The Chinese government’s policy setting is guided by its core mission of stabilising growth, containing risks, encouraging equality and equity. Understanding this can provide a key source of alpha for investors. At the same time, experience, on the ground presence and active management will be needed, more than ever, to navigate China’s changing regulatory landscape.

The regulatory crackdown on China’s online education sector in August has triggered concerns that other industries could also come under the government’s radar. This has caused a sell-off in Chinese equities as investors reassess the risk premium associated with investing in China. Understanding China’s macro policy cycles has always been key to investing in the Chinese equity market. Historically, government policies have significantly influenced the movements in the China A-share market.

Navigating the changing regulatory landscape

Lessons from the past show that the Chinese government tends to encourage new and emerging sectors and tightens regulations when the associated risks grow. At the start of the 21st century for example, China’s banking sector had benefitted greatly from indirect financing, implicit national credit guarantees, and attractive interest rate spreads. Banking stocks outperformed as a result. However, since then, interest rate liberalisation, higher capital requirements and a greater emphasis on asset quality have compressed banking margins and tempered the sector’s share price performance. Investors may also recall in 2013- 2015, when the peer-to-peer (P2P) sector attracted significant amounts of capital and enjoyed strong growth. Rising risks eventually resulted in tighter regulations which caused the P2P sector to contract.

