Portfolio manager Denny Fish and analyst Shaon Baqui posit that semiconductor producers face an uphill battle in meeting rising demand for chips as the digitisation of the global economy accelerates.

Key takeaways

- Low inventory levels and a hunger for chips have resulted in a historical supply/demand imbalance for the semiconductor industry.

- Given the increasingly important role played by semiconductors in a rapidly digitising global economy, the shortfall’s knock-on effects will have far-reaching implications.

- How management teams across industries navigate the chip shortage will likely influence their near- to mid-term revenue and earnings profiles.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about many economic dislocations. One that has received considerable attention is the global shortage of semiconductor chips. This development is often framed within the context of the automotive industry and the knock-on effects of idled assembly lines and skyrocketing used car prices. But the chip shortage and the tribulations caused by it spread much wider, impacting all industry sectors, regions and likely a sizeable share of the world’s households.

Really bad timing

The semiconductor industry has been notorious for persistent imbalances as chip producers and consumers try to find an equilibrium between supply and demand. A historically fragmented industry structure typically exacerbated the problem. The current – historic – imbalance is the result of the collision of two forces, both directly related to the pandemic: supply chain disruptions caused by economic shutdowns occurred at the same time the world’s hunger for chips exploded as the pandemic accelerated the digitisation of the global economy.

In a typical cycle, the semiconductor industry increases capacity to meet its order books as demand returns. The challenge presently facing manufacturers is that the slope of the demand curve has steepened during the pandemic, meaning chip makers are scrambling to reach an increasingly higher target. In the shortage’s early innings, industry executives expected inventories to be rebuilt by the end of this year. As the magnitude of the imbalance has come into sharper focus, optimistic estimates call for mid-2022, and more cautious voices fear it won’t fully subside until perhaps early 2023.

Given the complexity of semiconductor fabrication, additional capacity cannot simply sprout up. Since demand continues to outpace supply – and there are no major greenfield facilities coming online until late 2022 – we share the concern that the market for chips will become even tighter in coming months. In the interim, management teams across a host of industries face tough decisions about production prioritisation that stand to impact their revenue streams and profitability. When viewed from this perspective, further developments surrounding the chip shortage should merit the attention of all investors.

Two years in the making

To understand how the situation reached this point, we must revisit 2018. During that year – and typical of a normal semiconductor cycle – the industry built up inventory in anticipation of late-year demand, which ultimately did not materialise. Entering 2019, as chipmakers were still culling stockpiles, the US-China trade war cast a shadow on global growth expectations, further crimping demand as neither producers nor buyers wanted to hold excess inventory.

The arrival of the global pandemic had the unique consequence of further quashing demand in some semiconductor end markets while catalysing it in others. The automotive sector was the most notorious example of the former as buyers cancelled orders, while anything associated with remote work and the digitisation of the global economy – cloud computing, laptops, gaming consoles and Wi-Fi routers – exemplified the latter.

By the time demand returned for cars and other products used outside the home, the order books of raw materials providers and chip foundries were already full. To make matters worse, a series of idiosyncratic disruptions along the supply chain further hindered capacity. The stark reality is that it took two years for the semi ecosystem to slip into such a deficit and it may take almost that long for it to claw itself out.

