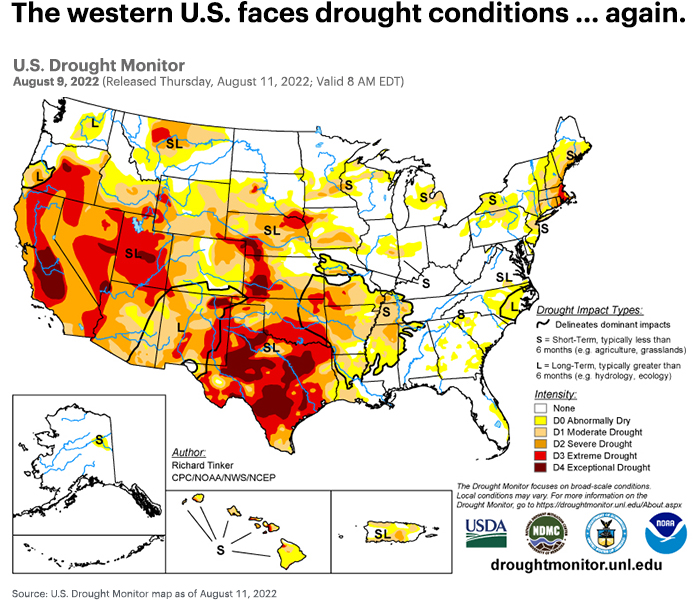

As we write this article in mid-August, authorities across the Rocky Mountains are issuing flood warnings. Monsoon rains have drenched deserts and mountains in Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming, with eight million Americans significantly affected. These extraordinary conditions belie an even more severe and longer-term challenge: the intense drought crisis throughout the western U.S.

The Colorado River Basin’s aridification offers what may be the most consequential example of this crisis. On August 16, following 23 years of more-or-less continuous drought, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) announced the first-ever Level 2a Shortage Condition for Lake Mead’s water level. This prompted the U.S. Department of the Interior to announce that starting in January 2023, there will be sharp cuts in the Colorado River’s supply to Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico as climate change-exacerbated drought continues to deepen the West’s water deficit.

The Department of the Interior called for cutting Arizona’s supply by 21%, Nevada’s by 8%, and Mexico’s by 7%. Combined, these cuts total 4.2 million acre-feet annually: approximately the volume of Lake Okeechobee, according to the Department.

How will the West’s drought affect markets?

Certain trends are emerging:

- Agriculture continues to transform. Cropland acreage is shrinking gradually. Remaining acreage is shifting to higher-value and/or more water-efficient crops. Fallowed land, in some cases, is being repurposed to renewable power generation and ecosystem services.

- Utilities in some regions are enjoying faster growth by developing new grid infrastructure for wind and solar. Others, dependent on river flows for hydroelectricity, could face restricted output.

- Municipalities that depend on tenuous water supply and/or marginally profitable croplands may face increasing challenges.

- Agriculture technology continues to grow through advancements in both equipment and information technology that reduce water demand and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Water infrastructure developers and manufacturers may benefit as systems are forced to upgrade efficiencies and supply options.

High and dry: The Colorado River Basin’s deficit of supply versus demand is increasing

Lake Mead and Lake Powell are now at critically low levels. Continuation of the current supply deficit would compromise associated hydroelectricity production within a few years and require significant additional curtailments of supply to municipal, agricultural, and industrial users throughout the West. The curtailments announced on August 16 would become more severe and affect additional states, including California.

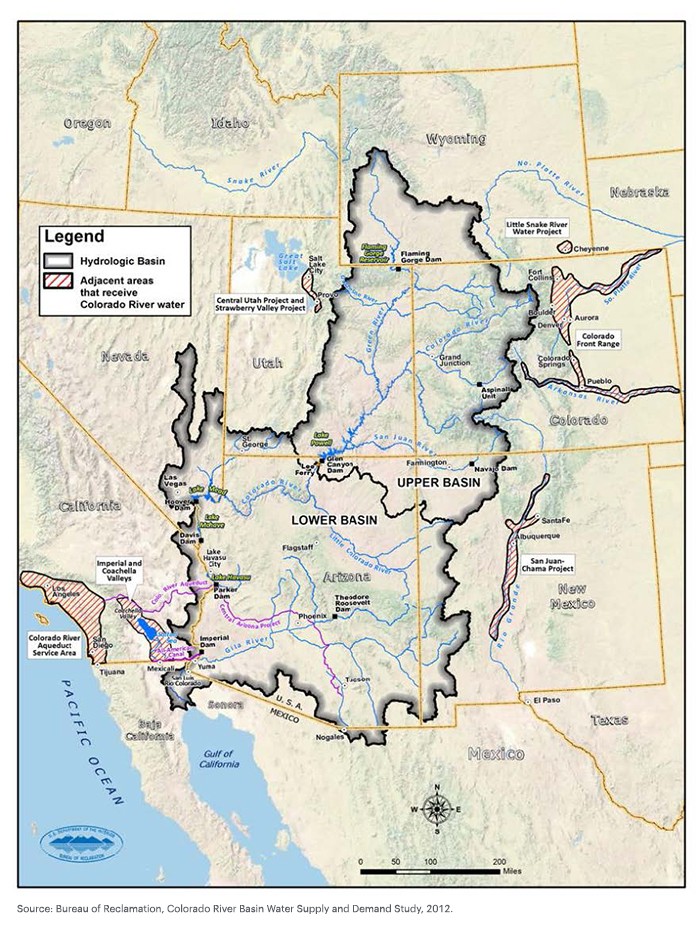

The Colorado River Basin comprises two sub-basins: the Upper (mainly Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming) and the Lower (mainly Arizona, California, and Nevada).

