Portfolio Managers Seth Meyer, John Lloyd and Head of US Fixed Income Greg Wilensky encourage investors to carefully consider the value, and source, of their interest rate exposure as opportunities for more attractive risk-adjusted returns may be accessible by active managers across today’s larger and more diversified bond markets.

Key takeaways

- Bond portfolios can act as a hedge against equity market volatility, but both the value and cost of this hedge fluctuate as economic and market conditions evolve.

- With inflation above the yield of the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, investors’ ‘real’ (adjusted-for-inflation) return is likely going to be negative.

- We encourage investors to carefully consider the value, and source, of their interest rate exposure. Opportunities for more attractive risk-adjusted returns may be accessible by active managers across today’s larger and more diversified bond markets

Bond portfolios have long been considered useful as a potential hedge against volatility in the more dynamic parts of an investor’s portfolio, such as equities. Like paying for car insurance, the idea of sacrificing some return to have a lower volatility of overall returns can be perfectly reasonable. But while we are bombarded with advertisements helping us optimise the cost of our car insurance, we don’t get a lot of help making sure we have the right amount of, and are not paying too much for, this ‘insurance’ when we select our bond exposure.

With the current yield on the benchmark Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (Aggregate) near 1.7%, and inflation expected to stay above 2% in the coming years, investors are paying a ‘real’ (after accounting for inflation) cost to hold this benchmark of 0.25% to 0.5% a year.

I’m such a profound believer that timing is everything; I would tattoo that on my arm.”

– Actress Drew Barrymore

There is nothing wrong, in our view, with paying for insurance. But in the same way it’s not very effective to buy car insurance after an accident, the solution to the problem of insurance becoming more expensive is not to cancel your policy. Or, in our case, avoid long-duration (a measure of interest rate sensitivity) assets entirely. Remember that bond yields were, relatively speaking, ‘low’ before the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020. Investors could have complained then that the ‘cost’ of owning Treasuries or a long-duration benchmark like the Aggregate index was too high. But we would venture an educated guess that by the time an investor who had little bond exposure in March 2020 wished they had more, it would have been too late. Timing is everything, but when it comes to owning insurance, we think investors should focus more on how much, not whether, insurance is worth paying for. While one part of that calculation should be its cost, another could be the more personal questions of how much they need or want.

Because the Aggregate index has a long duration, it can see significant increases in value when Treasury yields fall – like they did in early 2020. But this duration has risen substantially in recent years, from a low near six years in 2019 to nearly seven years today.1 That is, the index today offers around 15% more interest rate sensitivity than it did just a few years ago. As such, the Aggregate index is delivering more ‘insurance’ today than it was just a few years ago. Those fearing the worst may rejoice at this news. And those who may have realised substantial gains in the equity market, and want to protect them, may find the news comforting. But for those who think interest rates are more likely to rise than fall, we suggest investors contemplate a shift of some of their bond holdings to a manager that will actively manage the duration exposure, or look to shift some of their exposure themselves.

The problem of low bond yields

If you think of the yield earned on a bond portfolio as a ‘cushion’ to help absorb the potential capital losses should interest rates rise, it should be apparent that the lower the yield, the thinner the cushion. Unfortunately, at the Aggregate index’s current yield, a rise in 10-year Treasury yields by more than 0.25% would negate a year’s worth of positive income from the index. On an inflation-adjusted basis, the maths is even worse: if we assume inflation remains near 2.0%, and the Aggregate index continues to yield near 1.7%, and everything else remains unchanged, 10-year US Treasury yields would have to fall over 0.04% each year to realise a flat real (adjusted-for-inflation) return for the year.2

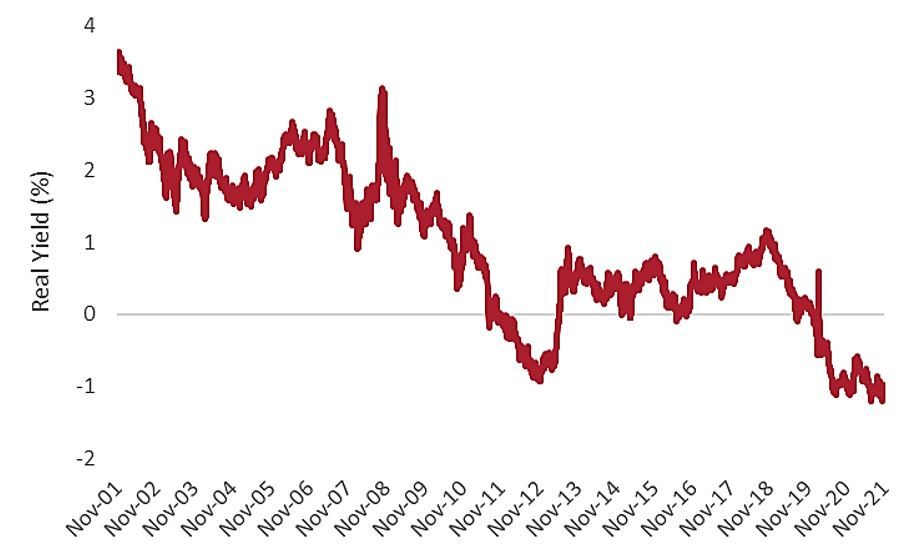

The problem, of course, is bigger than the Aggregate index. Treasury yields are relatively low, foreign government bond yields are even lower in the developed world, and investment grade corporate bond yields are relatively low too. And the problem is not new. Bond yields have been trending lower for over two decades, and that has dragged down the yield of the Aggregate index. This is also apparent when we look at inflation-adjusted, or ‘real’, yields. While the real yield of the 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (Exhibit 1) remained mostly positive over the last decade, it has averaged just 0.08%. Then, in 2020, when Treasuries yields fell, the real yield followed. In our view, it is a good time to evaluate how much insurance an investor wants to own – how much duration they should have in their portfolios – and pay closer attention to its cost.