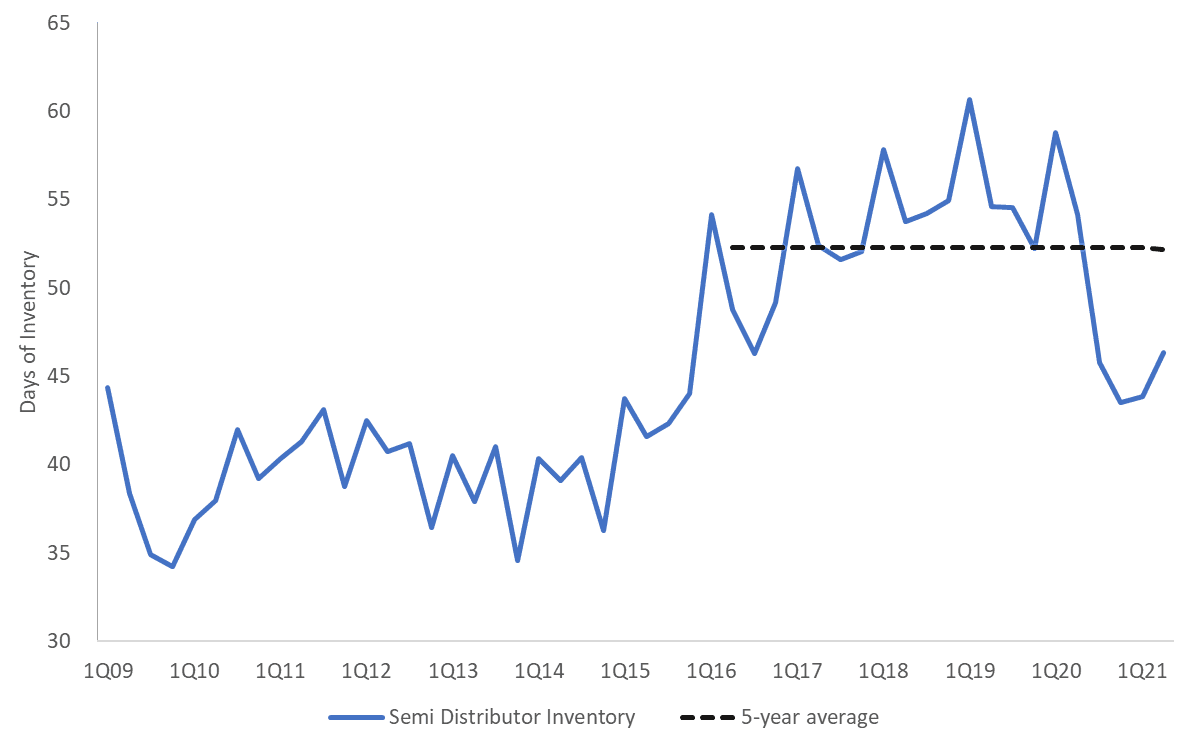

Semiconductor distributor days of inventory

A confluence of factors has resulted in the industry unable to meet skyrocketing chip demand in the wake of commercial activity rebounding and the digitisation of the global economy accelerating.

It is different this time

A convergence of factors has led us to conclude that the current chip imbalance won’t be resolved as easily as in earlier cycles. Foremost, the demand for semiconductors has hit an inflection point and, in our view, there is no going back as an increasing share of global economic activity occurs digitally. Remote work has created incredible demand for the complex chips that power cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI) and developments with the world’s automotive fleet, including advanced driver assistance systems and vehicle electrification. Case in point: an electric vehicle can contain up to five times the semiconductor content than cars with internal combustion engines.

The automotive industry is also a major consumer of analogue chips, as are a range of products and applications associated with the Internet of Things (IoT). This market segment, which includes microcontrollers and sensors, is an area that we believe could remain under acute stress as demand for analogue chips becomes even more ubiquitous.

While the semiconductor industry scrambles to meet rising demand, it must also navigate tectonic shifts in the geopolitical and global trading environment. The chip supply chain is among the most globalised and the move toward localisation and countries’ desire to control end-to-end production will likely have far-reaching ramifications as chip producers adapt to a potentially more fragmented and siloed marketplace.

Lastly, although much of the attention has been placed on end users such as autos and IoT devices, some investors may not fully recognise the risk posed by the prevalence of analogue chips in the machinery and tools of the world’s factory floors. In a worse-case scenario, if an assembly line is dependent on a series of four-dollar chips, and a few go down with no replacements in stock, production may grind to a halt, resulting in shortages of products with seemingly no relation to the semiconductor complex.

An investor’s perspective

The chip shortage is neither an annoyance nor a sideshow. Investors across asset classes and sectors need to realise that a 21st century economy cannot operate without semiconductors. On the supply side, we believe the current imbalance will create even more tailwinds for the semiconductor capital equipment makers that enable chip production. Should markets become more localised, the number of buyers for this complex machinery will likely grow.

While we are mindful of near-term perturbations surrounding supply and demand, we believe the hunger for analogue chips will continue to grow as digitisation results in ever higher levels of semiconductor content across a broad range of applications. Finally, we believe secular demand for the processors, accelerators, and networking chips that power AI and cloud computing services will continue to strengthen in the years to come as the world moves toward a digital economy.

Management decisions must also be revisited as the practice of just-in-time inventory on the part of chip buyers exacerbated the current shortage. Consequently, companies especially dependent upon chips in their end products or production processes may need to consider transitioning to a “just-in-case” inventory method. To counter the risk of over ordering chips by a magnitude of four or five with the hope of cancelling shipments should demand not materialise, chip producers are increasingly requiring orders to be non-cancellable.

The semiconductor shortage has proven to be a high-profile pain point for the global economy, and it shows little sign of abating. While the nuances of the industry structure and semiconductor cycle are typically the domain of tech investors, the global economy’s increasing dependence upon the complex functionality of cloud- and AI-enabling chips as well as process-oriented analogue chips, means that further industry developments should command the attention of all financial market participants.

Footnotes:

Idiosyncratic risks: factors that are specific to a particular company and have little or no correlation with market risk.

Greenfield facilities: a company building its own, brand new facilities from the ground up.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. Any securities, funds, sectors and indices mentioned within this article do not constitute or form part of any offer or solicitation to buy or sell them.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.