Markets suggest the US has almost reached an inflection point, while the UK and Europe have further to go in their battles against inflation.

Prospects for the global economy are mixed, at best, this year: While the US should follow the UK and Europe into recession, we expect China to bounce back after scrapping its zero-COVID policy.

Over the past few years, the global economy overheated. Fiscal and monetary policy support were lavish during the pandemic, pushing up demand. But supply was reduced – both in labour markets (due to early retirement, reduced migration, school closures and self-isolation) and energy markets, particularly following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

This resulted in excessive inflation and, in turn, aggressive monetary tightening. With commercial banks beginning to tighten credit availability, we appear set for recession. Official US GDP data have been volatile, but the underlying details and survey data point to a loss of momentum. The housing market is dropping, consumers are burning through their excess savings and corporate fundamentals are deteriorating.

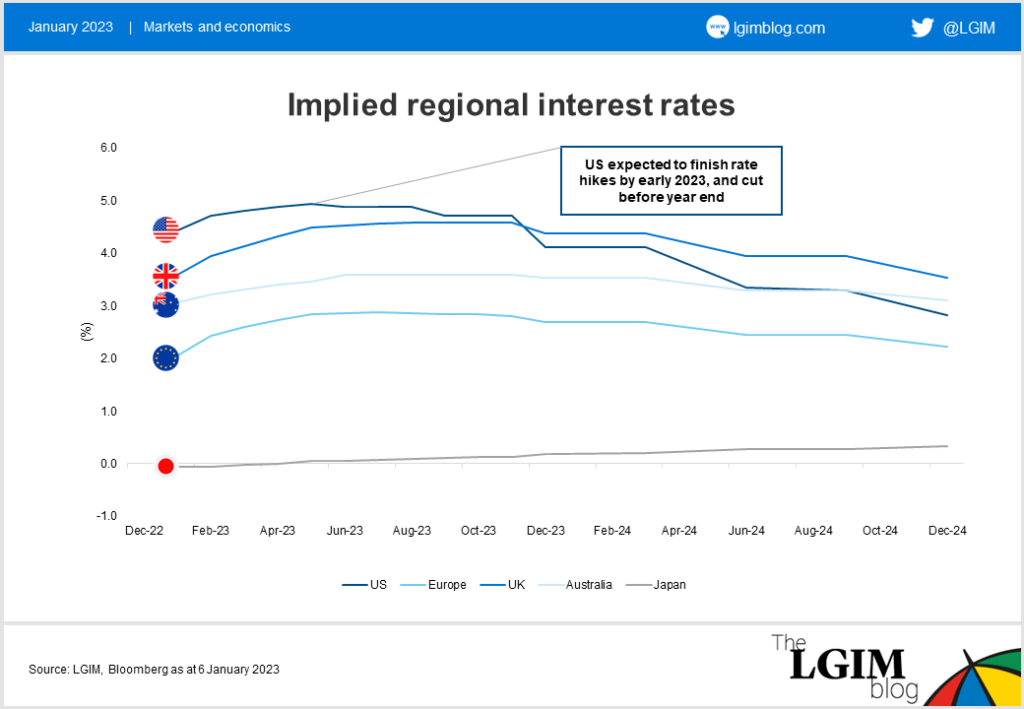

Given elevated job vacancies, there is considerable uncertainty as to how long it will take for unemployment to rise. However, we expect recession to begin in the spring and for output to fall throughout the rest of 2023. Unlike last year, market participants are close to pricing in enough additional hikes for the Fed; we also see the prospect for rate cuts towards the end of the year.

Sticky inflation

The situation is worse in Europe and the UK, where the energy supply shock is most acute and worse than similar crises experienced in the 1970s. Not only are real incomes being squeezed, but central banks are also tightening forcefully to limit second-round effects.

The UK has also suffered from policy blunders. These have resulted in market pressure forcing the government to deliver tighter fiscal policy than would have otherwise been necessary.

More positively, a mild winter has dampened the energy price shock, though the outlook remains uncertain. Another welcome development is that supply-chain disruptions – which led to a surge in goods price inflation in 2022 – are rapidly improving, aided by cooling demand.

Service-sector inflation will likely prove much stickier, in our view, but recession and rising unemployment should reduce wage pressures as the year unfolds. The extent of rate cuts by central banks later this year and into 2024 will likely hinge on whether core inflation can make it all the way back to target or if it settles at a still somewhat uncomfortable level.

Meanwhile, the outlook for China is much better following the abandonment of its zero-COVID policy. The economy suffered a significant setback in the last quarter of 2022, but we expect a rapid rebound this quarter as its COVID wave peaks. Recent

policy initiatives for the property sector also seem to be a gamechanger. These should allow the property market to bounce back to health, without triggering another unsustainable boom.