This year’s annual economic policy symposium in Jackson Hole opens the six months that will likely define the legacy of the Powell Fed’s first term. The robust recovery, high inflation and record asset prices call for the Fed to wind down an extraordinary monetary easing that is also exacerbating economic inequality. But leaving QE isn’t easy, as financial markets have become overly dependent on Fed support. In her latest “On My Mind,” our Fixed Income CIO Sonal Desai discusses the Fed’s challenges and what they mean for investors.

This year’s global symposium of central bankers, policymakers and academic economists in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, comes at a very important juncture for Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Jerome Powell. The Powell Fed has had a successful run so far, but it’s the next six months that will likely define the legacy of Powell’s current term as Fed chair. And the symposium’s focus on inequality—the official theme is “Economic Policy in an Uneven Economy”—further highlights how important the Fed’s challenge is.

The Fed’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak last year was impeccable: prompt, decisive, creative and well-designed. It helped both Wall Street and Main Street, and bought precious time for the fiscal response to get underway. This Fed’s policies accompanied a strong expansion before the pandemic-related shutdowns, and a rapid V-shaped recovery afterwards. But with the dramatic exception of the COVID shock last year, let’s face it—this Fed has had a relatively easy ride. Low and stable inflation allowed the central bank to deploy an ever-more expansionary monetary policy without visible damage to the macro environment.

At last year’s Jackson Hole symposium, the Fed unveiled its new monetary policy framework to lift inflation above its long-term 2% target. Careful what you wish for. Inflation is now running over 5% and has already been higher for longer than the Fed had anticipated. With a strong recovery in consumer demand and persistent supply bottlenecks, inflation risks remain to the upside, and high inflation readings will likely show a high degree of inertia. While monetary policymakers and most investors seem still convinced that high inflation will be short-lived, consumers and businesses are much less sanguine.

In fairness, some Fed officials now openly acknowledge that loose monetary policy can’t address shortages of labor and materials and is therefore adding to inflation pressures rather than to activity and employment.

NOW COMES THE HARD PART

Hence, the macro costs and risks of persistently loose monetary policy have now come in plain sight. I don’t fear runaway inflation. But, I do think month after month of 4%-5% inflation can bring us to a very unpleasant crossroads: either wage growth will accelerate significantly, dis-anchoring inflation expectations, or higher prices will keep eroding purchasing power, undermining the recovery.

The latter would be paradoxically counterproductive, because this recovery no longer needs massive monetary stimulus. Underlying fundamentals remain strong. While the Delta variant has caused a resurgence in new COVID-19 cases, vaccines are proving highly effective in preventing severe health consequences; this should allow the current robust economic rebound to continue to unfold in the United States and globally.

So, I think it’s high time for the Fed to tighten policy. The most recent Federal Open Market Committee meeting minutes showed that officials have started to discuss when and how to “taper,” i.e., to start reducing asset purchases. Most analysts expect tapering will be announced in November-December, with rate hikes perhaps in late 2022 or 2023. This is a very timid start. If the current monetary policy stance was appropriate when COVID-19 struck over a year ago and the economy was shut down, it can’t possibly be appropriate now that we have vaccines, a strong recovery and record fiscal stimulus.

The focus on inequality at Jackson Hole highlights one more reason for the Fed to change its policy stance. Persistently loose monetary policy has exacerbated wealth inequality by boosting asset prices, as richer households hold a higher share of assets. But now we are getting a double whammy with higher inflation, which acts like a regressive tax. Lower-income households spend a bigger share of their incomes, so they get hit harder by rising inflation. And over the past several months wages have declined in real terms, as nominal compensation has not kept pace with consumer prices. So, if the Fed is concerned about inequality, its first priority should be to taper its way to a less uneven economy.

Financial investors will be following Fed comments from Jackson Hole closely for any signals on the timing and pace of tapering, and of future rate moves. They will be watching nervously, and that’s what makes the Fed’s challenge harder.

A MORE CHALLENGING RISK/REWARD BALANCE FOR INVESTORS

Rich asset valuations are increasingly a concern. Markets have been moving well in advance of economic data points, and many fixed income sectors are now trading at valuations reflecting a close to best-case recovery scenario. While I am constructive on the fundamental backdrop and the health of the underlying economy, the risk/reward balance is getting more unfavorably skewed in many areas of the fixed income universe as well as in other asset classes.

