Executive summary

A slowing in the pace of growth and fears about the spread of the Delta variant of Covid-19 have recently led financial markets to question the reflation trade. We just view this as a tempering of over-exuberant market expectations. Ultimately, growth is still going to be very strong. Global activity is anticipated to expand by 6.4% in real terms and 9.8% nominally in 2021 according to JP Morgan. Examining the three largest drivers for economies currently: we are witnessing a boom in goods consumption with services accelerating as lockdown restrictions ease; inflation has jumped – a good proportion of which will prove to be structurally sticky rather than transitory – and employment is recovering, albeit with lower participation levels until people are enticed back into the labour force.

The bond market reaction to the shift in the reflationary narrative can neatly be summarised as duration having moved too far and credit being too sanguine about the price of risk. We have opposed the movement in government bond yields, taking duration in the strategic bond funds down from 3.5 years at the end of Q1 to 2.5 years at time of writing as US 10-year yields reside at 1.25%.

Investment grade credit is expensive compared to its own history and so fund weightings are below our neutral levels. There might not be an immediate catalyst for investment grade credit spreads to widen, but expensive valuations and stretched investor positioning sends us a strong signal that there will be a much better chance to buy in the future. High yield is better value provided one focuses on the quality end of the spectrum: excluding CCC-rated credits and the energy sector, the spread is just below 300 basis points. We retain our quality bias in high yield; the compression between CCC credits and BBs has gone too far and would rapidly widen in any period of risk aversion in the markets.

Macroeconomics

Financial markets have questioned their own enthusiasm around the effects that vaccine programmes were going to have on the recovery from the crisis. To be clear, this is not about vaccine efficacy, it is about over-exuberant expectations being deflated. The Covid-19 Delta variant cases are picking up globally. The UK is a petri dish while cases are increasing from lower levels around continental Europe and there are some very problematic hotspots in parts of Asia, such as Indonesia. Case growth is also picking up in the US, with states that have lower inoculation rates seeing the faster expansion in infection rates.

So far, vaccines have predominately broken the link between cases and hospitalisations. Recent figures from both Israel and the UK show an approximate 92% efficacy against hospitalisation for those that have received two doses of the Pfizer or Oxford/AstraZeneca shots respectively. The pace of vaccination by country has varied significantly. The world will have had enough supply to inoculate the entire population by the end of 2022 – hopefully a more concerted global effort will be made to accelerate deployment in developing nations.

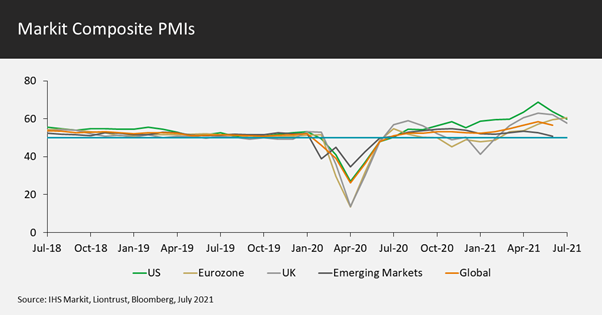

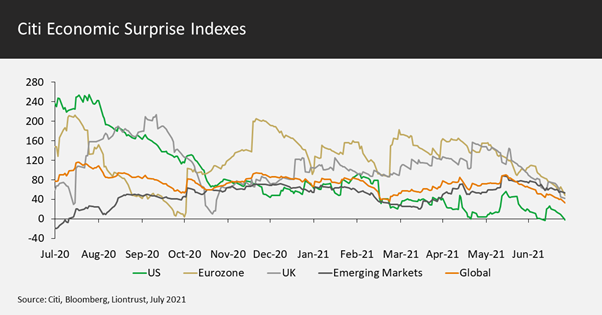

Some of the pick-up in growth was already decelerating before Delta cases started increasing. We attribute this to a combination of supply chain bottlenecks and unrealistic expectations of what level of growth is achievable. Purchasing Managers’ Indexes have retraced from their peak, as shown below:

As a reminder, a reading above 50 is expansionary so this shows that it is merely the pace of expansion that has slowed. Economic forecasters had got ahead of themselves, however. Hard economic data points have subsequently disappointed relative to these forecasts, generating negative surprises.

Variations in the rate of growth are very much a second derivative – the first derivative is growth itself which is incredibly strong still. JP Morgan’s economics team estimates that real global growth in 2021 will be 6.4%. Add in anticipated inflation of 3.4% and that’s a nominal growth rate of 9.8%. This can be broken down into forecast developed market real growth of 5.7% with a 3.3% inflation rate and emerging market economies expanding by 7.4% in real terms plus a 3.5% rise in prices. As we discussed in our last quarterly strategy piece, it is an uneven recovery; output gaps are rapidly closing but, for example, the US will reach pre-crisis extrapolated trend levels of economic activity far sooner than most other developed markets.

