradually higher U.S. withholding taxes on dividends—and potentially other forms of passive income—to residents of these countries. This amounts to a “tax pro quo”: tax our companies, and we’ll tax your investors.

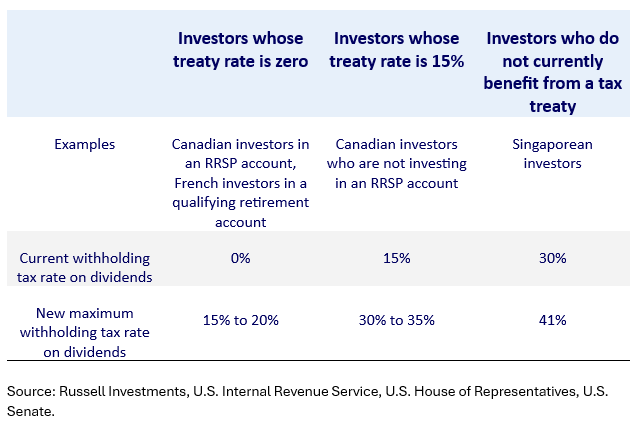

In the House version, withholding tax rates would rise by 5 percentage points annually, up to a maximum of 20 points above current levels. The total withholding tax rates are also capped at 41%. The Senate version would see a rate increase of up to 15 percentage points. These withholding tax increases would likely apply to dividend income, though may not apply to interest income from investing in U.S. treasuries or U.S. corporate bonds. The Senate version of the bill specifically codifies this exception.

In or Out?

As written, the bill gives the U.S. government a fair degree of flexibility in terms of defining what constitutes an “unfair” tax. However, there are some specific inclusions and exclusions.

- Specific Inclusion: Digital services taxes (DST) are specifically listed as a tax that would be subject to this provision. Canada, the UK and many of the countries in the European Union currently have a version of this tax, which means they could face these retaliatory taxes. In addition, any country that applies an Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR) tax would also be subject to this provision, putting countries like Australia on the list of potential targets too.

- Specific exclusion: Taxes on sales. For example, the Canadian Goods and Services Tax and the European Value Added Tax would not be deemed “unfair” taxes.

The broad reach of this rule means many of the U.S.’ closest trading partners and allies may be affected, creating uncertainty for a wide range of investors.

Dividend Downside

If Section 899 is enacted and a country is designated as discriminatory, the most direct consequence for its investors would be a reduction in after-tax returns on U.S. dividends. As the table below shows, withholding taxes could rise substantially. Note that for the third column, we assume the 41% cap on the total withholding tax rate contained in the House version holds.

However, the tax rate is only one part of the equation. We also need to consider the tax base. Relative to other markets, U.S. companies tend to pay lower dividends —for instance, the dividend yield on the S&P 500 Index was only 1.4% as of mid-June. Accordingly, a global equity investor holding a market cap-weighted portfolio and subject to an additional 15% U.S. dividend withholding tax (as per the Senate version) would only experience a return drag of roughly 0.13%.1 This is not ideal, but unlikely to alter the overall investment case for U.S. equity exposure in a diversified global portfolio.

Investors with a concentrated investment in higher dividend-yielding investments (like real estate investment trusts or utility companies) could see a bigger impact. These investors could potentially face a return drag of one full percentage point2, and may need to reassess the after-tax effectiveness of their investment strategy.

While we believe the exception for interest income would most likely hold in the final version of the bill, the potential withholding tax rate increases would create an even bigger return drag if the exemption is not maintained.

Beyond mechanical calculations of increased withholding taxes, the broader concern is behavioural. Section 899 may reinforce a growing worry among some foreign investors that the U.S. laws/regulations may be changing in a less predictable manner. Even if the direct tax effect appears modest, these perception concerns could alter the demand for U.S. assets.

This sentiment shift could prove more consequential over time. With U.S. stocks already expensive compared to historical averages and international peers, even a slight drop in demand from foreign investors could encourage more people to shift money into non-U.S. markets. Reallocation could be consequential, as non-U.S. investors account for nearly 20% of U.S. stock ownership3.

Down the line, this reallocation away from the U.S. could make it more expensive for U.S. companies to raise money—particularly in capital-intensive, high-dividend sectors. Over time, this may lead firms to scale back investment or expansion plans, potentially weighing on longer-term economic growth and dampening America’s competitive edge as a magnet for global capital.

Not the Final Word

Although Section 899 is often described by the media as a “revenge tax”, we believe that—similar to tariffs—this provision may be designed as a bargaining tool to discourage tax practices (like digital services taxes) that could raise tax bills for U.S. corporations.

In fact, the specific exclusion of sales taxes from the definition of unfair taxes may have been designed to help reach a compromise. That’s because it’s probably easier for Europe or Canada to repeal their digital services taxes rather than outright abolish their sales taxes. If the taxes covered by Section 899 are removed, investors won’t have to pay extra withholding taxes.

The final version of the budget bill could also be watered down further as lawmakers consider the potentially negative consequences of this rule.

Bargaining Chip

At face value, Section 899 should not be a major concern for most investors. The increase in withholding tax would likely be gradual and wouldn’t take effect before 2026-27. Even if fully implemented, the drag on returns is unlikely to be material for diversified portfolios unless interest income is also subject to withholdings. And given that members of the U.S. administration have expressed a desire to keep government borrowing costs low, we do not believe the government would subject interest income to these additional withholdings, as that could run counter to its objectives. The intent behind the measure appears less about retribution and more about leverage—a negotiating tool to pressure allies rather than a permanent shift in U.S. tax policy. In addition, there’s a real possibility the rule is softened, delayed, or never fully enacted.

But while the immediate financial impact may be limited, a longer-term and more subtle risk may be emerging. Section 899 contributes to a pattern of unilateral policymaking that increasingly blurs the line between economic strategy and diplomacy. And while we believe the U.S. is likely to retain its strategic advantage in technological innovation and new business formation, the competitive gap could gradually narrow over time should investors start rethinking their portfolio allocation.

In that sense, Section 899 may not be the heaviest burden. The true elephant in the room isn’t the provision itself, but what it signals about the future role of the U.S. in the global system. And that’s an elephant worth watching—however slowly it moves.

1 Assuming the U.S. stock market has a weight of 65% in global equities and a dividend yield of 1.4%

2 Illustrative scenario based on a 5% dividend yield

3 Source: Federal Reserve Z.1 (Q1 2025), U.S. Treasury

Any opinion expressed is that of Russell Investments, is not a statement of fact, is subject to change and does not constitute investment advice.