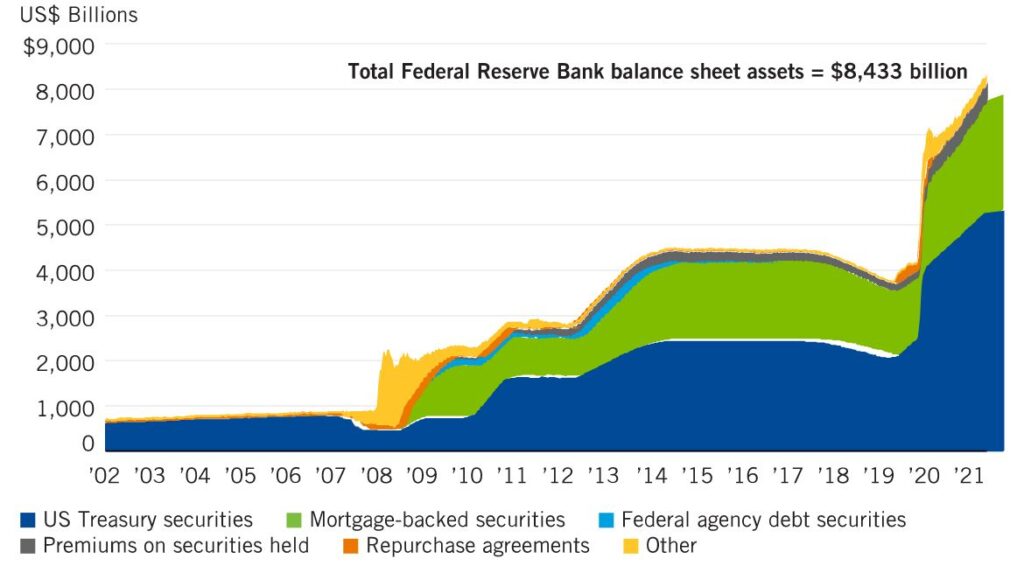

With the best macro scenario already priced in, asset prices become even more sensitive to Fed policy. Over the last many years, the Fed has relaxed policy every time asset prices have wavered. After a timid attempt at tightening, in 2019 the Powell Fed cut interest rates and then effectively relaunched quantitative easing (QE) (see my “ On My Mind: Oops! They QE’d Again ,” January 23, 2020). In his careful cosseting of financial markets, Powell followed in the footsteps of his predecessors Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke. Markets have been dependent on the Fed for a very long time.

MARKETS HAVE BEEN DEPENDENT ON THE FED

Federal Reserve Bank balance sheet: Total assets (December 2002–August 2021)

Source: Federal Reserve. As of August 18, 2021.

That’s why the next six months will likely define the legacy of the Powell Fed’s current term: the case—and the need—for tightening policy has never been stronger, and financial markets have never been more dependent on the Fed. That’s why this Jackson Hole meeting is worth paying attention to. It’s time for the Fed to recalibrate its policy toward better limiting financial stability risks and help us move to a less uneven economy. It’s a hard decision, I know. It always will be. To misquote R.E.M., Leaving QE, never easy.

Investors should be prepared for increased volatility as the markets try to interpret and anticipate the likely changes in policy regime. I continue to expect an above-consensus rise in bond yields, and limiting duration remains one of our main underlying strategy themes. Selectivity and active management are of the utmost importance, in our view. With valuations a growing concern and the risk of rising interest rates, we believe the only way to navigate through this challenging market environment is to focus on in-depth, fundamental research to uncover attractive opportunities.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Stock prices fluctuate, sometimes rapidly and dramatically, due to factors affecting individual companies, particular industries or sectors, or general market conditions. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Investments in lower-rated bonds include higher risk of default and loss of principal. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Changes in the credit rating of a bond, or in the credit rating or financial strength of a bond’s issuer, insurer or guarantor, may affect the bond’s value.

Actively managed strategies could experience losses if the investment manager’s judgment about markets, interest rates or the attractiveness, relative values, liquidity or potential appreciation of particular investments made for a portfolio, proves to be incorrect. There can be no guarantee that an investment manager’s investment techniques or decisions will produce the desired results.