Examining the three big drivers of growth for the foreseeable future in turn:

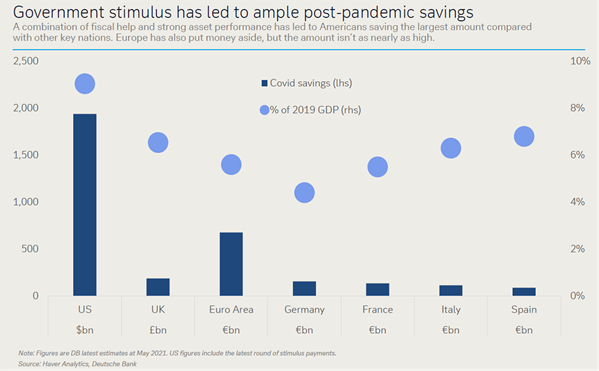

Consumption: Consumer confidence surveys have come off their recent highs, but demand for services is huge. Services are likely to significantly increase their wallet share of consumer spending as more activities are permitted when virus restrictions are eased. Wage inflation is happening, but even if it wasn’t, the increase in excess savings during the pandemic can lead to a sustained consumption impulse over the next few years. The size of the savings surplus is illustrated in Deutsche Bank’s graphic:

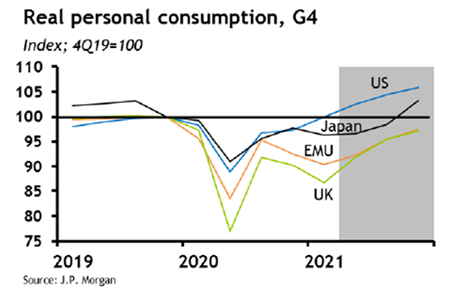

Obviously, not all of the excess savings will be spent, but we would envisage at least 70% of the excess eventually being used to bolster consumption. As a reminder, the US consumer represents over two thirds of the US economy and is larger than the whole of the Chinese economy; JP Morgan’s [July 2021] illustration of personal consumption in key economies shows that the US is particularly strong:

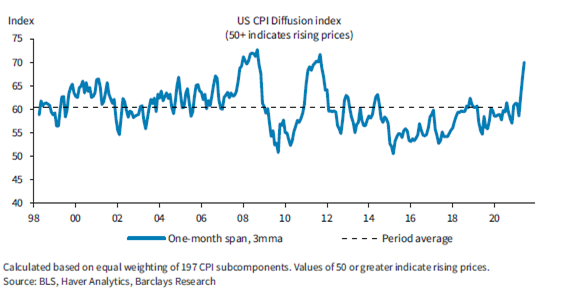

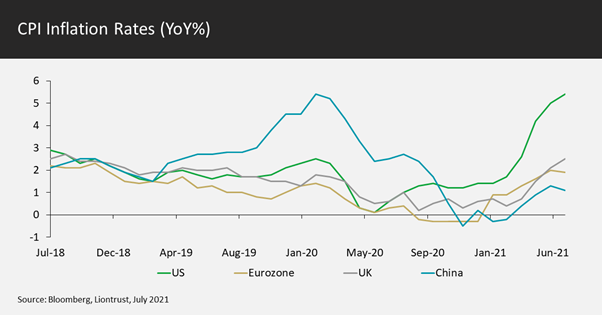

Inflation: The first wave of reopening has seen goods demand swamp supply so some inflation was inevitable. There are quirks in the inflation data that will be temporary in nature. A good example is used car prices: these have been soaring due to lower than usual new build car availability and consumers’ aversion to using public transportation systems. Whilst a retracement in some elements, such as used car prices, is highly likely, there are enough underlying constituents of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket exhibiting increasing prices to illuminate the trend. This is illustrated by Barclays’ US CPI diffusion index [July 2021].

Any sector that is deemed Covid crisis sensitive is seeing a ramp up in prices during reopening. The services inflation impulse is growing. Owner Equivalent Rents (OERs) are picking up too, adding to the heavyweight CPI constituents seeing upward momentum. So, whilst US inflation at 5.4% will not be sustained, we will not see a quick return to the 2% level as we believe that some of the inflation impulse is structural rather than cyclical.

This can start to become self-fulfilling if it feeds into consumer expectations and wage demands. Wage inflation is increasing across earnings cohorts and this has led us to question whether this is partly driven by a lower labour force participation rate.