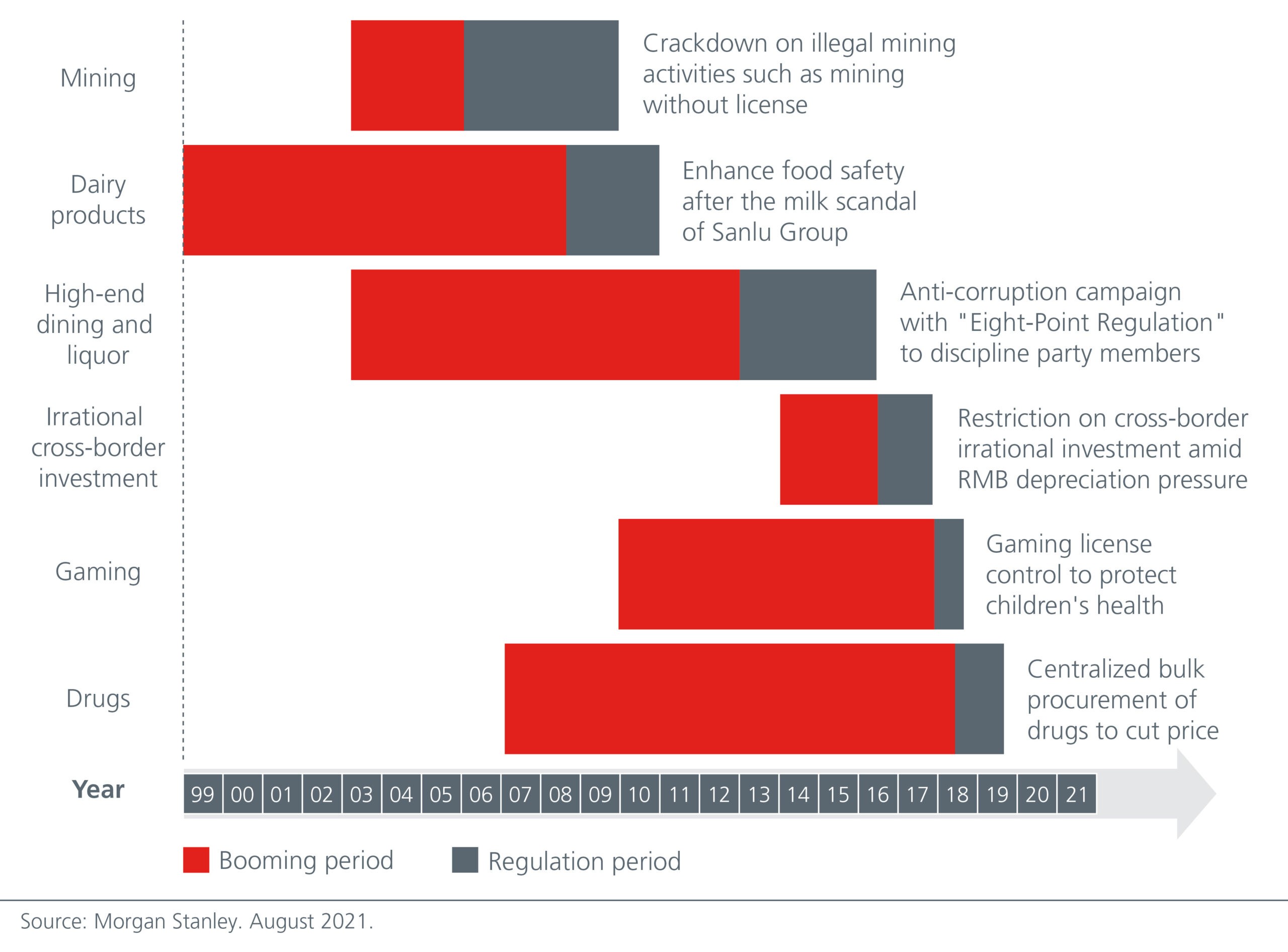

While the new regulations on China’s online education sector have been harsher than expected, the policy direction was no surprise. The Chinese government had over the past few years actively promoted the “equality of education” and imposed multiple restrictions on private schools. Changes to the sector therefore have been a long time coming. For the internet sector, business models and regulations would need to adjust as the sector matures and data security becomes increasingly important. As China’s economy grows and evolves, tighter regulatory curbs can be expected on sectors which have been allowed to enjoy exponential growth in the past. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. China’s regulatory cycle

Investors will need to navigate the potential regulatory risks in China carefully. Lessons can be drawn from China’s real estate industry where repeated tightening measures in the form of mortgage and property sale restrictions caused the sector to de-rate over the years. The falling allocation to the real estate sector amongst China’s onshore equity mutual funds since 2013 suggests that investors may not want to go against policy headwinds.

More than ever, experience, on the ground presence and active management will be needed to navigate China’s changing regulatory landscape. Investors would also need to distinguish policy messages from the noise coming from think tanks and other China observers.

We believe that there are still attractive opportunities even within sectors which may have been affected by negative investor sentiment. For example, we look to benefit from China’s rising urbanisation rate by investing in property management and pre-fabrication companies instead of property developers. Meanwhile, although tighter regulations may affect pharmaceutical companies or manufacturers of healthcare equipment, there are opportunities within the medical aesthetics service sector.

The intent behind the increased regulatory oversight on the pharmaceutical companies and healthcare equipment manufacturers is similar to that of the education sector – a desire by the Chinese government to reduce cost pressures on the households (i.e. medical costs), and to enhance social welfare and equality. Some of these measures which include bulk procurement on drugs and selected medical equipment have been rolled out over the past few years and the policy trend is well recognised by the market, although investor sentiment may fluctuate from time to time.

The tighter regulations on the medical aesthetics sector on the other hand, focuses more on regulating industry competition and improving consumer safety. While regulation can affect the competitive landscape, it is unlikely to stop China’s consumption upgrade trend, in our view.

Why China A

As China’s headline GDP growth declined over the last two decades, China’s pace of reforms has picked up, which should result in more sustainable, higher quality and equitable growth. China’s growth engine has shifted from investment to consumption. With consumption accounting for only 56% of China’s GDP, versus 82% in the US and 75% in Japan1, the upside potential to the economy is tremendous. Reducing China’s income inequality will help to lift overall consumption.

