Sitting on a financial powder keg?

Equities are near all-time highs. Defaults are near all-time lows. Levered credit markets are bigger than ever. Spreads are approaching all-time tights, or post Global Financial Crisis (GFC) tights in the case of leveraged loans. Commodity prices have appreciated materially. Housing prices have increased 20% year-over-year. Speculative behavior has been rife within cryptocurrencies, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and meme stocks.

Based on those observations, it seems unfathomable that we are only 18 months removed from the start of a global pandemic that wreaked havoc on financial markets and the manner in which people fundamentally live and interact. Yet, on the back of significant central bank and government support globally, economies and companies have been able to rebound from the lows of 2020 and regain momentum broadly.

Although markets have rallied from their lows in 2020 and general sentiment is improving, there are signs that momentum is beginning to falter. As we look forward, notable concerns have emerged, including:

- Covid-19 variants

- Raw material and input cost inflation

- Price inflation

- Semiconductor chip shortages

- Labor shortages, despite higher wages

- Freight cost increases

- Supply chain bottlenecks

- Geopolitical flare-ups

- Pace and timing of Fed policy changes

- Political agendas ahead of US mid-term elections

These factors may ultimately prove to be ephemeral, but investors ought to not only be mindful but also prepared that the conditions underpinning financial markets are combustible and ripe for a significant market dislocation.

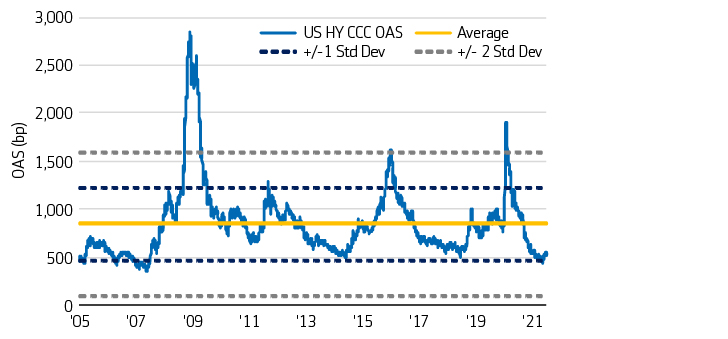

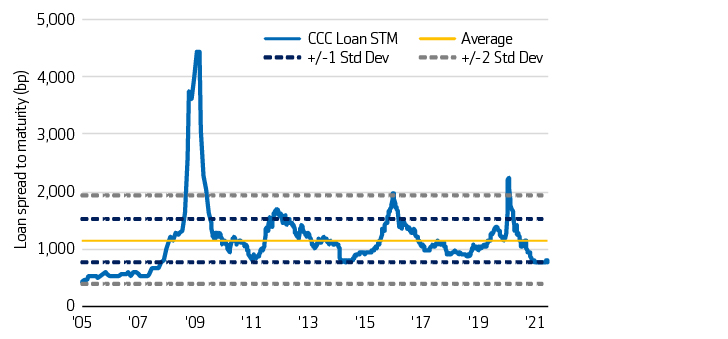

Unwinding of risk in levered credit

Focusing on levered credit, for over a decade, when lower-quality credit spreads historically reached current levels, they rarely remained this tight for a protracted period of time. Instead, levered credit markets were prone to swift price corrections (e.g., 2008, 2011, 2014, 2018, 2020), often realized over a period of 12-24 months after settling at these historically tight levels (Exhibit 1). The catalysts for such unwinding of risk are difficult to predict but can be caused by a variety of factors, such as secular change, geopolitical tensions, monetary/fiscal policy changes, or a shift in global economic growth/inflation expectations.

Further, according to J.P. Morgan research as of September 2021, nearly 25% of lower-quality debt (i.e., rated B3/B- and below) and over $500 billion of high yield bonds and leveraged loans are maturing over the next three years, with roughly $330 billion of debt coming due in capital structures that are $1 billion or less. This maturity wall, in conjunction with historical norms when spreads get this tight, suggests potentially choppy waters ahead in levered credit.

Exhibit 1: Spreads at historical tights

High yield CCC option adjusted spread1

Leverage loan CCC spread to maturity2

1Source: Bloomberg data as of August 2021; Barclays research.

2Source: S&P LCD data as of August 2021; Barclays research.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Regardless of the catalyst(s), spread reversion during periods of volatility is likely to create an attractive and ample opportunity set for prepared investors within levered credit markets. Though the opportunity set is likely to be broad across multiple asset classes, as observed most recently, we believe there is an attractive and under-served niche within leveraged loans that merits additional focus.

A growing asset class with vulnerabilities

The leveraged loan asset class has grown substantially since the GFC, from $600 billion to nearly $1.3 trillion, according to S&P/LSTA data as of August 2021. Demand for leveraged loans typically comes from collateralized loan obligation vehicles (CLOs), leveraged loan mutual funds, insurance companies, business development companies (BDCs), and a variety of other mutual or hedge fund strategies. Importantly, CLOs have become the predominant source of demand for leveraged loans, growing from roughly 50% of the investor base at the time of the GFC to over 70% as of year-end 2020, per Citi research.

As the asset class has grown, with demand for loans spurred in large part by new CLO formation, underwriting standards have generally deteriorated. Based on S&P LCD data pertaining to leveraged loans, leverage has steadily increased, covenants have weakened and EBITDA add-backs are prolific and sizable. As of August 2021, around one-third of all outstanding leveraged loans are of lower quality, with that proportion being even higher at nearly 50% for issuers with less than $1 billion of funded debt.