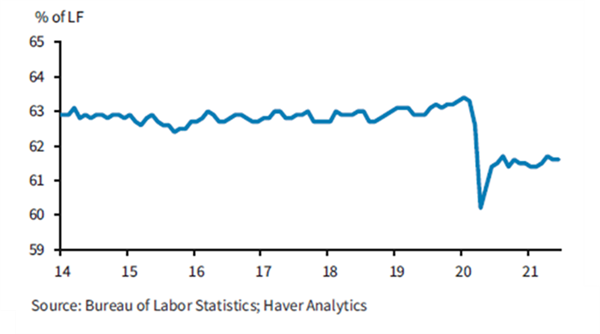

Unemployment: US unemployment is still 6.8m below its pre-crisis peak or 8.8m below the extrapolated trend line. So why are we seeing wage increases with such an employment shortfall still? As alluded to above, this is partly due to participation rates as job openings are at a record high. Barclays’ chart [July 2021] shows that labour force (LF) participation has dropped below pre-pandemic levels:

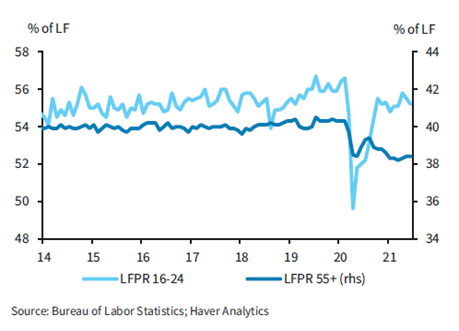

Some of the unwillingness to work will naturally abate when the additional pandemic unemployment benefits end for about 70% of the beneficiaries on September 8th. The biggest gap between before and after is in the 55+ age group:

Maybe the willingness to work for this category is permanently impaired, after all, real estate prices and stock markets have gifted elder generations a lot of wealth. For the rest of the workforce, we assume there will be a return to the labour force after September. The closing of the employment gap should then accelerate. Most temporary layoffs have either been re-hired, become permanent layoffs or retired; so, to boost employment further there also needs to more new job creation. One obstacle to future hiring is if there is a gap between the skills that those returning to the labour force have and those that the job creators require. Whether such obsolescence exists will become clearer over the coming quarters.

Rates Positioning

The next move for most central banks is towards tighter monetary policy. Rates have already risen in 2021 across Latin America and Eastern Europe. Within emerging markets, the notable exception is China where policy has been loosened this year. Tightening in the biggest developed markets will be through a combination of tapering of quantitative easing (QE) and rises in market yield levels. Obviously, a slowing in QE is technically merely an adjustment to the pace of easing, but the signalling impact is paramount. Regarding market yield levels, having started 2021 with its worst quarter since the early ‘80s, the US Treasury market has retraced roughly half of its yield rise. At the short end, there is now only one hike priced in over the next year, with nothing in Europe and half a hike in the UK. From a cross-market alpha perspective, we note that New Zealand’s government debt is pricing in three hikes over the next 12 months.

What has been fascinating is that even when rate hikes are being priced in, the destination (the level at which rates are expected to peak in this cycle) has not changed, only the timing altered. It seems premature to already be talking about terminal rates and a low equilibrium real rate (R*) when the raising cycle in developed markets has not yet begun. With inflation likely to be stickier than many forecast, the financial markets’ benign view on where rates are heading is likely to be challenged over the next few quarters.

The recent fall in government bond yields could partly be attributed to the lack of net supply in the US Treasury market. Bond markets are very distorted so their signalling impact on the macroeconomic front has lost a good deal of is potency. One issue that we don’t believe is presently driving yields is the US debt ceiling; the limit will probably be reached in the next month or two, but we anticipate a rapid resolution as has happened on most prior occurrences.

We have opposed the movement in government bond yields, taking duration in the Liontrust Strategic Bond and Liontrust GF Strategic Bond funds down from 3.5 years at the end of Q1 to 2.5 years at time of writing as US 10-year yields reside at 1.25%. For the foreseeable future we envisage maintaining duration between 2.5 and 3.5 years provided that Treasury yields, using the 10-year as a proxy, remain in the 1.25% to 1.75% range. If US yields were to fall to close to 1%, we would then reduce the duration below 2.5 years. The recent rally in yields has unsurprisingly seen a big flattening in yield curves. We maintain our preference for the belly of the curve – those bonds with a maturity in the 5-15 years bucket.

Active cross-market alpha trades in the funds include being long Swedish debt relative to German Bund duration. Within Europe, we think the UK is particularly expensive and have a short duration position in the strategic bond funds. We have recently entered a long New Zealand versus Australia position; the former has been a huge underperformer with rate rises now already in the price. Absolute market levels are still expensive, so we have sold Australian bond futures to extract the duration. The market there has become too concerned about shorter-term lockdowns and is underestimating the pent-up demand once lockdowns abate. Finally, we retain our Canada versus the US box trade, being long Canadian 5-year debt and short the 10-year maturity with the opposite positioning being taken in the US. This is the third time this year we have taken advantage of this market mispricing.

