The additionality and environmental credentials of each issuance must be scrutinised.

Limiting climate change and addressing the world’s other great environmental challenges, including biodiversity loss, will require immense vision and investment. Companies and governments must mobilise vast sums to fund the investments needed to align themselves with net zero targets, mitigate their environmental impact and adapt to emerging environmental risks.

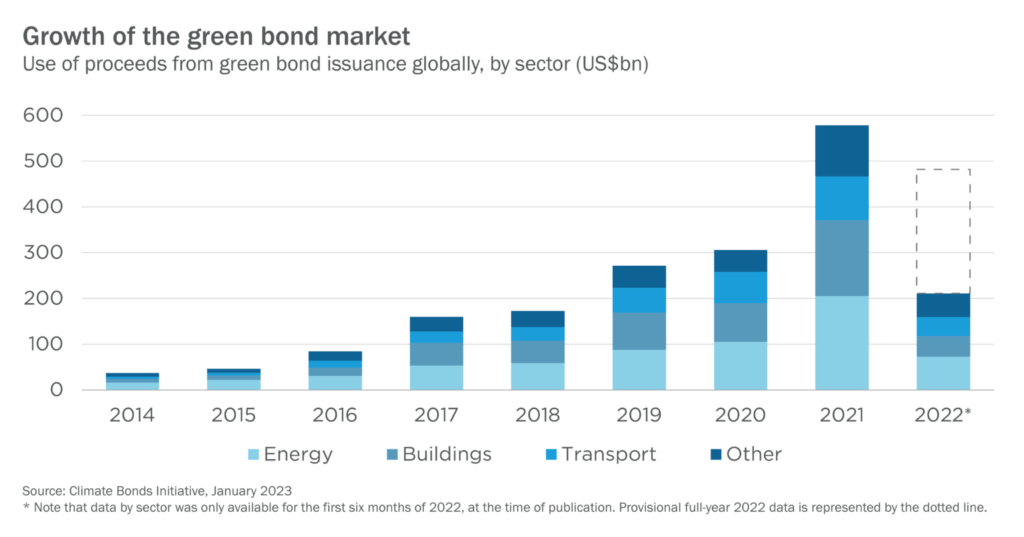

Green bonds, where issuers earmark proceeds for climate or environmental projects, will be key. The Climate Bonds Initiative has estimated that green bond issuance must reach at least US$5tn a year by 2025 “to make a substantive contribution to addressing” climate-related risks. To put this in context, barely more than US$2tn had been issued in total by the end of 2022.

Yet the trajectory has been upward. Although green bond issuance in 2022 was slightly lower than in 2021, when more than US$500bn was raised, this was broadly in line with the general decline in bond issuance. Both 2021 and 2022 represented a significant increase from earlier years.1

Borrowers are naturally keen to tap into robust investor demand. In some cases, though, the terms of issuance stretch definitions of a green bond. This poses a threat to the integrity of labelled bonds, especially in the current context of widespread greenwashing accusations.

Deciphering more shades of green

The lines have become more blurred as labelled bond issuance has broadened and become more nuanced. In the past, we would typically have seen use-of-proceeds bonds going towards financing projects that are clearly transition-related, like new renewable energy assets.

As green bond issuance has targeted a wider range of activities, we have seen it become relatively common for issuers to exercise latitude and label bonds as green when proceeds are being used to fund, or partially fund, business-as-usual activities. The reality is that there are therefore many shades of green.

To layer complexity onto nuance, issuances that have limited additional positive impact, or additionality, are often verified by second party opinion as aligned with International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) green bond principles. These issues typically provide exposure to a portion of a business or sector, while reducing exposure to other activities.

Some industries can be particularly prone to contention when it comes to green bonds. Take the rail industry, for instance, which is responsible for the vast majority of coal transportation to its final destination in the US, but is also highly efficient versus road transport. The proceeds from a recent green financing issuance we invested in are primarily to finance the acquisition and improvement of railcar fleets that are leased to customers in a variety of industries, while limiting exposure to railcars that transport fossil fuels.

Green bond frameworks generally exclude railcars that transport fossil fuels. However, the issuing company in this instance assured investors that eligible assets accounted for at least three-quarters of its railcar portfolio. From our perspective, the issuance delivered the additional environmental benefit that we look for by enabling lower carbon emissions related to the transportation of goods, increased fuel efficiency and reduced highway pollution and congestion.

Checking for additionality

Alongside our rigorous analysis of the financial case for investing in bonds that are labelled as green, we look at them issuance by issuance and apply a seven-point checklist to ensure they deliver the additionality that we look for.

First, we consider whether the bond issuer meets our sustainability criteria. We may invest in a lower ESG-rated issuer if they have a clear transition path.

Second, we consider whether the issuance meets ICMA Green Bond Principles. This is not essential, and is not in itself any guarantee of impact, but it does serve as an initial check in our due diligence process.

Third, we analyse whether the issuance will deliver true environmental impact by looking at where proceeds will be used. Is there additionality or will they merely finance business-as-usual activities?

Fourth, we look at the timeline for distributing the proceeds of an issuance. We expect there to be a clearly defined and prompt use of the capital raised.

Fifth, we check for provisions in the event of any change in the use of proceeds or if the bond does not achieve its goal, perhaps because projects are ultimately unsuccessful.

Sixth, we seek out short look-back periods with recent baselines for comparison.

Finally, we expect impact measurement to be clearly reported at least annually.

Digging into the detail of each bond

Looking ahead, the tightening of regulatory standards in the EU should drive higher standards of reporting on green bond issuances, including beyond the bloc. We expect borrowers in the US and elsewhere to voluntarily comply with this de facto regulatory gold standard to ensure access to global capital.

While this should reduce the scope for ambitious claims to be made by issuers of green bonds, as active fixed income investors, we expect to remain busy digging into the detail of every issuance and weeding out those bonds that are not quite as green as they purport to be.

1 Climate Bonds Initiative, 2022 data correct as at 13 January 2023, subject to adjustment