Markets appear to be breathing a sigh of relief after several weeks of turmoil in the US and European banking sectors which brought back unpleasant memories of the early days of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

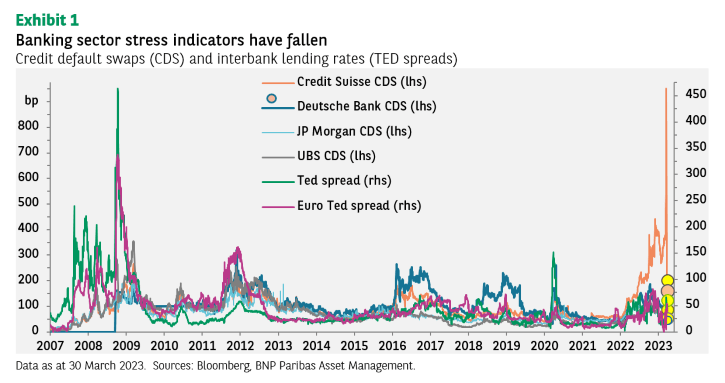

The reality is that credit default swaps and Treasury-Eurodollar (TED) spreads, which measure interbank lending rates, never rose particularly high (with the obvious exception of those related to Credit Suisse) and have moderated since (see Exhibit 1).

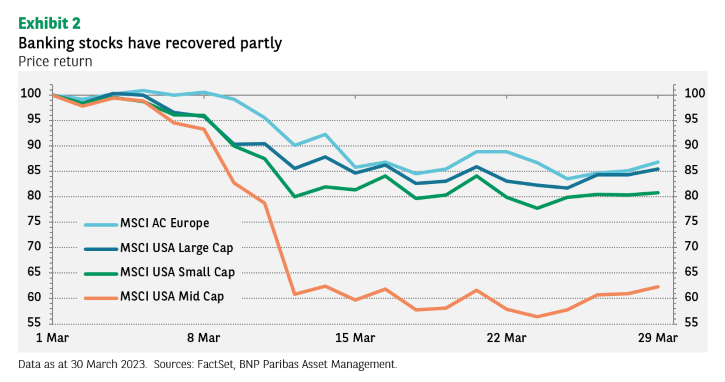

Banking sector stock prices have recovered modestly, but are still showing the effects of the turmoil. The MSCI AC Europe Banks index remains down by 13% from the beginning of March, and the USA Mid Cap Banks index has plummeted by almost 40% over the month (see Exhibit 2).

Sticky or fluid deposits?

We will have to see whether the recent deposit flight from smaller US banks continues. The most recent data (week ending 15 March) showed a 2.2% decline in deposits. About half of the money seems to have been deposited with larger banks, with the other half invested in money market funds.

Nonetheless, we believe the recent problems do not represent a systemic risk. While there are concerns about bank asset-liability management and interest-rate risk hedging in the US banking system, this is not 2008 and US Treasuries are not mortgage-backed securities.

That is not to say that there will be no more market turmoil ahead. The sharp increase in interest rates and the reduction in liquidity we have seen over the last year was inevitably going to cause stress. Arguably, last year’s turmoil in the UK liability-driven investment (LDI) market and declines in crypto currencies were early signs.

Even if markets are anticipating that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) will cut interest rates soon (a view we disagree with), the full impact of the rate rises we have had already has yet to be felt. It is worth recalling that the total debt/equity ratio for US and European corporates is 8-11 percentage points higher now than it was before the GFC. Even if that debt was raised at a lower interest rate, it will need to be refinanced at higher rates in the future – and potentially in an environment of slower growth.

Lower central bank peak rates

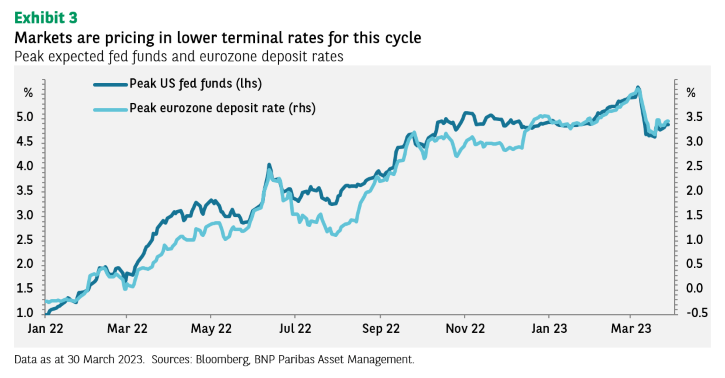

The market now expects the Fed and the European Central Bank’s peak policy rates in this cycle to be about 75bp lower than was the case at the beginning of the month (see Exhibit 3).

Indeed, it is likely that the central banks will not need to raise rates by as much as previously anticipated due to the negative impact on growth from the banking sector turmoil. Credit growth was already slowing in the US and eurozone, and lending standards were tightening.

Increased regulatory scrutiny and the need for many banks to shore up their balance sheets means this trend will likely continue, reducing overall economic growth and hence inflation.

How big that impact will be is difficult to predict. Analysis of historical episodes shows a wide range of possible outcomes. We doubt it will be a heavy enough impact to lead to a swift deceleration in inflation.

We expect upcoming labour market and inflation data to be strong again. If it is, markets will likely worry once again that central banks will need to keep rates higher for longer to weaken it.

This is particularly the case in the eurozone where core inflation is still rising. Ultimately, a recession may be necessary to squeeze the inflation genie back into the bottle.

Disclaimer

![]()