US inflation breakevens have retraced roughly half of their year-to-date gains since the middle of May: the 10-year breakeven, having peaked over 2.50%, is now nearer to 2.25%. We would want this figure to be approaching 2% before the funds would reinstate a position in TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Securities).

Spread product

Balance sheet fundamentals are improving as earnings increases materialise, so both leverage and coverage metrics are now trending in the correct direction. There has been a huge improvement in credit ratings drift too; this is particularly the case with regards to BB and B rated issuers.

Mergers and acquisition activity has been increasing, epitomised by the trend early this year for SPAC (Special Purpose Acquisition Company) offerings. It does feel more like 2005 and early 2006 rather than the peak of egregious merger and acquisition (M&A) activity in late 2006 and early 2007. Capital expenditures are also on an upward trend, despite utilisation rates languishing at only 75%. We would posit that the underlying utilisation rate is higher and that some of the denominator is now obsolete.

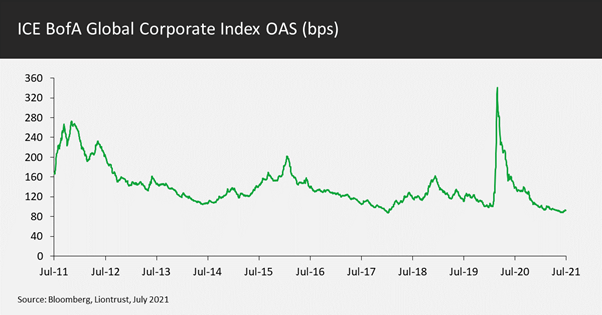

Investment grade credit is expensive compared to its own history. The spread on the global corporate index of 93 basis points is close to the tightest level we have seen over the last decade:

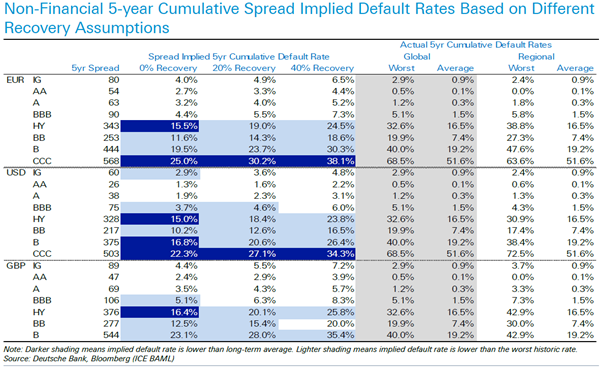

One still gets compensated for default risk in investment grade, as can be seen in these numbers from Deutsche Bank [July 2021]:

However, there are other risks including downgrade risk and illiquidity risk that the credit spread also needs to compensate investors for.

High yield is better value provided one focuses on the quality end of the spectrum. Excluding CCC-rated credits and the energy sector, the spread is just below 300 basis points. We retain our quality bias in high yield. The compression in spreads between CCC- and BBs has gone far too far – the former category is now not compensating you for its inherent default risk.

We continue to like quality credit that offers a decent spread breakeven, a measure of how much the spread can widen by over the next 12 months before one loses money on the position. As a proxy, the iTraxx Xover index has a duration of about 5 years; if the spread were to reach 260 basis points, this would represent a breakeven over 50 basis points (260/5) and be attractive for the strategic bond funds. The Liontrust High Yield Fund already has a larger exposure to the underlying issuers’ bonds so will veer toward CDX HY if we get the opportunity to add generic risk over the summer.

Investment grade supply is still abundant with over US$400bn issued by both financial and non-financial companies in the first half of 2021 in the US dollar market alone. This is below last year’s level when companies were desperate for extra liquidity, but still high by historic standards. High yield gross and net supply is running at record levels on both sides of the Atlantic. It is being easily absorbed in markets awash with cash and searching for yield. Leveraged loan issuance is also booming, as one would expect with the rise in M&A activity. Net flows into the universe of fixed income mutual funds are a small negative in 2021, multi-asset professional and personal investors preferring riskier asset classes.

Sentiment indicators are not showing any significant warning signs. The US 2s10s curve has recently flattened but is still over 100 basis points. The uptick in VIX in the last month from 15 to 19 is insignificant on any longer-term scale; on its own this measure does point toward the markets not shunning the desire to take risk.

With credit markets having been so strong there has been the inevitable compression in the basis, the difference between the spreads on corporate bonds and their credit default swaps (CDS). Examining market positioning in CDS shows that the investor universe is very long credit risk; this is a sign that the market is being too bullish on risk. There might not be an immediate catalyst for credit spreads to widen, but expensive valuations and stretched investor positioning sends us a strong signal that there will be a much better chance to buy in the future.