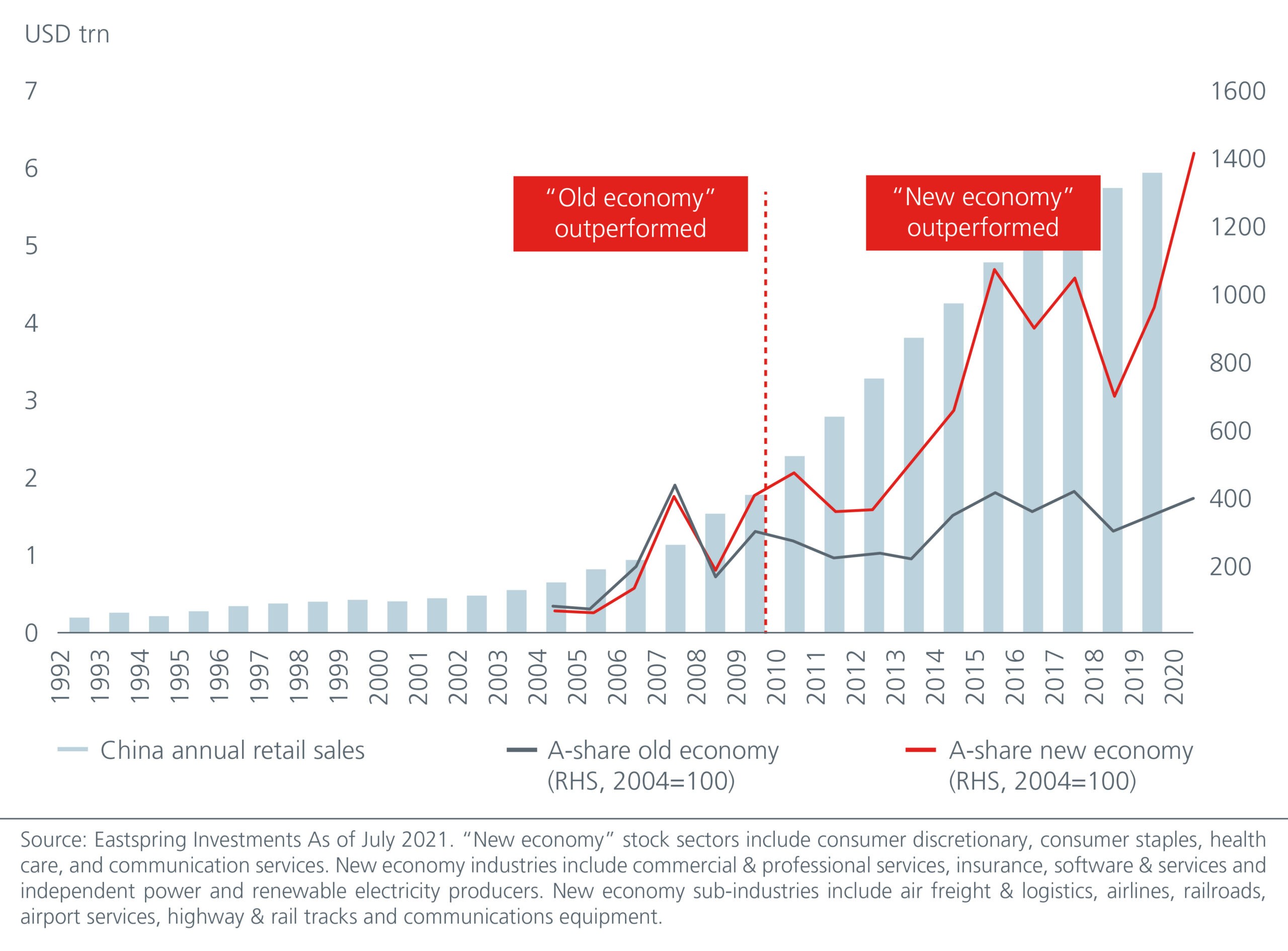

Given these structural changes, the government has proactively sought to encourage new growth sectors while trying to contain overall leverage and potential systemic risks post the Global Financial Crisis. That is why the government emphasised “mass entrepreneurship and mass innovation” during 2013-15, while rolling out tightening measures on the property sector as well as new rules on the asset management sector in 2017. The government has also increasingly realised the importance of environmental protection and have tightened emission requirements as well as implemented energy consumption quotas for various sub-sectors within the materials sector. These regulatory changes, together with slowing economic growth, have weighed on the property and banking sectors, what we refer to as “old economy” sectors.

As China’s economic growth model evolved over the years, new economy sectors which include commercial and professional services, insurance, software and services as well as independent power and renewable electricity producers, have outperformed. Fig. 2. In fact, the top 100 most widely held A-share companies by foreign investors, comprising mostly of consumption, healthcare, technology, and advanced manufacturing stocks have risen 219% since 2016 on the back of strong earnings growth and a re-rating. The remaining stocks in the A-share market declined 24% over the same period.