This combination of high growth and weak underwriting has created adverse side effects, which can be particularly pernicious considering a backdrop of aggressive valuations and historically tight spreads. During previous periods of market dislocation, the leveraged loan market has shown meaningful vulnerability largely due to the structural constraints of the market’s largest buyer base – CLOs. While the tranched CLO structures themselves have proven to be largely resilient during periods of economic turmoil, CLO managers typically manage the underlying pool of loans in their vehicles to maintain a certain level of portfolio quality and limit the number of riskier loans.

Dislocations to issuers typically cause ratings agencies to review the financial health of the issuer and its sector, often resulting in a downgrade of the issuer and/or the underlying tranches of loans. When there is a wave of ratings downgrades during a period of volatility, the primary buyers of leveraged loans often turn into sellers of lower-quality loans in an attempt to remain compliant with CLO portfolio quality metrics. In addition, CLO managers’ ability to support stressed or distressed companies they are invested in can be limited. If CLO managers do participate in company restructurings, they usually receive little to no credit within the CLO structures for non-debt post-reorganized securities that typically comprise consideration in exchange for being the fulcrum security – e.g., equity, warrants, or preferred securities, all of which are often illiquid. As a result, CLO managers may not be able to be patient or await a company’s turnaround and recovery before having to exit a position.

Niche opportunity in private middle market loans

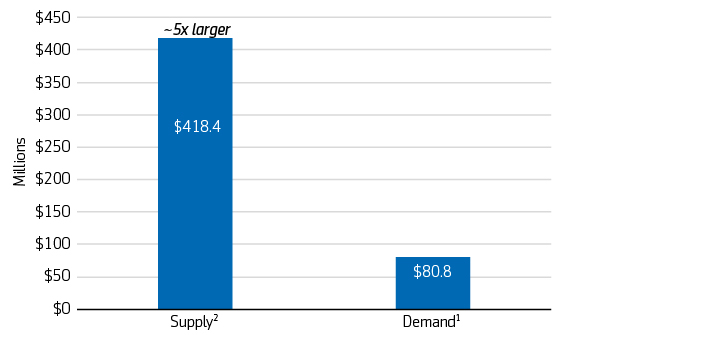

The natural buyer base for this type of stressed or distressed risk in times of volatility is normally comprised of opportunistic, special situations, or distressed credit funds. However, we believe the amount of such capital meaningfully falls short of the opportunity set of secured loans of private middle market companies reliant on the leveraged loan market for financing.

Based on Aegon AM’s analysis of the Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan Index as of July 2021, within the leveraged loan market, there are roughly 800 private issuers with less than $1 billion of enterprise value that have issued approximately $418 billion in loans out of the nearly $1.3 trillion of leveraged loans outstanding. In contrast, based on Aegon AM’s analysis of Preqin data as of July 2021, we believe the amount of opportunistic, special situations or distressed drawdown capital raised in the past five years that is likely to focus on these private middle market issuers comprises roughly $81 billion (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Supply and demand imbalance within private middle market loans

For illustrative purposes.

Source: Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan Index; Preqin; Aegon AM analysis.

1Funds less than $1.5 billion in size raised from 2016 through July 2021 focused on distressed debt and/or special situations in North America.

2Private issuers with less than $1 billion of enterprise value (using funded debt as a proxy for enterprise value).

Barriers to entry create potential opportunities

We believe this private middle market segment is overlooked for several reasons:

- Illiquidity: Loans of middle market issuers have typically traded 200 bps wider on average than larger companies, per S&P/LSTA data over the period of 2011 – 2020, reflecting an illiquidity premium. Given that illiquidity, it can be tough to source meaningful positions..

- Difficult to get information: Many middle market loan issuers are private companies that are often challenging to conduct diligence on due to sparse public or sell-side research, gated data site access by private equity sponsors to opportunistic, special situations, or distressed funds, particularly during periods of dislocation, and limited access to management teams.

- Too big for some, too small for others: It is our experience that larger opportunistic, special situations, or distressed fund managers tend to focus on investments in larger capital structures, often with a distressed-for-control mandate and with a need to put significant capital to work. For smaller such fund managers, it can be challenging to have or develop the scale, relationships, and experience required to identify, source/trade and underwrite attractive opportunities in this space. For example, the debt of middle market companies is typically traded by smaller broker/dealers, is often less broadly syndicated, or is held within BDCs or sometimes co-investment structured product vehicles.

Taken altogether, the barriers to entry are fairly high in order to be a prepared liquidity provider to private middle market issuers during periods of dislocation. Experience, scale, trading relationships, and infrastructure are required to know which secured loans trading at discounts are attractive and also be able to capitalize accordingly or provide capital structure solutions proactively.

Pursuing the supply/demand imbalance

As performing levered credit asset classes have grown, so has the amount of opportunistic capital to serve as the incremental buyer when dislocations occur. However, the market dynamic within the distressed and special situations space can be characterized as highly competitive and partially commoditized, with a proliferation of information and advisory services catering to the industry. As such, capital raised in the space has generally been allocated toward large, well-established fund managers who typically invest in larger, more liquid situations, while investors seeking yield elsewhere in credit have gravitated toward private credit.

Notwithstanding the broader dynamic within opportunistic levered credit, we believe a sizable pocket of private middle market loans with an attractive supply/demand imbalance remains. However, given the challenges in knowing this space well, not every opportunistic manager will have an edge in pursuing this imbalance during periods of dislocation.

From an investor’s perspective, we believe it is prudent to identify and allocate capital to fund managers ahead of a potential dislocation rather than waiting for fault lines to materialize in financial markets. The obvious question is – which managers are likely to benefit most from information asymmetries and with barriers to entry still prevalent within private middle market loans?

In our view, those managers who have a significant head start on diligence and underwriting in this space, who are nimble yet scale, who have a strong track record investing in dislocated credit, and who are able to deploy capital quickly will likely be best positioned to take advantage of the aforementioned market inefficiencies and generate compelling returns during a levered credit market dislocation in the upcoming years.