The Upper Basin, where the Colorado River originates, is obliged to deliver fixed volumes to the Lower Basin. This means the Upper Basin must absorb any unanticipated reductions in the flows in the Colorado River—including those that may be climate change-induced—to meet its Lower Basin delivery obligations.

There’s also an obligation to Mexico, raising the risk that Upper Basin states like Colorado will need to curtail users with junior water rights—mainly users near population centers east of the Rockies—in order to supply their growing economies.

Adding to the complex relationship between the basins, minimum elevations are required in Lake Mead and Lake Powell (the nation’s two largest reservoirs) to sustain power generation at associated hydroelectric facilities. For years, the USBR has cautioned that continued drought would test these levels and trigger curtailments downstream. Lake Mead, for example, is now within about 35 feet of breaching a power generation threshold.

This situation highlights two potential events that may concern markets:

- As curtailments happen, we can envision wealthier communities reacting by bidding aggressively for water rights from poorer, financially pressured communities that depend on the rights to sustain their economies. This is a familiar theme: Sustainability risks often affect lower-income communities disproportionately. Anticipating this scenario, new water policies are being designed with the goal of protecting lower-income communities’ interests.

- The historically contentious efforts to rationalize Upper Basin and Lower Basin water sharing could become increasingly volatile. Upper Basin states don’t want to compromise economic growth potential by ceding water supplies to the Lower Basin. Lower Basin states, which have made notable conservation progress, don’t want to forfeit rights they contractually own. Additional friction will not help what are already immensely complicated negotiations, especially if they become litigious. Federal authorities may have to intervene in politically polarized circumstances.

A new shade of green: Renewables and ecosystem services expand on fallowed acreage

Solar development on fallowed and mixed-use croplands is already occurring in regions with declining water availability, no permanent crops, and/or energy-intensive agricultural operations. For example, farmers in California’s Kings County have already leased former croplands for utility-scale solar projects, and several more are in the pipeline.

California isn’t unique in repurposing croplands for solar projects. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimated that certain non-irrigated lands in Colorado could allow 890 square kilometers of solar fields without compromising agricultural productivity.

Repurposing options extend well beyond power generation. Agrivoltaics—placing elevated solar panels above crops—could reduce water evaporation from plants and soil as well as lessen light and heat stress to enhance crop photosynthesis. Also, transpired water cools solar panels, modestly improving their efficiency. While agrivoltaics’ effects on crop yields vary, in some studies total fruit production and water efficiency have doubled for shade-tolerant and temperature-sensitive crops.[1]

Fallowed cropland can also be repurposed to provide a wide range of ecosystem services. Biochar (which stores black carbon produced from organic matter), cover crops, and no-till farming are all being actively evaluated, as are two rangeland management practices: compost and high-impact grazing.

Technology: The next agricultural revolution is unfolding

We believe agriculture technology will remain a vibrant growth area, driven by drought and other secular trends: population and food-demand growth, decarbonization, overuse of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers, more robust communications connectivity, and robotics, among others. Artificial intelligence, analytics, connected sensors, and other emerging technologies could further increase crop yields, boost water-use efficiency, and improve sustainability and resilience across crop cultivation and animal husbandry. Also, various forms of precision farming may allow some currently marginal crops to remain profitable.

Next steps: Focus on solutions

The West’s current drought foreshadows challenging climate events that are likely to grow more frequent and intense in the future. There’s no room for complacency in the affected regions. However, as noted earlier, several positive trends are gaining momentum:

- Agricultural water use in the western U.S. has been declining while the economic value of output has been increasing. This is likely due to increasingly efficient farming practices and technologies and, in some cases, crop selection.

- Urban water use is lower despite population growth. Previous droughts triggered conservation actions that continue to yield water savings, like drought-resistant landscaping, low-flow shower heads, and high efficiency appliances.

- There are encouraging alternative land use solutions for uneconomic croplands.

- Technology solutions are expanding and becoming more cost-effective across the water supply and agricultural value chains.

While it’s impossible to avoid climate risks, it’s our imperative to manage them. Allspring’s Climate Change Working Group and Water Working Group will continue researching, developing, and disseminating frameworks for identifying leaders and laggards in managing climate and water risks as well as identifying promising risk-mitigation solutions.

[1]. Anuj Krishnamurthy and Oscar Serpell. 2021. “Harvesting the Sun: On-Farm Opportunities and Challenges for Solar Development,” [PDF] Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, University of Pennsylvania.