Exhibit 1: 10-year US real yields

Has corporate bond risk evolved as well?

It is not uncommon for investors dissatisfied with low yields on Treasuries or other investment-grade bonds to consider taking more credit risk in search of higher yields. If this sounds like nearly the opposite of buying insurance, buying corporate bonds has indeed been described as ‘selling insurance’. This is because buying insurance is a decision to pay a fixed amount for protection against uncertainty, while buying a corporate bond is receiving a fixed amount (the yield) in exchange for taking on uncertainty about the credit risk of the company. In either case, the question usually boils down to whether, at today’s prices, the buying or selling is worth it. How much additional return can an investor realise for the additional risk? Put simply, do high yield bonds pay enough additional yield to make the greater risk worthwhile? And has that risk evolved?

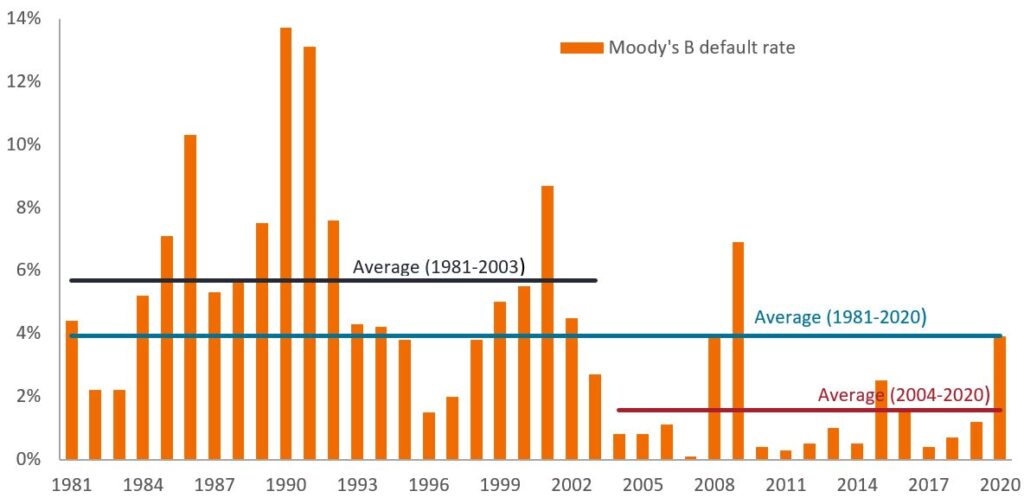

Central bank policy evolves over time, and the trend has been to provide ever greater support for financial markets. Decades ago, Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Alan Greenspan gave confidence to equity markets that there was some level of drawdown the Fed would not tolerate. If things got too bad, Greenspan would bail them out. Subsequent central bankers echoed this approach, extended it to the banking system, and in time this kind of ‘quantitative easing’ – a way of providing liquidity to financial markets without lowering interest rates – became acceptable central bank policy. After COVID-19 struck, the Fed even signalled its willingness to buy high yield corporate debt, albeit through funds and on a small scale. Will the Fed provide even more support in the next crisis? We think so.

Exhibit 2: Default cycles are less pronounced

While Treasuries yields and investment grade corporate bond yields are still relatively low, the spreads in the high yield market are still significantly wider than the previous lows in 2007. But interest rates are low compared to 2007, real rates are even lower, and the Fed, in our view, is more supportive of the market today than it was in 2007. As Exhibit 2 shows, default rates have been declining since the early days of the high yield market. And JPMorgan is currently forecasting a default rate of only 0.65% for the US high yield market in 2021.3 For investors who agree with our assessment that the credit cycle shows little sign of changing direction and who believe the Fed is likely to remain supportive, the high yield markets of the world may merit a closer look in a diversified portfolio.

The Aggregate Index has become less aggregate

High yield bonds are just one example of the opportunities that may lie outside the constraints of the index. While investment grade corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities have long been staples of the Aggregate index, in the last decade other securitised markets have boomed without corresponding representation in the index. Asset-backed securities, commercial mortgage-backed securities and other securitised products can often provide additional yield as well as diversity. Also, the bank loan market and its securitised counterpart, collateralised loan obligations (CLOs), have grown rapidly – with total bank loans now similar in size to the high yield market.

However, an active manager can use all these instruments to dynamically adjust exposures as conditions evolve and the amount, and cost, of the ‘insurance’ an investor seeks to hedge against equity volatility evolves. Knowing how much duration and income is desired from a diversified bond portfolio, keeping in mind their real costs and risks, should always be an investor’s starting point. For those who can achieve their goals through a common industry benchmark like the Aggregate index, the next steps are relatively simple. For those who cannot, we believe the evolution and expansion of the bond markets in recent decades provides a wealth of opportunity to find a workable solution.

2Bloomberg, Janus Henderson, as of 25 October 2021.

3Source: JPMorgan, 2021 Mid-year High yield Bond and Leveraged Loan Outlook, 28 June 2021.