Fig. 2. New economy sectors outperformed post the GFC

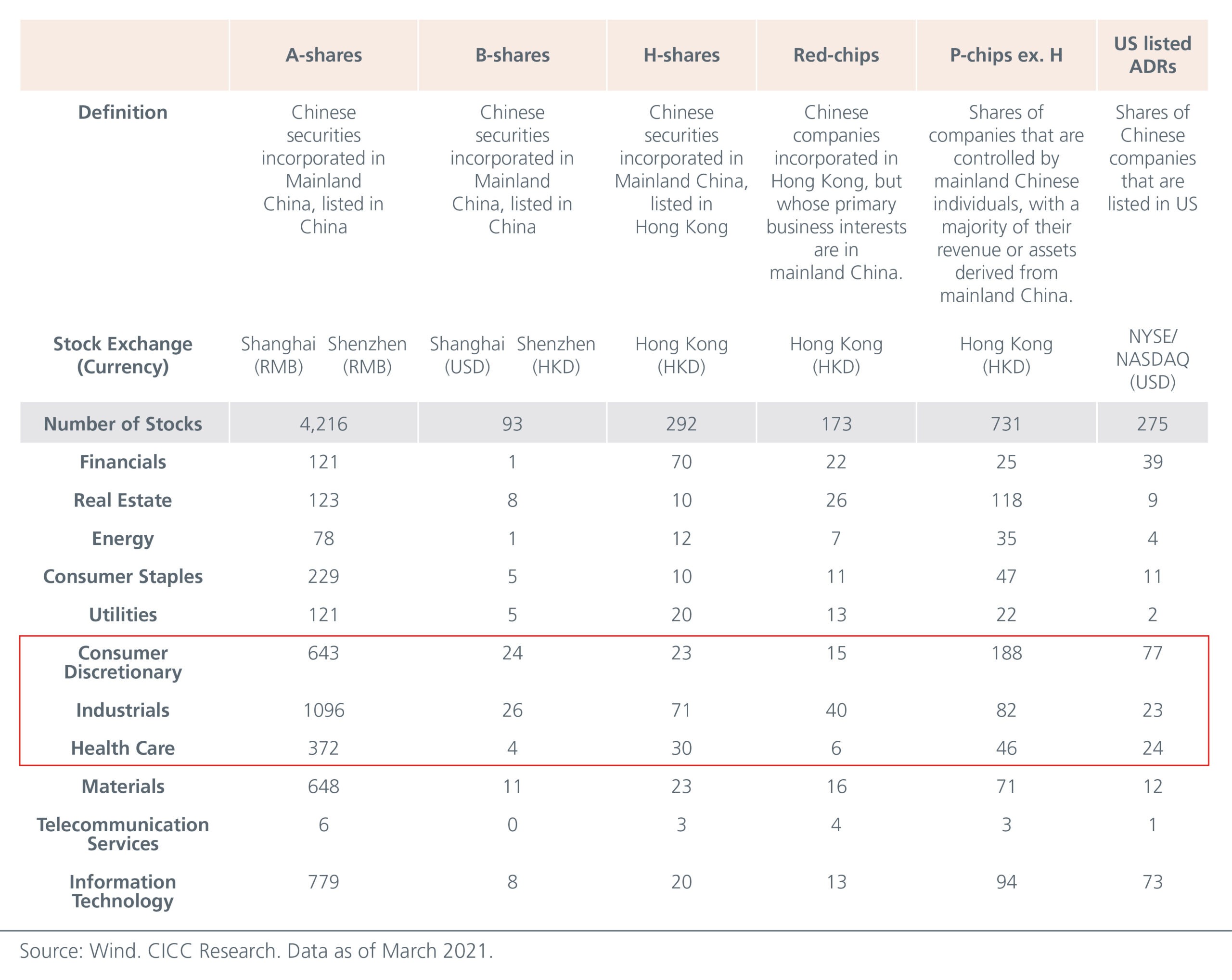

While there are multiple ways to gain exposure to these new economy sectors, the China A-share market offers investors higher exposure to the consumer, healthcare and manufacturing sectors. These sectors are aligned to the government’s national objectives and have received significant policy support – a development that may have been overshadowed by the recent regulatory concerns in the education and internet sectors. Meanwhile, the China A-share market has a lower exposure to the financials and real estate sectors. See Fig. 3. The China A-share market also has significantly less exposure (<0.1%) to the online education and internet-related sectors compared to the H-share (30%) and US ADR (45%) markets.

Fig. 3. Consumer, Manufacturing and Healthcare sectors are key in the China A-share market

Why China A now?

Global investors are currently underweight China by over 4% in their global and regional fund allocations, almost the largest underweight on record. The 2022 estimated forward valuations for the China A-share market (P/E: 13.7x, P/B: 2.1x) appear highly compelling especially against the US market (P/E: 21.3x, P/B: 4.7x)2. Meanwhile the China A-share market trades at a slight premium, on a price-to-earnings ratio, to the MSCI Global Emerging Markets ex China Index (P/E: 13.2x and P/B: 2.1x).

We expect credit and liquidity conditions in China to become more accommodative in the second half of 2021 as the government responds to slowing growth amid rising infections from the delta variant of the COVID-19 virus. Policymakers may also consider easing in order to offset the tightening credit conditions caused by the recent volatility linked to Evergrande and Huarong Asset Management. Historically, domestic policy easing has been favourable for the China A-share market.

While investors may have shied away from China stocks on the Hong Kong and US stock exchanges, the China A-share market has enjoyed robust inflows. From January to June 2021, inflows into China A-shares via the Stock-Connect reached USD 33 bn, surpassing 2020’s total inflows of USD 31 bn. With foreign ownership of China A-shares currently only standing at 4.5%, the potential for outperformance over the medium to long term is significant.

The Chinese government’s policy setting is guided by its core mission of stabilising growth, containing risks, encouraging equality and equity (稳增长、防风险、公平公正). The new economy sectors in the A-share market have significantly outperformed the overall market, reflecting the fundamental and policy changes in China. Understanding the government’s intent will provide a key source of alpha for investors and continues to be a core component in our investment process.