Developments in real bond yields and breakeven rates on inflation-protected bonds suggest how rest of the fixed income market will perform. That’s particularly relevant now.

Real yields always matter. But bond investors would do well to pay particular attention to what’s happening with them now. That’s because an environment of rising US real yields and falling breakeven rates on index-linked US Treasury bonds suggests fixed income and currency risk markets should brace for more pain.

Our model of US real yields versus index-linked inflation breakeven rates suggests that markets are destined for yet more US dollar appreciation, weakness in emerging market bonds and currencies, and declines in high yield bonds; investment grade and US Treasuries, by comparison, will likely remain rangebound.

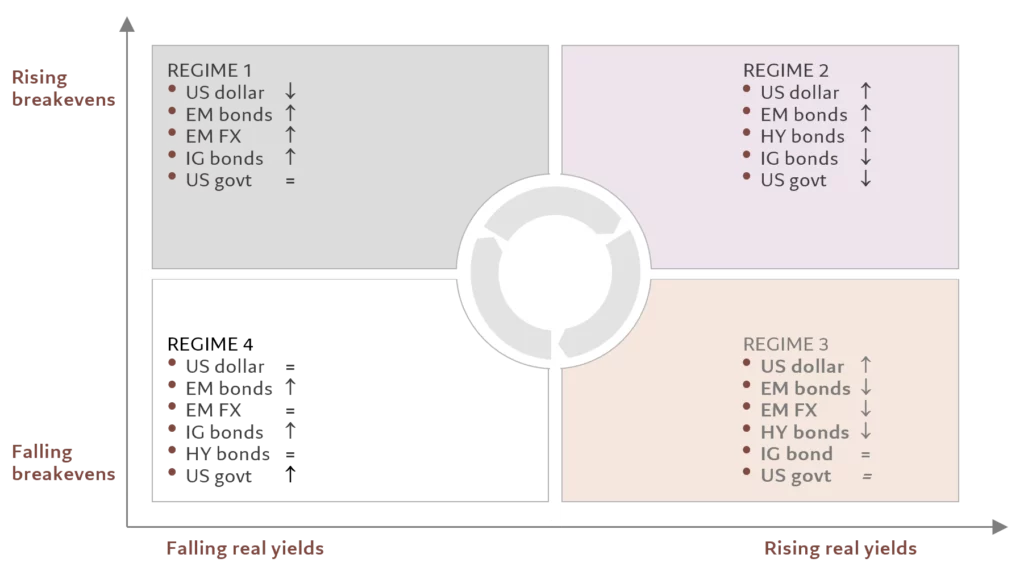

Broadly speaking, the model outlines four different market regimes, depending on whether real yields and breakevens are falling or rising – more detail can be found in this article. Each of these regimes has different implications for fixed income assets and currencies (see Fig. 1)

Fig. 1 – Real yield regimes

So, for instance, during periods of falling real yields and rising breakeven rates – as occurred between September and November of last year on the back of rising inflation expectations amid pent-up demand and supply shocks – the dollar tends to weaken while risky bonds and credit tend to appreciate. Or, a period of rising real yields and rising breakeven rates – which happened in the wake of the Ukraine invasion and led the US Federal Reserve to abandon its ‘transitory inflation’ narrative and begin hiking rates – tend to lead to a rise in the dollar but falls in Treasuries and investment grade credit.

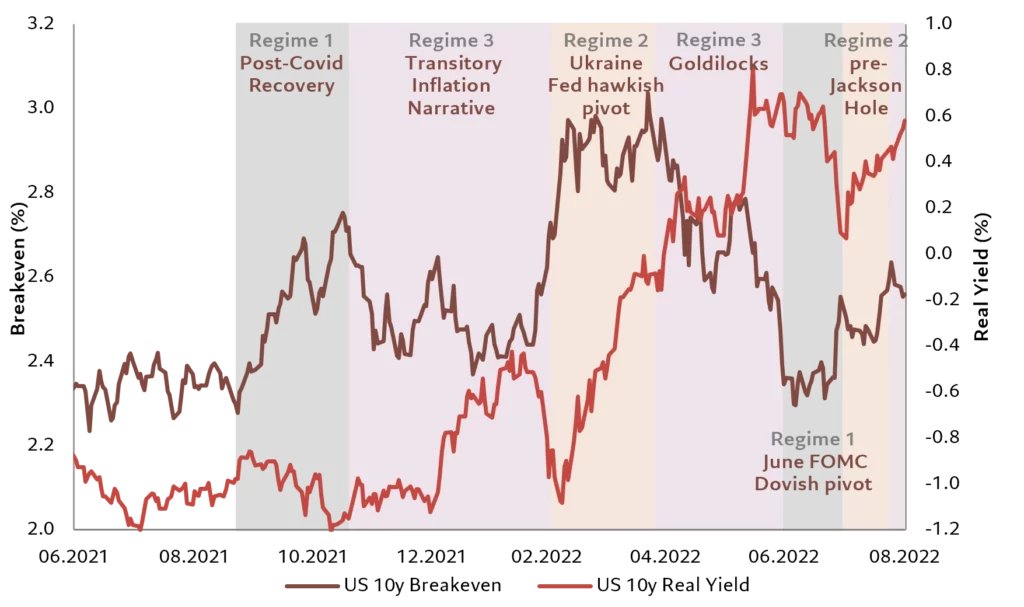

In normal times there might be slower transitions between longer-lasting regimes. But over the previous year we’ve seen dramatic changes in the macroeconomic and monetary narrative – from central bank hawkishness to dovishness and back again. Over this period, the upper bound of the US Federal Funds Target Rate has moved from 0.25 per cent to 2.5 per cent against a backdrop of consumer price inflation that peaked at 9.1 per cent, its highest since 1981. As a result, since August 2021, we have cycled through several regimes of our model {see Fig. 2].

Fig. 2 – Regime change

Real yield regimes vs US 10 year breakeven and US 10 year real yield, %

And then there was the latest shift. In August this year, Fed policymakers made it clear they were concerned that inflation wasn’t falling as fast as they’d anticipated and that they didn’t want to make the same the mistakes of the 1970s – when the Fed’s anti-inflation measures were repeatedly ended prematurely. This culminated in chairman Jerome Powell’s hawkish Jackson Hole speech. There he made it clear that the Fed’s overarching focus was to bring inflation back to its 2 per cent target. This, in turn, required a period of below trend growth and softening labour market conditions – “pain” in his words. Returning to a neutral rate of interest wasn’t sufficient. Instead, he argued, a restrictive policy stance would have to be maintained for some time.

That puts us in a regime of rising real yields and falling breakeven rates (regime 3 in Fig.1).

Investors hoping for a quick turnaround should take note. Recent history has had the Fed quickly reverse course on policy tightening in the face of weakening growth. But now, as long as inflation looks to resist returning to target in a reasonable time frame, it looks as though the Fed will turn a blind eye to rising unemployment and recession risks.